Diversity & Inclusion’s Learn More Series: Renowned Disability Rights Leader Judy Heumann to Speak

Judith Heumann, an internationally recognized lifelong advocate for the rights of disabled people, is the inaugural keynote speaker in BU Diversity & Inclusion’s 2021 Learn More Series, which this year focuses on disability. The virtual event begins at noon over Zoom. Photo courtesy of Judith Heumann

2021 Diversity & Inclusion’s Learn More Series Focuses on Disability and Impact of Ableism

Renowned disability rights leader Judy Heumann to speak today

Curb cutouts. Closed captioning. The right to accommodations at work, school, and all other areas of public life. Thanks to the lifelong advocacy work of Judith Heumann, these standards of accessibility, and the civil rights of any person who is or will become disabled, are protected under US federal law.

Heumann—who was instrumental in the creation and passage of landmark legislation such as Section 504 (of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973), the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—is the inaugural keynote speaker for this year’s BU Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) Learn More Series. Each year, the series focuses on a single topic of social importance through discussions and other programs; this year’s focus is on disability and the impact of ableism.

Heumann will participate in a virtual fireside chat today, Tuesday, September 14, titled “Signs of Resistance: Disability Cultural History.” She will be joined by Swati Rani, a College of Arts & Sciences Writing Program lecturer and a leadership board member of Staff and Faculty Extend Boston University Disability Support (SAFEBUDS). Heumann will discuss her trailblazing activism and vision for more inclusive higher education.

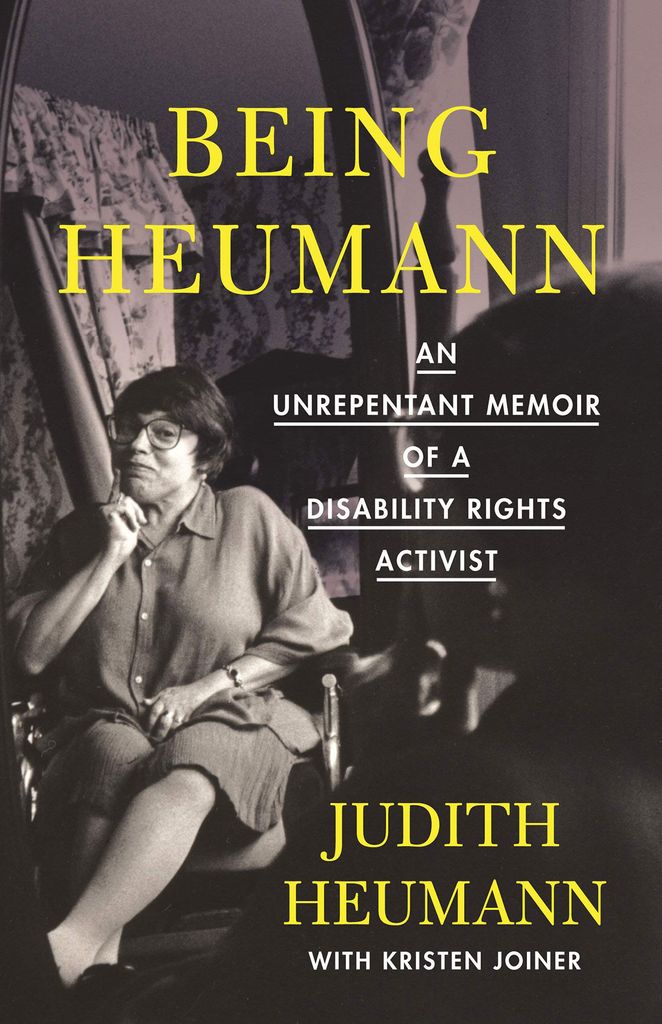

Heuman’s recent memoir, Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist (Beacon Press, 2020), captures her early life in Brooklyn, N.Y., after she contracted polio and began using a wheelchair for mobility. A founding member of the Berkeley Center for Independent Living (the first of its kind in the country), she had a pivotal role in organizing the San Francisco 504 Sit-in of 1977, as seen in the Netflix documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution. A watershed event, 150 people with disabilities and allies occupied a federal building for 25 days, until Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the first piece of civil rights legislation ensuring rights for people with disabilities, was signed into law. Heumann went on to cofound the World Institute on Disability in 1983, which works to advance the rights and opportunities of disabled people globally. She served in both the Clinton (1993-2001) and Obama (2010-2017) administrations, and traveled across the globe in her motorized wheelchair as the World Bank’s first advisor on disability and development.

“Diversity, equity, and inclusion is not just about race, class, and gender,” says Karin Firoza, BU D&I director of special projects. “It’s also about folks with disabilities and disability as an identity—that often gets lost in the conversation. We want to explore disability beyond a medical diagnosis, and celebrate and acknowledge the cultural identity of folks with disabilities.” The theme had been chosen in advance, Firoza says, but it’s proven a prescient choice given the introduction of the RISE Act in the Senate this past summer, which would remove significant financial barriers for students with disabilities pursuing a postsecondary education.

In addition to Heumann’s talk, the series will also cover the history of the treatment of people with intellectual disabilities, disability representation in the arts, and disability justice and allyship. Other notable speakers: Haben Girma, a human rights lawyer and the first Deafblind person to graduate from Harvard Law School, disabled writer and author Amanda Leduc, and comedian Kristina Wong.

BU Today spoke with Heumann in advance of today’s event about disability identity, the impact of the documentary Crip Camp, and the future of disability advocacy.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Q&A

With Judith Heumann

BU Today: Most people are familiar with the word ‘disability,’ but fewer recognize that disability is also an identity and culture. What is disability identity and culture and when did they emerge?

Judith Heumann: I wouldn’t say they’ve emerged, I would say they’re emerging.

You know, culture is something which takes decades, centuries, to really emerge. And one of the big issues going on within the disability community is that from a statistical perspective, ADA perspective, and 504 perspective, there are specific [guidelines] about who is defined as having a disability. For the purposes of discrimination or benefits, you may or may not be eligible. But that’s not an issue of culture.

Over the last 50 or 60 years, there has been a growing evolution of dispersed disabled people feeling the need to come together, and not in an artificial way. And by that, I mean: when I started going to school—or didn’t start going to school—I was not allowed into school, because I had a disability, and I was considered to be a fire hazard. And then, the next choice I was given was to only go to classes with disabled children. And then eventually, I was able to be in classes with nondisabled children. The construct of going to classes with disabled people was a forced construct. It wasn’t intended to help disabled people see themselves as having a similar identity and culture that we may be evolving into, like in arts or history. In the US and around the world, people with disabilities recognized the need for us to come together, and the initial need [was] to develop laws: antidiscrimination laws, affirmative action laws, laws that protect the rights of disabled people.

Over the last number of decades, we’ve also broken out of the individual silos of disability classification, meaning: polio, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, lupus, etc. We’ve been recognizing that there are common areas of discrimination, and common visions of what we want to be able to do. And as we’ve been doing more of this, we’ve also recognized common areas of interest, like the ability to express ourselves in poetry, the arts, music, sports, or whatever it may be. I think there’s a growing set of avenues that are allowing us, and then the broader society, to really look at what we mean when we’re talking about disability culture, or the value of bringing our voices together with a similar story.

So I think we are an emerging community, we are an emerging culture.

BU Today: You write in your memoir: “It wasn’t an I, it was a we.” Why did you frame it this way, and how do you see your story within the broader history of disabled people in the United States?

Judith Heumann: It’s a great question. I mean, there are no movements of “I.” A movement, by definition, is more than one person. And I think that’s what’s very important about the disability movement: it is the coming together of more people who have a similar vision. It’s about the oppression that they’re experiencing—whether or not they use that word. And so, “the we” is very important to me, and we [should] continue to highlight all the people who are speaking up and speaking out and making a difference in a little way or a big way, because each person’s contribution is important.

At [Camp] Jened [a summer camp for disabled people in New York state that became a springboard for the disability rights movement], and other camps for disabled kids, we weren’t necessarily freely choosing to go to these segregated camps… [But] being in these camps and in some ways, these segregated [school] programs, we began to look at the expectations that people had for nondisabled people versus the expectations that people did not have for disabled people. We really began looking at the issue of what to do about it: to organize, to no longer feel ashamed about who we are, how we look and how we sound, how we think, how we process, how we interact in society.

We moved away from the negative, [and came] together and reinforced each other. [We] recognize our values as individual people, but also recognize that coming together under the term disability or disabled is very important, because it allows us to stand out. It doesn’t mean that our total being is that of having a disability—which is another very important issue to be looking at. But [coming together] meant [enabling] a growing number of people to throw off the shackles of oppression.

BU Today: The Oscar-winning documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution that you were featured in is a different form of advocacy than policy work. What kind of impact did you hope the film would have, and how do you see the documentary as a tool for advocacy?

Judith Heumann: Crip Camp is a good learning show. It [helps] people not only learn a portion of the story of the disability rights community and about a growing movement, but it’s also enabling people to ask questions like, “How did we organize?” You can see it very clearly in the film: everybody’s voice mattered, whether or not they had typical speech. That is a very important message. Now, the question is, when an individual person is in a group with someone who doesn’t have typical speech, will this film have an impact on them? Will this film let them relax, and take the patience to listen, or to ask questions: “I didn’t understand that, can you say that again?”

One of the reasons why I think that the growth and emergence of a disability culture is very important is because culture is something that people can share. You can share Crip Camp… It’s a way of learning about our stories, and learning about our cultures. Crip Camp, and many of these other artistic representations of who we are, are also very important for us, because most disabled people don’t know anything about this history. If you’re in a family where you’re the only disabled person, there’s nobody else with family that knows the culture. They’re looking at disability as a medical issue.

I think that’s another very important part about what is continuing to evolve [in the disability community]: more people are talking about the need to see ourselves.

BU Today: You’ve spent your life working to ensure that the rights of people with disabilities are protected under US law. How has the fight changed?

Judith Heumann: Well, I’m excited about the fact that there is more organizing going on. There are more disabled people who are involved in more and more aspects of life, whether or not they identify… People are [still] afraid of disclosing; they’re afraid that if it’s known that they have something that is invisible, or even visible, that it can hold them back or deny them hiring or promotion or other opportunities. One of the big topics that is being discussed more is: what are we, as a society, and then as a government, corporation, nonprofit, or religious institution, doing that may be curtailing someone’s ability to bring their whole self to whatever it is? And if we’re fearful of discussing things, then that means we haven’t achieved our objective at all.

We have not made the advances that I would have hoped we would have made given the number of laws that we have in place. I feel that COVID is an example of what we haven’t learned—and I’m not even talking about the issue of people not being willing to be vaccinated. When we look at the types of people who have died as a result of COVID, you have disproportionate numbers of people living in restricted living environments, whether they’re nursing homes, veterans communities, congregate living settings for people with developmental disabilities, etc. In so many cases, these deaths are preventable if people were not living in these congregate settings. But they’re living in the congregate settings because we haven’t invested—not just money, but definitely money is part of it—in the right and dignity of a disabled person to be able to live in the community. And the people who are working with disabled people are not necessarily getting the amount of money that they should be earning. And those jobs are not jobs that are frequently seen as valuable, important jobs. There are many changes that need to be made.

I worry about the effect of global warming, the effect of poverty, of immigration, migration around the world, not just in this country. Disability will continue to increase. We need to be integrating both the issue of prevention, like reducing air pollution, which causes all kinds of lung conditions and others, and the threat of disability. We need to be able to see that disability is not a threat, it’s a reality. And we as a community, whether you have a disability or not, really need to be looking at what we need to do to ensure that people can live a quality life with or without a disability.

BU Diversity & Inclusion’s Learn More Series on disability, featuring Judith Heumann, is today, Tuesday, September 14, from noon to 1:15 pm. Register here to attend virtually. BU D&I will also host a special screening of Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution, on Thursday, September 16, at the GSU Terrace Lounge, 775 Commonwealth Ave., from 2:30 to 4:30 pm . Register for the in-person screening here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.