Reflections on Photographing Trauma

Reflections on Photographing Trauma

A COM lecturer, an alum, and a student on documenting conflict and its aftermath

A 1996 portrait of an African National Congress supporter who was shot in the face and had his home burned the year before. Photo by Greg Marinovich

From distant war zones to protests on US streets, photographers play a vital role in documenting conflict and its aftermath. The best of them can capture layers of drama, trauma, and humanity with the single click of a shutter button. They also risk their physical and mental well-being in pursuit of photographs that can stand as the iconic representations of historic events. Think of Nick Ut’s image of Vietnamese children fleeing a napalm attack, or more recently, Jonathan Bachman’s photo of Ieshia Evans, a lone protestor being swarmed by riot police in Baton Rouge, La. Even in today’s digital, connected world, where everyone is a photographer, the work of professionals devoted to representing conflict and trauma remains vital.

Three members of the College of Communication community—a war photographer, an artist, and a student journalist—discuss their experiences reporting on traumatic events, and share some of the powerful, sometimes disturbing, photos they took.

Seeking a greater truth

Greg Marinovich, a COM master lecturer in journalism, has thought a lot about conflict photography’s power and its pitfalls. He spent years documenting the violence that accompanied South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democratic elections and has himself been shot and injured four times in the field. In 1991, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his photos of African National Congress (ANC) supporters stabbing, stoning, and burning a man to death because they suspected him of being a Zulu spy.

There’s a duality to photography, Marinovich says. “You have these defining moments that are true in the moment—but are they true to the bigger story?”

A good photo challenges the viewer to think—and to learn more.

Ut’s photo, for example, captured the brutality of the Vietnam War. Only when you read about the incident, though, do you learn that the napalm was dropped accidentally on a non-Vietcong village. In early 1990s South Africa, news reports often portrayed violent outbreaks as ethnic clashes, but the truth was far more complex. Investigations later revealed that white authorities and law enforcement not only helped organize attacks, but sometimes participated in blackface. And some perpetrators weren’t Black South Africans, as viewers of a photo might assume, but mercenaries from nearby countries hired to create unrest.

“More complex photography, more ambiguous photography, can lead you to draw your own conclusions,” Marinovich says. “I prefer that. I think being certain of facts and truth and what’s happening just means you don’t know enough.” That is to say, a good photo challenges the viewer to think—and to learn more.

In 1996, Marinovich shot a simple portrait of a young man gazing into the lens. One cheek, bisected by a jagged scar, is turned slightly toward the camera. A dark, blurry background reveals no clues. The man’s eyes convey an immediate, haunting message, but the story behind the image includes several layers that require additional context. The man? An ANC supporter. The scar? Left by a bullet. The dark background? The charred remains of his home.

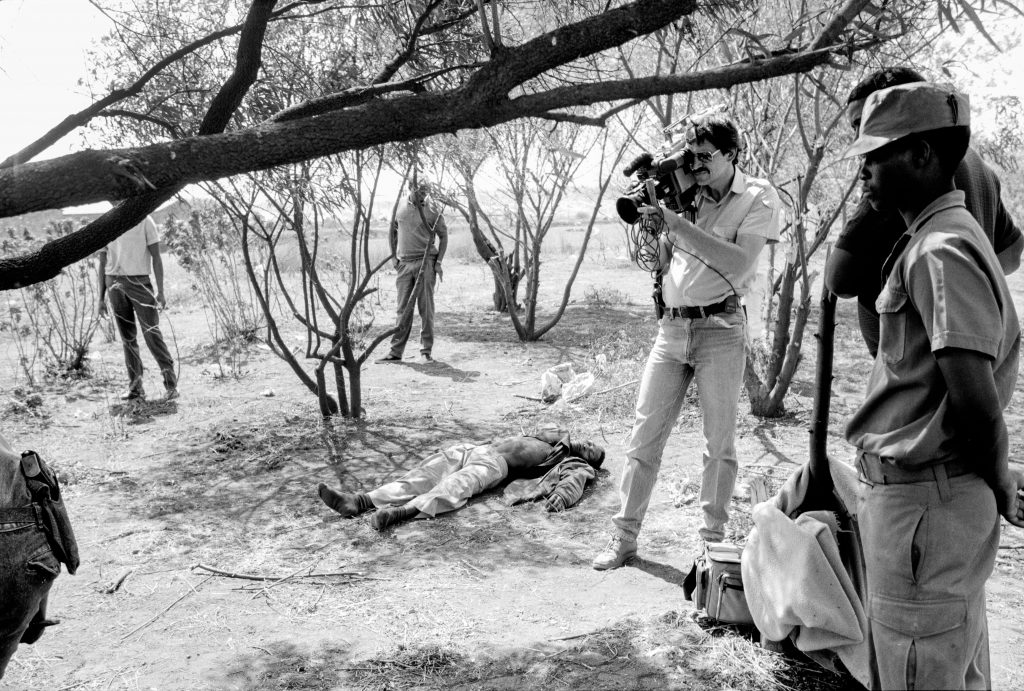

In another of Marinovich’s photos, this one taken in 1990, a group of police officers—including a police cameraman filming something out of the frame—seemingly ignores the focus of the photograph, the corpse of a Black man lying next to them. The image tells an immediate story of violence and abdication of power—but it doesn’t answer many questions. “They’re just ignoring the dead guy,” Marinovich says. “They’re not investigating. They’re documenting it for other reasons—God knows what.”

While a written story can weave events over a span of time, he says, a photo must distill multiple ideas and details into one scene, but that brevity lends photos some of their power. “Photographs are often singular. We can linger on them, in whatever medium they’re in. That helps them to imprint themselves,” says Marinovich, who in 2000 published the memoir The Bang-Bang Club, with longtime collaborator João Silva; their story was later turned into a movie. A good photo, Marinovich says, “represents multiple points of view and multiple angles—and can stand longer than that day as a valid piece of communication.”

Bear witness

Artist Susan J. Barron (COM’80) works in several mediums, from oil on canvas to collage, but for a project about veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she started with photography. Barron was motivated by the number of US veteran suicides—according to the US Department of Veterans Affairs, more than 20 veterans, active-duty, and reserve troops die by suicide each day. “I wanted to shine a light on this epidemic of PTSD and suicide. I wanted to give these veterans a voice,” she says. “I felt that it was a story that I needed to tell.”

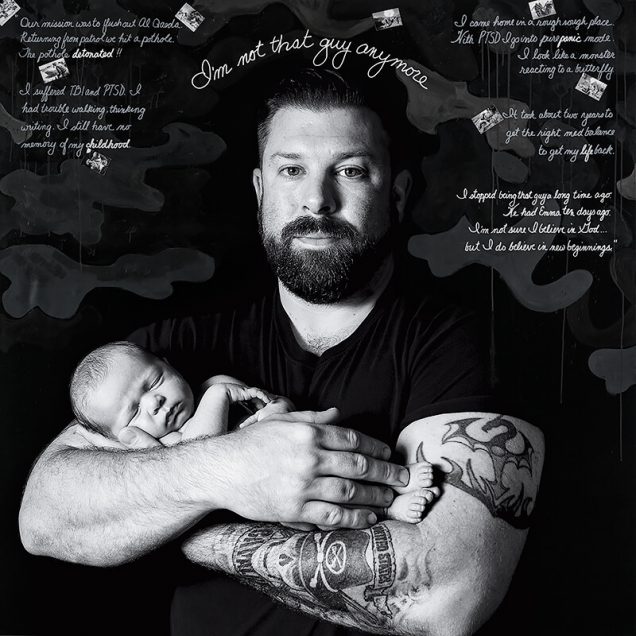

In “Depicting the Invisible,” which is currently on exhibit at the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tenn., Barron combined photographs, paint, collage and text to create 16 mixed-media portraits. Each of her subjects gazes out from the canvas, engaging the viewer. “There’s something that happens when you stare into somebody’s eyes. It’s very difficult to turn away,” Barron says. “If you can’t look away, you have to bear witness.”

Barron layered the veterans’ own words into each portrait. “The elegance of the black-and-white photographic imagery is in direct contrast to the brutality of their stories,” she says. “I was trying to depict the invisible wounds of war—exactly what it is you can’t see—but these works communicate an understanding of what PTSD feels like.”

Unlike journalists reacting to unpredictable events in a war zone, Barron could take her time with each shot. She got to know the vets, speaking with them at length before setting up her first photograph. She photographed them in their homes and garages, the lighting and backdrops carefully controlled. And, once completed, she could present the images as she wanted—choosing the size of the final works (72 inches square) and hanging them in a particular way on gallery walls. “It’s much more introspective, it’s much more controlled, there is a lot of trust in this kind of photography,” Barron says. But, she adds, “When I am creating these works, I am a storyteller. All the Pulitzer Prize–winning photographs that we all have indelibly memorized in our minds—those are also storytelling.”

Though far from a battlefield, Barron couldn’t insulate herself from the emotional risks faced by photographers documenting trauma. As she prepared for the premiere of her exhibition in New York City, she learned that one of her subjects, Damon Ziegler, had died by suicide. “That was really very dark—I felt that I knew him so well and that maybe I should’ve known or could’ve done something,” Barron says. “The other veterans said to me, ‘This is exactly why you’re doing this. This is why we’re doing this with you.’”

Not a typical summer

The Daily Free Press, BU’s student-run newspaper, doesn’t typically publish during the summer. But when Black Lives Matter protesters took to Boston’s streets in June, editor in chief Angela Yang (COM’23) decided to make an exception. “We published almost every day,” she says. “It was a special situation because there was so much going on.”

She and her staff reported on the protests day and night, publishing multiple stories and a series of photo galleries (on May 30, June 2, June 3 and June 5). Images taken by Yang and the newspaper’s photo editor Lauryn Allen (COM’22) showed peaceful protestors carrying signs—”Wake up America” and “Stop Killing Me” read two of them—and also rows of police officers carrying batons, looted stores, and protestors washing tear gas from their eyes.

Nothing Yang had studied prepared her for the scene in downtown Boston, but, she says, she never felt unsafe. Even when she was bumped by a police officer, protestors spoke up on her behalf. On another occasion, a plate glass window exploded as she walked by, likely from a thrown rock or brick. “I didn’t really have time to feel any sort of emotion,” as she navigated the chaotic scene, she says.

Although Yang thinks of herself as a writer first, she also photographed throughout the protests. She says she wanted to avoid focusing on the sensational—tear gas, a burning police car. “It was really important to try to tell as much of the story as possible,” she says. “If we had photos of the destruction of a storefront, we also had photos of people passing out hand sanitizer and boxes of free food for protesters.”

Reflecting on the importance of visually representing conflict and trauma for people not at the scene, Yang repeats a maxim: “When a tragedy happens to more than 200 people, you start to lose the sense that these are people and you see them as a statistic.” A photograph, though, puts a face to the tragedy. “You realize that these are real people that these events happened to. It allows you to empathize,” she says.

A vital role

A lot has changed in photography and media since Marinovich’s time in South Africa. Then, he shot with film and only his best images would be transmitted by the wire services. After they went out, he had very little control over how a published photo was presented. Today, anyone with a smartphone can take, send, and post photos from virtually anywhere. As has recently been the case with videos revealing police brutality, that imagery has the power to spark social movements. It’s a democratization of voice, Marinovich says. “We see things we never saw before. I think that’s quite remarkable.”

Rather than replace the professional photographer, however, Marinovich sees as great an opportunity as ever. “There’s a gap, for people who work in this field to elevate what they do into a realm that makes it stand out—to become the kind of imagery that remains memorable,” he says. “There’s a place for professionalism and I think it’s even more vital than before.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.