Charles Dickens: A Novelist for Our Times

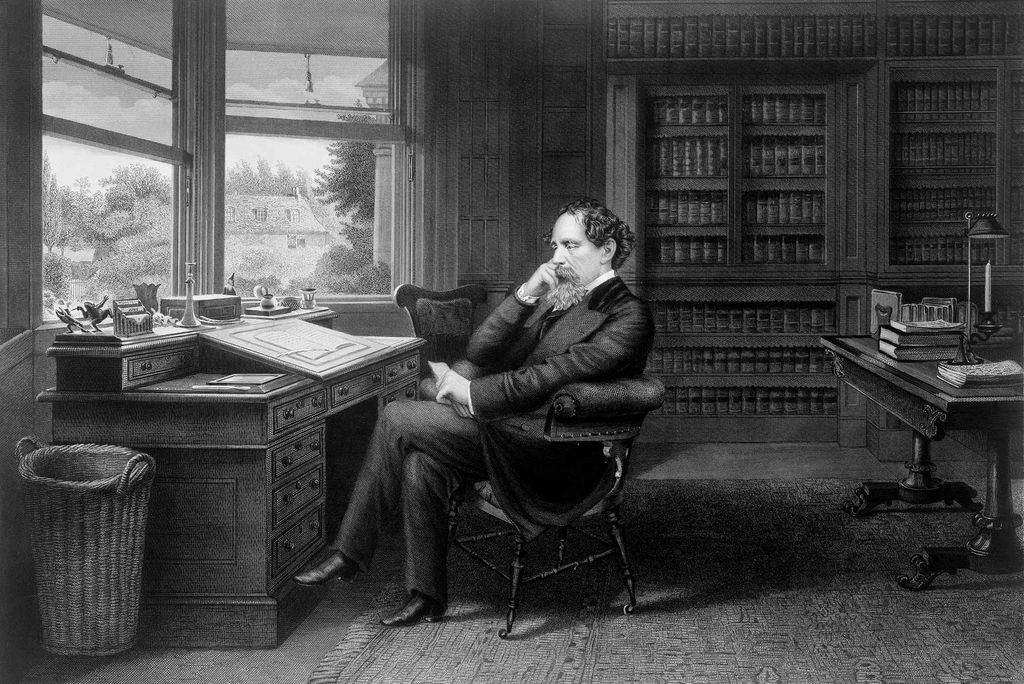

Charles Dickens, photographed in 1867, three years before his death on June 9, 1870. Photo by Jeremiah Gurney

Charles Dickens: A Novelist for Our Times

150 years after his death, author’s themes of poverty and social inequity resonate

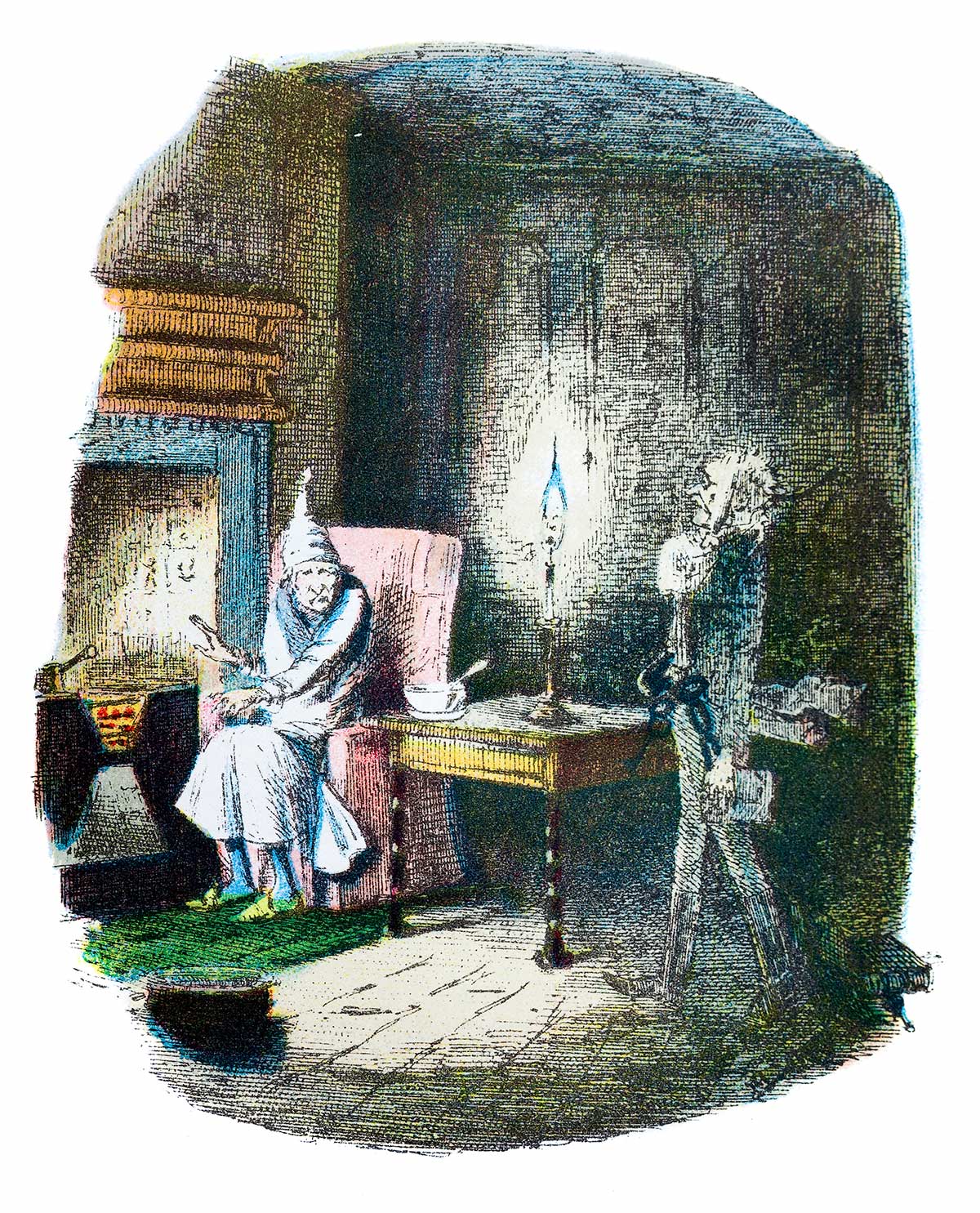

When English novelist Charles Dickens died on June 9, 1870—150 years ago today—he was mourned as a national hero and buried in the Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey. During a career that spanned nearly 40 years, Dickens created some of the most indelible characters in fiction—Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, and Jacob Marley (A Christmas Carol), Pip and Miss Havisham (Great Expectations), David Copperfield, Uriah Heep, and Mr. Micawber (David Copperfield), and Oliver Twist and the Artful Dodger (Oliver Twist).

Renowned for his ability to mix comedy and pathos and to move readers, Dickens was also a pioneering social reformer who fought throughout his life to improve the living and working conditions for the poor.

At the time of his death, he was a literary superstar, celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic. His two speaking tours of America, in 1842 and in 1867 and 1868, drew standing-room-only crowds from Boston to New York, Richmond to St. Louis.

His books have never gone out of print and have been translated into 150 languages. Today, there are more than 400 film and television adaptations of his novels, with more on the way, including a new take on David Copperfield, with Dev Patel as the eponymous lead character.

What accounts for the Victorian novelist’s enduring popularity? We reached out to Dickens scholar Natalie McKnight, dean of the College of General Studies and a professor of humanities. The author of Idiots, Madmen and Other Prisoners in Dickens, she is coeditor of Dickens Studies Annual and president of the Dickens Society, which conducts and supports research into the author’s life and work.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

BU Today: When did you first discover Charles Dickens?

Natalie McKnight: My first taste of Dickens came with the Mister Magoo animated A Christmas Carol when I was four years old. I am happy to say that I had the pleasure of giving a talk on that version at a symposium in Iceland several years ago (not something I ever envisioned when I was working on my PhD).

BU Today: What led you to become a Dickens scholar?

Natalie McKnight: When I was a graduate student at the University of Delaware, I was lucky enough to have Elliot Gilbert as a professor in a Dickens seminar. He occasionally read to us in class, and we’d laugh out loud, cry, shake our heads in amazement. I figured that any writer who could evoke such powerful responses was worth spending a lifetime studying. And I was right.

BU Today: What accounts for Dickens’ ongoing popularity?

Natalie McKnight: Dickens continues to move people—and people want to be moved and need to be moved by characters and situations that are beyond themselves. We need emotional exercise as much as we need physical exercise; the trouble is, we’re proud of the latter, but embarrassed by being moved by others (real or fictional others). But Dickens also makes us think: he has many really illuminating passages when he captures the distorted perceptions of people in altered states of mind, or ones where he dissects how goodness in one person unintentionally brings out cruelty in another. People who really don’t know Dickens well think that his characters are caricatures—and some are, but most are not—and there is as much psychological realism in his works as in those of Victorian novelists who get more credit for that kind of thing because they are more obvious about it. People continue to be moved by his characters, as their tragedies, losses, and heartbreaks are human and universal.

He repeatedly warned of the dangers of sharp divides between the rich and the poor. It’s there in A Tale of Two Cities most obviously, and it’s there in A Christmas Carol, but it’s subtly there in almost all his writings. Nothing good comes from the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, and sometimes a crisis—like the spread of a disease—collapses this dichotomy in ways that highlight the cluelessness of those who think their money can protect them from sickness or death or that they can hoard all the wealth with no negative repercussions.

BU Today: Dickens wrote a lot about disease. What do you think he would have made of our current pandemic?

Natalie McKnight: He would have been all over this—he would probably have written a series of essays with some coauthors for All the Year Round or Household Worlds, two of the journals he edited. He probably would have given speeches about inadequate access to public health services, and the pandemic would have definitely made it into his fiction. And actually, anachronistically, it is in his fiction: there’s a smallpox epidemic in Bleak House, and Little Dorrit starts out with characters in quarantine in Marseilles due to the threat of a plague. He also wrote powerfully about the spread of hysteria being like a disease (something I’m writing about now), and that’s certainly something we’ve seen with reactions to COVID-19, with shoppers madly dashing for toilet paper in supermarkets and mobs of livid protesters pushing for an end to stay-at-home orders.

BU Today: It’s hard to underestimate the kind of celebrity Dickens achieved in his lifetime.

Natalie McKnight: He was the first huge pop-culture celebrity, and he maintained that celebrity for decades. He earned it because he created characters and stories that people cared deeply about, and he wrote serially, so people would be caring about the characters and plot lines over the course of many months. The characters would become part of their lives, and readers couldn’t wait to get the next installment. There’s the famous (and true) story of people standing on the docks in New York City waiting for ships coming in with the next installment of The Old Curiosity Shop, desperate to find out whether Little Nell would live.

BU Today: The Dickens Society had planned to host an international conference in London in July to mark the 150th anniversary of Dickens’ death, but, as president, you had to cancel it because of the COVID-19 pandemic. There’s going to be a virtual conference instead. Can you talk about that?

Natalie McKnight: I’m not organizing this one, but I am participating. It’s called #Dickens150 and it is being held via Zoom on the anniversary of Dickens’ death, June 9, and the proceeds will go to help the Dickens Museum, where we were to have had a reception. Like all museums in this pandemic, the Dickens Museum is really hurting because it’s lost all its revenue for months. So the virtual meeting will help.

BU Today: Finally, perhaps an unfair question to ask of someone who has devoted her research to studying Dickens’ work, but do you have a favorite novel?

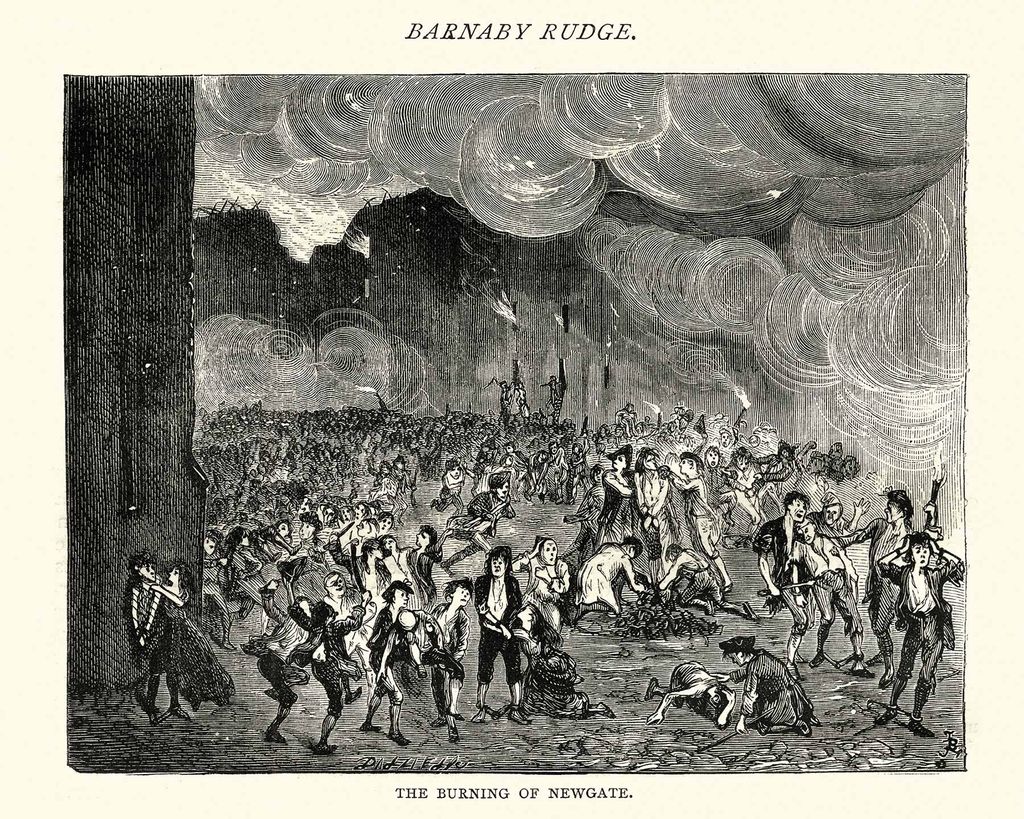

Natalie McKnight: It’s not an unfair question at all. I get asked it all the time. My favorite novel is probably the one that’s read the least: Barnaby Rudge. It’s a historical fiction whose main character is a “holy idiot” type (the eponymous Barnaby). He’s fascinating, as is his talking crow, Grip (who inspired Edgar Allen Poe’s raven). It was very daring to place a “holy idiot” and a talking bird at the center of a novel, and I don’t think it works for a lot of readers, but I love it, and I love the crazed mob descriptions in the Gordon Riots scenes. They were an excellent warm-up for the French Revolution mob scenes he wrote in Tale of Two Cities, and they include some of the most bloodcurdling images of mob-mania I’ve read anywhere.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.