Social Conditions Affect Patients’ Health. Can Virtual Reality Train Future Doctors and Social Workers to Draw out That Information?

Interested faculty received a (pre-pandemic-and-social-distancing) demonstration of a virtual reality headset used by the Schools of Medicine and Social Work in a pilot program. Photo by Chris McIntosh

Real Doctors. Real Social Workers. Virtual Patients.

MED, SSW interdisciplinary pilot study of effect of social conditions on health

- Virtual reality patient interviews were piloted this spring for MED, SSW students

- Project, supported by Digital Learning & Innovation, is being evaluated

- Goal: teach teamwork before students are exposed to real-life work

Before choosing to be a doctor, Pablo Buitron de la Vega considered a career as a video game developer. As it turned out, life allowed him to blend both of his passions.

With two colleagues, this semester de la Vega (SPH’16), a School of Medicine assistant professor of internal medicine, piloted a potential technology-based innovation to the BU curriculum. They taught aspiring doctors, physician assistants, and social workers to broach personal social matters that affect health—level of education, job status, income, housing situation—with their patients.

Virtual patients.

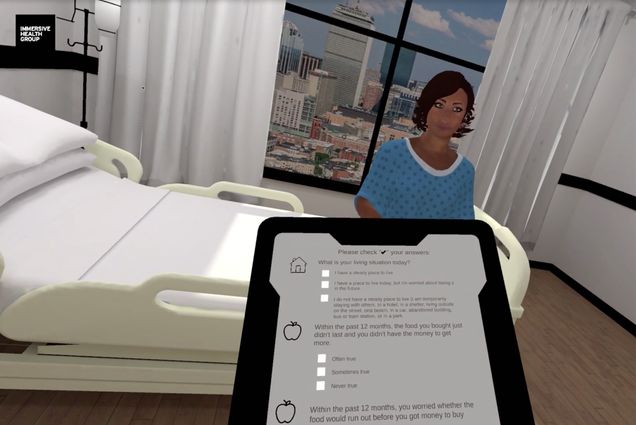

Offered a demonstration, this reporter, role-playing a School of Medicine student, dons a headset and finds himself in a Boston hospital room with an avatar patient named Aliza, an African American woman in a blue nightgown propped up on her bed. The vibrantly colored cityscape with the Prudential Center is visible behind her through the floor-to-ceiling window. Sunlight cuts a path across the floor. Your virtual hands, resembling a mannequin’s, clasp your fingers when you hit a trigger on handheld controllers, allowing you to pick up a virtual touch tablet containing questions:

What is your living situation today? Within the past 12 months, the food you bought just didn’t last and you didn’t have the money to get more—often true, sometimes true, never true? Do you need food for tonight? Do you have trouble paying for medicines? Are you currently unemployed and looking for a job? Are you interested in more education?

Touching the screen by each question with a virtual finger checks off the answers, just like a real tablet.

After Aliza—voiced from another room by de la Vega’s collaborator Aliza Stern, a MED instructor and Physician Assistant Program director of didactic education—answers the questions, clicking a green button on the screen with your virtual finger changes the scene. You’re transported to another room to meet virtual Linda, a School of Social Work student (role-played by third team member Linda Sprague Martinez, a School of Social Work associate professor and chair of SSW’s macro department). “Normally,” virtual Linda says, “you would just tell me about your patient, and then I would help you to think about the best way to connect them with resources,” based on Aliza’s needs in the questionnaire.

De la Vega, Stern, Sprague Martinez, and 15 students from MED and SSW spent the semester piloting this technology and its approach to learning. The project had expertise and grant support from Digital Learning & Innovation (DL&I), BU’s incubator for novel enhancements to education, which connected the team to a New York company that custom-built the software for the pilot project.

Students in the pilot were able to “meet” in the virtual hospital while sitting miles apart on the Charles River and Medical Campuses. Foregoing a commute to the latter to hook up with her MED peers was a welcome convenience for Joseli Alonzo (SSW’20), who says that—aside from a slight headache after using the headset and the initial disorientation of entering and exiting VR mode—she found the collaboration with MED peers invaluable.

The images above are from a virtual reality exercise that was piloted for students in the Schools of Medicine and Social Work. Images courtesy of Pablo Buitron de la Vega

“I plan on working in healthcare settings, so learning how to collaborate in multidisciplinary teams is a must for me,” Alonzo says. The multiple interactions in the virtual reality scenarios—MED student interviews patient, SSW student and MED student debrief each other—were more useful than just sitting “in an actual classroom, where we were all seeing the same location and possibly hearing and noticing the same information of the patient,” she says. “We were not only physically separated across campuses, but also within the actual consultation.”

Learning teamwork is just as important for budding doctors and physician assistants. “This was one of the most compelling features of this program,” says PA student Kendall Mulvaney (MED’21), “as it emphasized the importance of working as a team and acknowledging not only one another’s career title, but really understanding how the roles work together and can complement the other.

“Using the VR technology added a layer of realism that is often lost in ‘fake patient’ scenarios done in a classroom setting with fellow classmates,” she says. “It also simulated the real feelings of nerves and excitement of meeting and interacting with a new patient.” Yet by allowing her to be one step removed from reality by appearing as an avatar, Mulvaney adds, she took some risks in her interactions that she might have shied away from in a real-life encounter, giving her “more experience and confidence going forward.”

Virtual reality bridges classroom discussions and real-life observations, “so we can course-correct” when students stumble in the virtual scenarios, says Sprague Martinez. “When they get to the real patient, they’re much more comfortable.”

That’s the hypothesis, anyway. Analyzing results of the pilot to see if they bear out that hypothesis likely will take a semester or two, says Chrysanthos Dellarocas, associate provost for digital learning and innovation and a Questrom School of Business professor of management. “For now, the headsets are a little bit expensive, the technology is still to be refined. But I can clearly see a path to that.”

There are the occasional technical difficulties. During the demo for BU Today, Sprague Martinez—playing the SSW student—had a battery power shortage that made one of her avatar’s hands vanish. Still, says de la Vega, 90 percent of the students in the pilot reported that the virtual scenarios “felt like a real patient encounter.”

Dellarocas is unaware of a similar use of technology at any other university. He foresees exciting vistas of possibility. “Virtual reality has a bigger role to play in terms of facilitating student experiential training in scenarios and settings that are not very easy to offer” in real life, he says. “The whole point here is to see patients with various socioeconomic backgrounds, or various racial ethnicities. You want to train physicians how to behave in a way that is respectful, in a way that makes the patient feel comfortable, that’s inclusive.”

“The truth is, a lot of times, the medical students and PA students, they’re lacking in the skills and training social workers have,” says Stern. “The whole idea is to get them working together so they’re not so clueless when it comes time to be in clinic.”

For social work students, Sprague Martinez says, the benefits include learning to handle the subtle power dynamics of interdisciplinary care teams, which they typically aren’t trained in. Needing to work in tandem with doctors, she says, “social workers will sometimes be quiet in those settings,” so the virtual scenarios pair them with medical students. “They learn their role as a leader.”

Dellarocas says faculty with ideas for using technologies in education, from virtual reality to others, can pitch them to DL&I’s Digital Education Incubator, which provides seed funding and expertise in available technology.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.