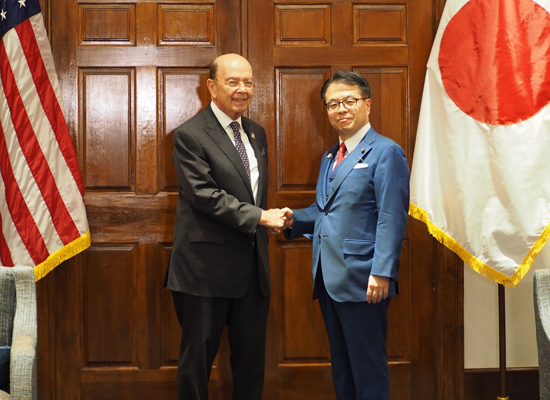

Hiroshige Seko (COM’92) and the PR of Politics

Japan’s METI minister talks about trade deals, Russia, and Fukushima

Hiroshige Seko (COM’92) (center) speaks to reporters in Tokyo in 2016 about the Japanese government’s plans for developing nuclear reactors. Photo by the Asahi Shimbun/Getty Images

It’s a daunting item to have at the top of your to-do list: Clean up Fukushima. Hiroshige Seko, Japan’s minister of economy, trade, and industry, is in charge of figuring out how to help his country deal with the aftereffects of the 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station after the March earthquake and tsunami. Completing the decommissioning of the plant could take 30 to 40 years and cost ¥21.5 trillion ($189 billion).

“How are we meant to bear the stunningly massive cost and pave the way for the decommissioning process, for which a technological solution has not yet been discovered?” says Seko (COM’92). “This is a very challenging task.”

At the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), Seko designs and communicates government policy with a remit that ranges from Fukushima to spurring Japan’s industrial competitiveness to ensuring economic cooperation with Russia. In summer 2017, he helped negotiate a trade deal between his country and the European Union, a major coup for Japan that resulted in the abolition of EU tariffs on Japanese cars (Seko oversees the automotive industry, among others).

Seko first entered politics in 1998, winning a seat in Japan’s House of Councillors, the upper house of the country’s legislative body. He was elected three more times and has held several senior positions in the Liberal Democratic Party. Before being appointed to his current role in August 2016, Seko was also a special advisor to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on public relations, parliamentary vice-minister of internal affairs and communications, and the longest-serving deputy chief cabinet secretary.

Before becoming a politician, Seko was a press and public relations professional at Japan’s largest telecommunications company, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (NTT). During his time with the company, he spent two years at the College of Communication as part of NTT’s selective study abroad program, at a rocky time for Japan and NTT. In 1989, just before he was chosen for overseas study, a bribery scandal forced Prime Minister Noboru Takeshita to resign and resulted in a criminal conviction for the former chairman of NTT in 1990. Determined to train its team in risk communication, “NTT suggested that I study at a graduate school of communications,” Seko says, and an acquaintance recommended BU. A course on corporate crisis management with Otto Lerbinger, a COM professor emeritus, was particularly useful, Seko says. (Lerbinger later cited Seko’s thesis, “Scandal Management,” in his book The Crisis Manager: Facing Disasters, Conflicts, and Failures.)

Politics, Seko says, has proven a natural outlet for his wider PR know-how.

“The mission of communications is not only unilaterally communicating information, but also listening to the other side’s opinions and changing one’s behavior accordingly,” says Seko, who was interviewed by BU Today at the end of Japan’s congressional session in June 2017. “That is also true in the world of politics.”

BU Today: What made you decide to pursue politics?

Seko: While the passing of my uncle Masataka Seko, who was a former minister, served as a trigger, there were two major reasons that I decided to abandon my career at NTT and run for a parliamentary seat.

First, I expected that I would be able to take advantage of my experience in the public relations field, because the world of politics has something in common with that field. Second, I thought that there would be some things that only I would be able to accomplish, because there were no politicians knowledgeable in the telecommunications field when I ran in the election.

How do you use your COM degree and your previous work in public relations in your current role?

In my own case, the experiences in the communications field at NTT and BU are at the roots of my career as a politician. Basically, corporate communications is about connecting companies with society. Political communications has something in common with corporate communications in that it both conveys the government’s policies to the voters and feeds back public opinions to the government so that their voices can be reflected in its policies.

Since taking office as a cabinet minister, I have noticed that many government employees take it for granted that the public will understand what is communicated by the government. In my work, I always approach communications with the goal of ensuring that the public understands our decisions.

Considering the economic impact of the Fukushima accident, what is your vision for the future of nuclear power in Japan?

The Japanese government is systematically examining the causes of the failure to prevent the Fukushima accident. The government intends to play the leading role in dealing with the aftereffects of the accident and to devote all necessary efforts to achieving the recovery of Fukushima and containing those aftereffects.

On the other hand, since the earthquake, the value of fossil fuel imports has increased steeply due to the effects of the suspension of the operation of nuclear power stations. Meanwhile, despite a steep drop in the crude oil price, the electricity rates for household and industrial use are higher than the pre-earthquake level because of the combined effects of suspending the operation of nuclear power stations, an increase in the feed-in tariff surcharge associated with growth in renewable energy generation, and the recent decline in electricity demand. These circumstances are placing a heavy financial burden on the Japanese people and industry. In addition, with the growing momentum of the fight against climate change as exemplified by the conclusion of the Paris Agreement, curbing CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use has emerged as a massive challenge.

If we take this into consideration, it will be essential to continue to use nuclear power, which is superior from the perspective of energy security, financial costs, and the fight against climate change.

Ensuring safety is the most fundamental consideration for the use of nuclear power, so we established an independent regulatory organization (the Nuclear Regulation Authority) based on the lessons learned from the Fukushima accident, and have developed new regulatory requirements that are the strictest in the world. We will strive to restore the people’s trust in nuclear power by constantly enhancing its safety.

What does the US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement mean for Japan?

What’s most important is that Japan and the United States are allies that share basic values. On the economic front as well, Japanese companies are generating many jobs and large amounts of investments in the United States through local production. I believe that it is important for Japan and the United States to develop a closer economic relationship and work together to promote prosperity around the world, including the Asia-Pacific region.

The US announcement of its withdrawal from the TPP was very regrettable, but the strategic significance of the TPP, which creates high-level rules in the Asia-Pacific region, remains unchanged. Currently, the 11 remaining countries are discussing options for realizing early effectuation of the TPP.

Going forward, I hope that Japan and the United States will continue to cooperate to establish high standards for trade and investment and discuss methods of spreading free- and fair-trade rules throughout the Asia-Pacific region. We also intend to develop closer cooperation between the Japanese and US governments in order to correct illicit trade practices employed by third-party countries.

What’s it like to be in charge of economic cooperation with Russia in the current political climate?

First of all, it is indisputable that as a G7 member, Japan should implement the sanctions imposed against Russia in relation to the Ukraine issue. On the other hand, it is true that Japan is facing an extraordinary situation in its relationship with Russia, in that the two countries have yet to conclude a peace treaty, despite more than seven decades having passed since the end of World War II. In consideration of this point, Prime Minister Abe has expressed his intention to make steady progress toward the conclusion of a peace treaty based on his relationship of trust with President Vladimir Putin.

Concerning economic cooperation with Russia, at the Japan-Russia summit meeting held in Sochi in May in 2016, Prime Minister Abe proposed an eight-point “cooperation plan” to President Putin. As the minister in charge of this cooperation, I have been putting the plan into practice since September. [Editor’s note: The plan includes a commitment to cooperate on issues ranging from healthcare for Russia’s aging population to developing industries and export bases in the Far East.]

For my part, I would like to create a virtuous cycle of the economy and politics in which the deepening of the economic relationship through the implementation of the eight-point cooperation plan will lead to the stabilization of the bilateral political relationship between our countries.

As someone with career experience in public relations, what do you think is the most important message Japan should communicate to the world?

I think we should share the spirit of wa (harmony) and the spirit of being conscious of reducing waste and saving energy, as Japan has traditionally done, evident in the consistent use of the term mottainai, which means “wasteful,” in public discourse in Japan. I believe that spreading these spiritual Japanese cultural tenets around the world is important when we consider methods of solving global challenges such as climate change and food shortages.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.