Overseeing Behind-the-Scenes Magic for a Galaxy Far, Far Away

Alum is visual effects producer for Star Wars franchise

Janet Lewin (CGS’90, COM’92), with droid BB-8 in a screening theater at Lucasfilm in San Francisco, takes the Star Wars groundbreaking visual effects from ambitious ideas to fully executed realities. Photo by Mitch Tobias

IN THIS STORY

Princess Leia, sporting the hair buns that launched a thousand costume wigs, smiles in full view of the camera. Her face is young, radiant.

The closing scene of 2016’s Star Wars spin-off Rogue One showed one of the canon’s most beloved characters—Carrie Fisher’s wisecracking, gun-toting royal—in her youthful prime. Yet Fisher, who found stardom playing the role of Leia in the 1970s, was in her late 50s when Rogue One was being made. When Fisher first saw a shot from the scene, she thought it was an outtake from her performance in the original Star Wars movie. In fact, it was a brand-new shot—generated by computer. Under the oversight of Janet Lewin (CGS’90, COM’92), visual effects artists spent two years creating computer graphics versions of Leia and Peter Cushing’s villainous Grand Moff Tarkin for the movie. “It’s the art (and deceit) of CGI taken to new and perfected lengths,” said the Hollywood Reporter.

Actor Guy Henry (top) wore a head camera that captured his movements to help create a CG version of the character Grand Moff Tarkin (bottom). Top: Jonathan Olley, © 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reserved; bottom: © 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reserved

Taking groundbreaking visual effects (VFX) from ambitious ideas to fully executed realities is part of Lewin’s job as vice president of visual effects for Lucasfilm. She’s the VFX producer on the production company’s Star Wars films, including the forthcoming eighth episode—The Last Jedi (December 2017)—a spin-off Han Solo movie (2018), and a ninth installment scheduled for 2019. She’s also executive VFX producer on the movies for Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), Lucasfilm’s VFX and animation studio. When filmmakers and effects supervisors first brainstorm how to stage epic space battles or make audiences fall for a cute droid, Lewin helps them determine what technology to use, and how. She hires the people who pull off the computer graphics (CG) magic, checks in on-set, and keeps schedule and budget on track.

Millions of kids—and grown-up kids—would probably do Lewin’s job for free. Star Wars is one of the most beloved and highest grossing series in history, hauling in worldwide box office receipts of more than $7.5 billion. The films are the heart of a multibillion-dollar, Disney-owned franchise that also encompasses several TV series, a slew of books, video games and comics, a king’s ransom in merchandise, and theme park attractions like Star Wars Land, opening in Disneyland and Disney World in 2019. Lewin is also the ILM executive producer of visual effects for Star Tours, the motion-simulator ride at Disney theme parks, and for the Millennium Falcon ride in Star Wars Land.

Revenge of the Sith “was a giant machine. We were doing 2,000 shots on that movie, which was very large for a film at that time” compared to the standard 350 shots. —Janet Lewin

As the Star Wars empire has expanded, so has the role of VFX: it’s now bigger than the films’ other departments combined. Over more than two decades with ILM, Lewin has seen the company grow from a facility of some 200 people working mainly in model shops and on stage sets to a computer graphics–driven network of four studios with 2,000 people in San Francisco, London, Vancouver and Singapore.

“Now you really can’t make a movie without visual effects, especially not blockbuster movies,” says Lewin, who has worked on such films as Hulk, and the Star Trek, Indiana Jones, and Pirates of the Caribbean franchises. “Visual effects are a huge component of storytelling.”

But for every awesomely creepy alien or undead pirate brought to life on-screen by a computer, there’s a ludicrously overblown superhero battle, and directors are starting to get misty-eyed for the kind of homemade effects work that characterized much of the Star Wars early years. Lewin’s task is to find the right balance between honoring the essence of the original trilogy while pioneering new technologies.

Training of a VFX Jedi

In early June 2017, there are seven weeks of postproduction left to go on The Last Jedi—and hundreds of VFX shots to complete. But Lewin looks relaxed as she strolls through the halls of the Lucasfilm campus in San Francisco’s Presidio park. The buildings are stuffed to the gills with Star Wars models, paintings, autographed posters, and life-size replicas of characters like Darth Vader and R2-D2 (staff occasionally take him for a spin around the halls).

Lewin works on the same floor as Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy and George Lucas, in an office papered with schedules bearing secret code names for the Star Wars films. But her first job at the company was as a temp in ILM’s purchasing department in 1994—a job she got with help from a family friend at the studio. She worked her way up over the next two decades, serving as a production assistant on 1996’s Mission: Impossible and executive assistant to Chrissie England, an ILM effects producer who later became the company’s president.

Her first Star Wars film was Revenge of the Sith (2005); she was a visual effects producer on it. “It was a giant machine,” she says. “We were doing 2,000 shots on that movie, which was very large for a film at that time” compared to the standard 350 shots. She and her two-year-old son got to appear as extras in a couple of scenes. In one, she played an opera guest, in another, she and her son were part of a funeral procession.

Janet Lewin (right) with VFX supervisors and producers on Revenge of the Sith, dressed as extras for the film. David Owen, © 2004 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reserved

During the roughly two years a Star Wars film is in the making, Lewin juggles enough tasks to make C-3P0’s head spin. Early on, she helps evaluate what a film’s thousands of effects shots might cost—“I can look at a script and say within a range of $10 million where I think the visual effects budget will net out.” She hires the VFX leadership and their on-set and postproduction teams, who report to her. During filming, she visits the set, making sure directors pass along key shots to the VFX team to guide the development of computer graphics assets, like spaceships or the look of a particular planet. She troubleshoots any budget overages and triages new ideas to keep a film on track for its release date.

“There hasn’t been a director we’ve talked to who hasn’t explored the idea of wanting to go back to miniatures and motion control and even more creature shop effects than visual effects for some of the character work.”—Janet Lewin

Over the course of her career, Lewin has worked with many top directors, including Steven Spielberg (Hon.’09), Michael Bay, and Woody Allen. It took some time to get used to the different personalities and learn the best way to approach a problem. One thing she says she learned the hard way: don’t just drop the bad news that a film is going over budget; offer ideas for offsetting the overage, like cutting back on shots in a different sequence or using an actor instead of CG. “It’s a constant conversation about what [directors] want to achieve creatively and what their options are for doing that—how to balance it within the budget and with the time and resources we have.”

Digital force: light side, dark side

In 1977, when writer-director George Lucas enthralled audiences with the first Star Wars movie, technological limitations forced him to rely heavily on handcrafted, practical effects. But he also pioneered new technology: elaborate space battles came to life through realistic stop-motion animation and detailed miniatures filmed with motion-controlled cameras. When Lucas resurrected the franchise at the turn of the century with three prequel movies, he was eager to innovate again.

Lucas “embraced new things—HD, digital format versus film—and then he really wanted to push ILM to lead the way in digital environments and digital characters—Jar Jar Binks being the first foray into digital characters,” says Lewin. But despite grossing more than $2 billion worldwide in theaters, the prequels received some stinging reviews and alienated many fans of the first trilogy. “Perhaps the freedom of limitless shot designs and options, camera moves, and animation created shots that were difficult to connect with emotionally” for actors and audiences, Lewin said in a Disney Cruise presentation.

Practical effects—achieved physically instead of on the computer—have been coming back in vogue over the past few years. Technology news website The Verge dubbed 2015 “the year of Hollywood’s practical effects comeback,” citing audience nostalgia and weariness of computer-generated effects among the reasons for the revival.

“There’s been a rejection of giant visual effects movies that nobody can relate to,” says Lewin. With the same studios working on blockbuster after blockbuster, she says, it’s easy to see why audiences might think, “I’ve seen that shot before, but now they’re making it 10 times bigger with a thousand more explosions just to show that they can.”

Star Wars’ newest crop of filmmakers are wary of that pitfall. “I think that there hasn’t been a director we’ve talked to who hasn’t explored the idea of wanting to go back to miniatures and motion control and even more creature shop effects than visual effects for some of the character work,” says Lewin. These directors, she says, want to tap into the emotions they felt when they first watched those original Star Wars movies, while also respecting the sophistication of modern audiences.

“If you think of Episode IV and the first time you see the Star Destroyer go over the camera, you remember that shot as being just absolutely awe-inspiring, and that it was massive and emotional and you couldn’t believe your eyes,” says Lewin of the 1977 film’s opening sequence. “But when you actually look at the shot, it still is amazing, and the shot design itself is still remarkable, but it wouldn’t hold up for today’s audiences. So we tried to figure out, ‘OK, what are the pieces [of technology] that would make a difference?’”

© 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reserved

© 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reservedStudying the original trilogy was step one for the filmmakers and VFX leadership. “We thought about what limitations there were: the models that were built, and how the elements were photographed,” says Lewin. “Even if they’re not as sophisticated as some of the assets and camera moves in today’s films, they felt grounded and real, and so we tried to figure out why, and how to replicate that.” They also talked to VFX artists who worked on the movies—some of them are CG artists on the reboot.

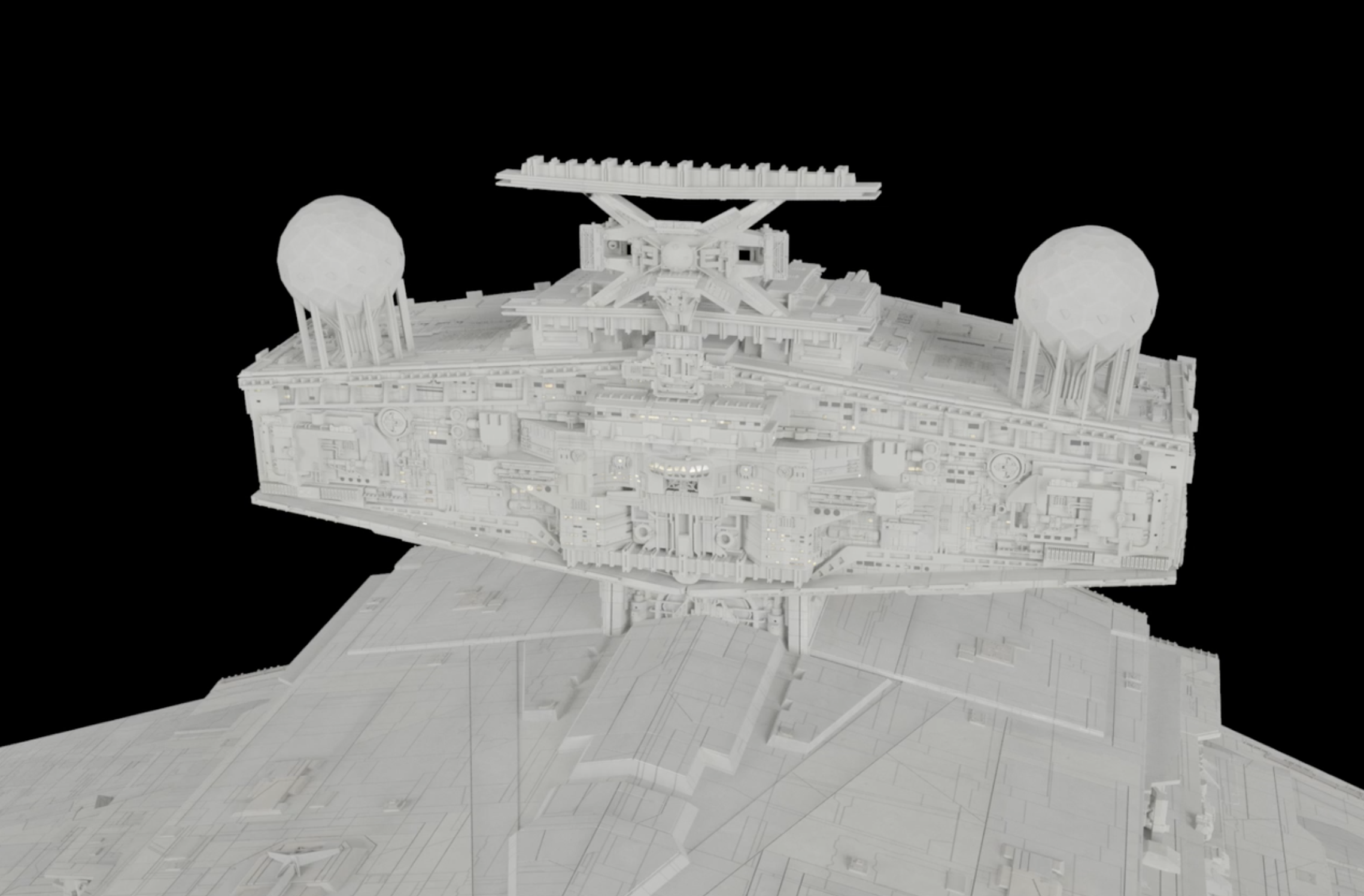

Imperfection, it turned out, had charm. The team located the original rocket and car model kits from the 1970s whose parts (“greeblies”) were used to make the miniatures for the first trilogy. “The Death Star has all these little tiny greeblies all over it, and so does the Star Destroyer, and they’re imperfect and don’t necessarily serve a logical purpose, but they add detail and scale and have a handmade quality to them,” she says. When creating some of the starships for Rogue One, the team scanned those original kit parts (left, top) to use them on CG assets to mimic the look of miniatures (left, below).

“It’s kind of a funny, full-circle thing,” she says, “because one of the reasons why miniatures were abandoned in favor of CG was because people thought miniatures looked fake, and then we get the criticism that the CG assets look fake and we need to go back to miniatures.

Watch a space battle from Rogue One come together behind the scenes. Video by Industrial Light & Magic, courtesy of Lucasfilm

“I think what we learned is that a hybrid is going to be the best way: to not rely too heavily on CG for everything, or practical for everything, but really have it be a blend.”

In The Force Awakens, BB-8’s role was split between a physical droid operated by a creature effects artist (below: top right and bottom left) and a computer-generated stunt double (bottom right). The VFX team also scaled back on showy CG camera moves. “You subconsciously are aware of the fact that a camera could never make that move, and so you lose engagement with the point of view of the shot,” says Lewin.

Clockwise from top left: Photos by Christian Alzmann, David James, Lucasfilm, David James. All © 2015 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights reserved

While Lewin is mum on what visual effects are in store for The Last Jedi, she says that “Rian [Johnson] is a very grounded director…and there’s a lot of location work, and a lot of stuff that was achieved practically. It’s a really great blend of visual effects and live action.”

As Lewin looks to the future of VFX in the franchise, digital humans like Rogue One’s Leia and Tarkin continue to be “the holy grail of visual effects,” she says. “There’s tons of other methodology things that we’re still exploring about how to make it more accurate and noninvasive and all of that, but we’re not quite there yet.” She’s also excited about trying to advance the integration of live action and visual effects—like building a planet’s cityscape with aerial photography plates and CG, then projecting it on-set behind actors using LEDs.

The world George Lucas created is unlimited, says Lewin. “You can go to any planet, you can explore new universes, and still make it feel like Star Wars. So, visually, there’s an unending world to explore.”

Star Wars, guerrilla-style

“Gareth Edwards wanted to shoot Rogue One as a documentary-style guerrilla-camera-move, handheld movie, which was really challenging and unique, and I think, just made it an exceptional visual experience,” says Lewin. “But one of our challenges was, how do we imbue our CG work with that same style? And Gareth has a very particular, unique, exceptional eye for composition.” The team created a virtual camera for Edwards to direct animation shots. “For example, we animated one of the shots that we did of the Star Destroyer coming together with the shield gate, and then we gave him a camera and he physically composed the shot. We then took his actual camera moves back into the shot….It gave the shots a more realistic camera-operator-driven feel that, I think, distinguishes it from other films and makes it feel more grounded as well.”

Take an inside look at the many layers of Rogue One‘s visual effects. Video by Industrial Light & Magic, courtesy of Lucasfilm

Women of the Force

Powerful women play major roles in the world of Star Wars both on-screen (think Leia, Rey, and Jyn) and off. “I think Lucasfilm is unique and kind of pioneering” in putting women in leadership roles, says Lewin. She ticks off names, among them current president Kathleen Kennedy and her predecessor, Micheline Chau, head of story Kiri Hart, and former ILM presidents Chrissie England and Lynwen Brennan, who is now general manager and executive vice president of Lucasfilm. Building up women’s numbers in technical roles on the visual effects side of the business—traditionally driven by men—is still a work in progress, she says, but Lucasfilm is working to increase diversity on all fronts. “Kathy has initiated a proactive diversity program with the British Film Institute. It’s basically providing standards of practice about how to reach out to diverse communities—women, people of color, and gender and sexual orientations, etcetera—to really diversify the workforce.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.