Combating Global Warming with Underwater Pictures

COM alum captures view few ever see for National Geographic

In 1954, underneath a dock at a summer camp in the Adirondacks, an asthmatic eight-year-old named David Doubilet put on a diving mask for the first time, stuck his head underwater and discovered an alternate universe. “Everything I knew in life…disappeared,” says Doubilet. “I was in a place where I was weightless, I could breathe, it was silent to a certain extent, and it was full of all sorts of interesting, mysterious shafts of light coming through the dock.” And then there were the fish.

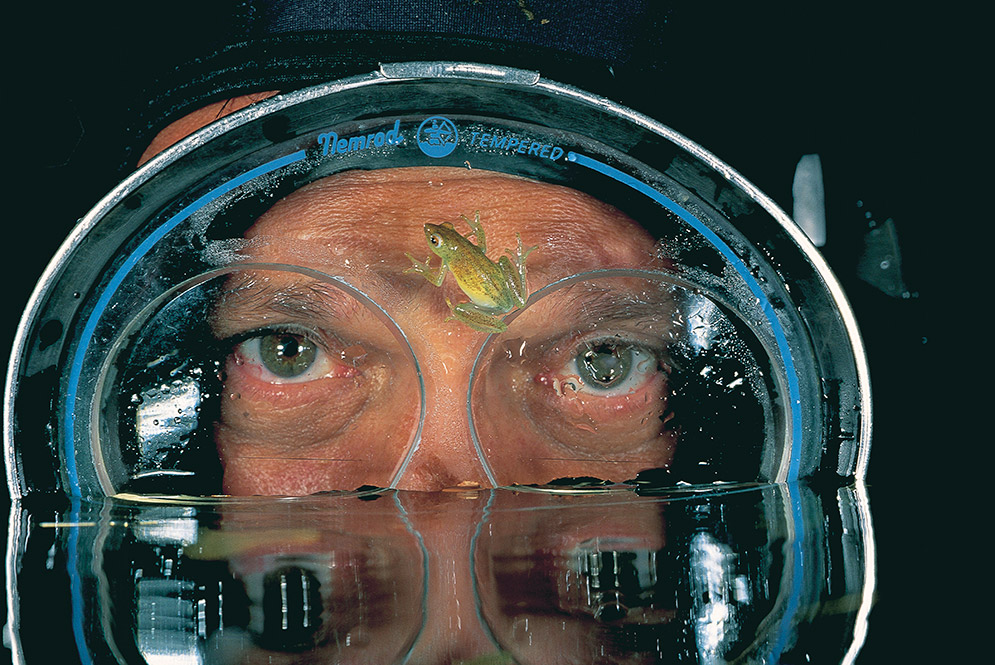

Since then, Doubilet (COM’70) has spent as much time underwater as he can, whether among icebergs in Antarctica, coral reefs in the Philippines, or crocodiles in Botswana. As an award-winning contract photographer with National Geographic for more than 40 years, he captures images of places and creatures many of us will never see firsthand. “Underwater photographers are on the front lines of telling people what this planet’s about,” says Doubilet, who frequently collaborates on assignments with aquatic biologist Jennifer Hayes, his wife and longtime photographic partner. His goal is to “open people’s minds to the sea”—and in doing so, draw attention to endangered species and the ongoing threat of climate change. “The biggest single story on Earth is Earth itself, and whether we can survive,” he says.

Doubilet’s scuba gear and camera give him—and by extension, National Geographic audiences—a privileged look at that story: images of endangered species, controversial practices such as dolphin hunting in Japan, the effects of global warming seen in melting glaciers, and the beauty and biodiversity of coral reefs that could be lost forever if temperatures keep rising. He hopes his images will “convince the unconvinced” that climate change is real and persuade them to take action.

“This is what I passionately care about, but on the other hand, you can’t go and say, ‘I’m going to save the planet with my pictures.’ The first duty of a photographer is to make a picture that captures people’s curiosity and imagination—in less than two seconds as you turn the page of National Geographic or look at a photo on your iPad, computer, or cell phone. It’s a difficult task, but if you can do it, then all of a sudden you can open their eyes to this complex, intensely beautiful underwater world.”

In November 2016, Doubilet and Hayes published a story in National Geographic that questioned whether opening Cuba to US tourists will threaten the Gardens of the Queen, a marine reserve that shelters endangered elkhorn coral. Their photos displayed the vibrant life in the reefs and mangroves: gleaming corals, a tiny endangered sea turtle hatchling, a crab huddled against the glowing red walls of a sea sponge. They hope the piece will help the site garner World Heritage status. They also often talk about climate change and its impact on aquatic environments through National Geographic Live tours that reach tens of thousands of adults and children worldwide.

Hayes says there’s evidence their advocacy works: images Doubilet shot of stingrays in the Grand Cayman Islands in the 1980s and of great white sharks in Australia and South Africa in 1999 helped pique interest in the fish and encourage floods of visitors to swim with rays or cage-dive with sharks. Such encounters, she says, inspire tourists to donate to conservation organizations—and the economic boom helps governments see the creatures as valuable resources to protect.

But getting the photos that tell these critical stories is no easy task. Water is a challenging medium, says Doubilet: “The [camera] housing’s difficult, the optics are difficult, the light is difficult, the time is short—a couple of hours a day at most.” The best-laid plans can fall through—he recalls unintentionally scaring off hippos with a camera-equipped motorized pontoon boat and watching an elephant step on a remote camera.

Sheer chutzpah

But sometimes, ingenuity, or sheer chutzpah, pays off. In 1999, he used a pole camera from a boat to get close-ups of sharks’ jaws. “You’d sweep the camera into the shark’s mouth and out before the shark bit down. If the shark bit down, he’d pull you into the water or his teeth would puncture the dome of the camera and it would flood. We flooded a couple of cameras.” In 2004, he swam among crocodiles in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Even with a guide toting an AK-47, night-diving in crocodile caves is foolhardy, he says, but yielded images of “unbelievably beautiful” forests of water lilies—and their inhabitants. Doubilet says he fears missing a good shot more than encountering deadly wildlife.

Doubilet is concerned about the future of environmental protections, given President Donald J. Trump’s avowed skepticism of man-made climate change. However, the public’s response to his work gives him encouragement. In December 2015, his photos were among the images projected on the exterior of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City as part of Fiat Lux, a light show raising awareness about climate change and endangered species. Seeing thousands of people cheer at the images “gave me an enormous amount of hope for what we can do about our planet and how much people desperately care about it,” he says.

Looking back, Doubilet is quick to list some favorite images—a diver encircled by barracuda in vivid blue water, seals “on a world of shrinking ice”—and locations, such as Antarctica and eastern Greenland. In December 2016, he and Hayes received permission to dive to the USS Arizona to cover the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor for National Geographic. “But if I’m really honest with you,” he says, “my favorite picture is the one I am about to take, and my favorite place is wherever Jennifer and I are about to go, falling off a boat into another world.”

Julie Butters can be reached at jbutters@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.