BU Postdocs: Who Are They and What Do They Want?

A portrait provides a starting point for a promising future

Sarah Hokanson gave her first “State of the Postdoc” talk Monday at the Medical School’s kickoff celebration of National Postdoc Appreciation Week. Postdocs are central to the University’s research mission, she said. She will give the same talk Thursday at 590 Commonwealth Avenue, on the Charles River Campus. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Sarah Hokanson, program director for Boston University’s Professional Development & Postdoctoral Affairs (PDPA) office, kicked off National Postdoc Appreciation Week at BU Monday by presenting a comprehensive, data-driven portrait of the nature and needs of the University’s roughly 500 postdocs.

Hokanson (CAS’05) says the data—gathered from offices across both campuses as well as through an anonymous postdoc survey—will help the University better serve its postdocs in a number of areas, such as minimum salary and professional development, that have been identified as key by the National Academy of Sciences.

Gloria Waters, vice president and associate provost for research, notes that most major research universities have policies concerning minimum salary and the length of time of postdoc appointments. In addition, she says, many other universities have put in place health benefits, not only for those postdocs who are classified as staff, but also for those postdocs who are not allowed by federal law to be classified as staff because they are funded through federal grants for “trainees” (about 20 percent of BU postdocs fall into this category). “The data Sarah has pulled together will provide important background about our own population of postdocs, as well as national data, as the University Council Committee on Research and Scholarly Activities works to put in place policies this year,” Waters says.

In addition, she says, Provost Jean Morrison has agreed to develop a mechanism this year that will enable the 20 percent of postdocs who are currently not allowed to be insured as University staff to enroll in health care benefits through the University as trainees. Developing these policies, as well as putting in place health care benefits for postdoc trainees, “will put BU in line with best practices nationally,” says Waters.

Hokanson delivered the first of two scheduled “State of the Postdoc” talks Monday at the School of Medicine, and she underscored the importance of the University’s 500 postdocs, or “productive scholars,” as she calls them, to its research mission. In the last two years, she says, BU’s postdocs have produced 736 publications and generated more than $800,000 in grant funding. “They’re contributors, and that’s a huge part of their identity,” Hokanson said in an interview last week. “We could not do the research that we do without them.”

“Now that we have all this data, we can begin to make changes in an evidence-based way,” she added. “The survey allows us to understand more about what postdocs are thinking and what their aspirations are. You can’t fully understand a group of people by statistics or by narrative alone, and this is the first time we’ve married the two. Now we can plan professional development in a way to help postdocs meet their goals.”

Hokanson compared BU to its peers, using data from the 2014 National Postdoctoral Association’s Institutional Policy Report and from the 2013 National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering. In terms of minimum salary, length of service, and postdoc demographics, BU’s numbers are at the national average, or better, Hokanson says.

Some key data, which PDPA collected with help from Institutional Research, Sponsored Programs, Research Operations, Systems & Analytics, the BU Libraries, and Human Resources:

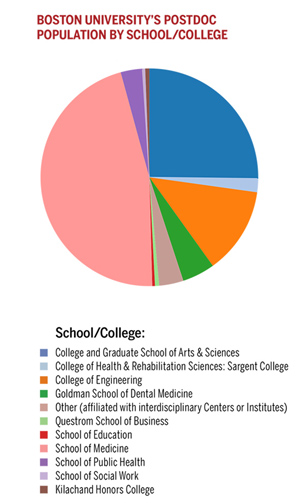

- As of August 5, there were 496 postdocs across the University. Of those, 56 percent have appointments on the Medical Campus, with the vast majority in the School of Medicine; 25 percent are in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences and roughly 13 percent are at the College of Engineering.

- International scholars, with temporary visa sponsorship, make up 53 percent, which is identical to the national percentage reported in the 2013 NSF GSS.

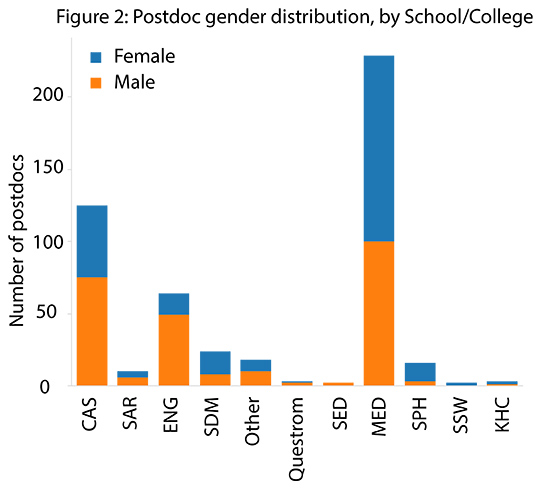

- The University-wide postdoc gender distribution is “almost perfect,” Hokanson says, at 51 percent male, 49 percent female. However, she notes, the 60 percent female majority in the large School of Medicine compensates for the lower 27 percent and 40 percent female populations within ENG and CAS, respectively. BU’s overall ratio is higher than 62 percent of other institutions surveyed by the National Postdoctoral Association, Hokanson says.

- Just under 2 percent of postdocs self-identify as African American or Black; 3.8 percent self-identify as Hispanic or Latino. These numbers require attention, says Hokanson, as the University considers ways for increasing its overall diversity. Of the institutions surveyed by the 2014 NPA IPR, 38 percent reported that they had less than 5 percent underrepresented minorities among their postdocs. Underrepresented minorities make up 9.5 percent of the national postdoc population reported in the 2013 NSF GSS.

- The average full-time salary for employee postdocs at BU is $49,232.27; the 2015 National Institutes of Health minimum salary is $42,840. Currently, 18.8 percent of BU’s postdocs fall below the NIH minimum, a matter that Hokanson says will be taken up by a policy committee next year.

- While the average length of appointment for most BU postdocs is around three years, 23 percent have been here longer than five years.

Hokanson notes that in its 2014 report, The Postdoctoral Experience Revisited, the National Academies of Sciences recommended that institutions set term limits for postdocs to not exceed five years of training, after which the expectation would be that postdocs move to a position outside their university or get promoted within the university to faculty or permanent researcher status. BU does not currently have a policy that enforces a five-year maximum limit, Hokanson says. Any talk of establishing term limits would require soliciting much study and feedback from across the campus, she says.

BU is one of a growing number of institutions across the country that are stepping up their efforts on behalf of postdocs at a time when restricted funding for research means that most postdocs in the life sciences will not find jobs in academia, but in industry, government, science policy, law, education, and other fields. PDPA, alongside BU’s BEST (Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training) Program, continues to offer workshops and other opportunities to help prepare its postdocs for the wide range of jobs that are available to them.

“I think we’ll see the postdoc position begin to transition,” says Hokanson, who became PDPA program director in February. “Funding agencies are thinking about postdocs, universities are thinking about postdocs, everyone is thinking about postdocs.” In the year 2000, fewer than 25 universities across the country had postdoc offices, she says. In 2014, there were 176.

Hokanson’s office conducted the postdoc survey in March 2015 in collaboration with BEST, and the survey evaluation was done by BU’s Clinical & Translational Science Institute. Of 525 postdocs surveyed, 177, or 34 percent, responded (74 from the Medical Campus, 93 from the Charles River Campus, and 10 that did not identify with a campus). One telling question: “At the start of your postdoc appointment at BU, what career goals were you considering?” The largest number of respondents chose as their first choice, “PI in a research-intensive institution,” and as second choice, “combined research and teaching position.”

“It reinforces the pipeline problem,” Hokanson says, referring to the well-documented lack of permanent academic jobs for all the postdocs who have spent years preparing for such positions. “But they’re already postdocs. Of course we can give them the data and tell them, ‘It’s great you want to be a PI, but faculty jobs are limited.’ But another important thing we can do is ask them, ‘How can PDPA and BU make you the most competitive candidate you can be?’ It isn’t our job to decide what career they choose; it’s our job to support them.”

Hokanson notes that one of the National Academies’ core recommendations in its 2014 report is adding professional development opportunities for graduate students that would help them identify when postdoc positions are an appropriate career step and when they’re not, so that postdoc positions stop becoming the default path after graduate degree completion. “We’re really lucky that we have our BEST program to address that recommendation directly to better prepare our biomedical graduate students,” Hokanson says.

In addition to gathering data through the anonymous survey, Hokanson has spent considerable time meeting with postdocs. At one meeting, the question of BU business cards—with the University logo—came up. BU business cards are an important networking tool, the postdocs told Hokanson, but they had no idea how to get them through the University.

This summer, Hokanson’s office began providing free business cards to all postdocs who request them. So far, close to 70 postdocs have placed orders. “It’s probably been the biggest hit,” Hokanson says. “That logo connects them back to this institution. It validates them. If they went to Vistaprint and made their own business cards, it wouldn’t look the same.”

PDPA has also begun providing $500 travel awards to help a limited number of postdocs go to conferences to present their research. Faculty volunteers assist Hokanson’s office in reviewing applications for the awards. Of 12 applications received over the summer, 2 postdocs received travel awards. Hokanson says she hopes to increase the number of awards next year. “Faculty seem to really appreciate the extra financial support,” she says.

Asked through the anonymous survey which skill they most wanted help with from the University, 71 percent of the postdocs who responded checked “grant writing.” Hokanson’s office will offer its first grant writing workshop in October.

Recognizing that postdocs have lab duties that make it difficult for them to attend workshops, PDPA will offer its first online session, Creating and Owning Your Individual Development Plan (IDP), in November. “The goal of that workshop is to empower postdocs,” Hokanson says. “It’s about them keeping an eye on their career. It also supports what the faculty does in writing their mentoring plans as part of their proposals.”

“PDPA still has a lot of work to do, but I am really proud of the progress that we have made in six months,” Hokanson says. “I look forward to working together with the postdocs to make sure that they have the best experience possible here at BU.”

Sarah Hokanson will give the second “State of the Postdoc” talk on Thursday, September 24, at 3 p.m. at the Science Center, 590 Commonwealth Ave., Room 109; free and open to the public.

Sara Rimer can be reached at srimer@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.