The ABCs of HPV

Why men, as well as women, need to be vaccinated

Here’s a rather sobering statistic: at least half of sexually active people will contract the human papillomavirus (HPV) at some point in their lives, and most won’t even know it.

Currently, 20 million Americans are infected with HPV, and another 6 million become infected each year, making it the most common sexually transmitted infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most people who become infected never show any signs or symptoms, and in 90 percent of cases, the virus goes away of its own accord within two years. But in other cases, HPV can lead to genital warts and cervical and other rare cancers.

In 2006, a vaccine was introduced in the United States to prevent some forms of HPV. The initial recommendation was that girls and young women ages 11 to 26 (and as young as age 9) should receive the vaccine. Additional research has found that giving the vaccine to boys and young men—especially before they become sexually active—can reduce their risk of developing genital warts and some associated cancers. In October, the Federal Advisory Committee voted to urge that young men ages 9 to 26 be vaccinated against HPV.

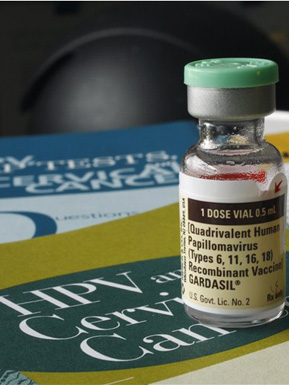

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil is the most common) protects against the types of HPV that cause most cervical cancer, as well as anal, vaginal, and vulvar cancers and most genital warts.

At present, there is no test on the market that can check overall “HPV status.” Women can be screened for the virus with a normal Pap test, but there is no test at all for men. Condoms may lower the risk of HPV transmission and HPV-related diseases, just one of the reasons why using condoms is so important. Even people with only one lifetime partner can contract HPV if the partner has previously had sex with an infected person.

Rebecca Perkins, a School of Medicine assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, has done research at Boston Medical Center on the attitudes of parents and providers about young women being vaccinated for HPV. She is currently collecting data on young men.

Perkins spoke with BU Today about why doctors now recommend the HPV vaccine for men as well as women and the dangers associated with the STI.

BU Today: Why should young people get the HPV vaccine?

Perkins: HPV is the most common sexually transmitted virus, and about 80 percent of people will have it at some point during their lives. It’s also classified as a human carcinogen. There are more than 40 types of HPV that are transmitted through sex or genital contact. It causes cancers of the cervix, penis, oropharynx (base of the throat), vagina, vulva, and anus. Cervical cancer can be prevented through screenings, but we don’t really have good screening measures for any of these other cancers.

Certain cancers, like oral and vulva, have been rising significantly over the past couple of decades. An October 2011 study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found that between 1984 and 1989, about 16 percent of oropharyngeal cancers were linked to HPV, but between 2000 and 2004, 72 percent were linked to HPV. This reflects different social behaviors, specifically more oral sex with different partners among the population, combined with a lower amount of cigarette smoking, which is what used to cause those cancers. So with less smoking and more oral sex, you saw a dramatic shift from only 16 percent being HPV-related to 72 percent being HPV-related. We see about 7,000 new cases in the United States every year.

In the past, doctors gave this vaccine only to women, and now they are recommending that men get it as well. Why is it important for men to be inoculated?

It’s important for men to get vaccinated for two reasons. The first is because it’s a contagious disease, so it’s to prevent transmittance from partner to partner. The other reason is for men themselves. Oral cancers are much more common in men than in women. Of the about 7,000 oral cancers that are diagnosed in this country every year, 5,000 will be in men. And there is no screening or preventive measure for it other than the HPV vaccination. I think this is the most important reason why men should be vaccinated.

Why wasn’t the vaccination recommended for men initially?

The first trials were done in women, looking at the end point of cervical dysplasia, also known as precancer of the cervix. They then decided to also do the trials in men and found that the vaccine reduced the risk of genital warts. It’s important, but since no one ever died from a genital wart, it was not enough of an indication to give it the strong recommendation that it has more recently gotten. That recommendation was given because researchers were actually able to show a decrease in anal precancers, similar to what was seen in terms of the reduction of cervical dysplasia in women.

Studies have shown that the vaccine works best in those who haven’t already been exposed to HPV. So if you’re sexually active, is it still worth getting the shot?

That’s a very good question and the answer is—definitely. Most people will acquire HPV within the first two years of their first sexual experience. There are about 40 different types of HPV that can infect the genital area, and the vaccine covers 4 of those types. Since the vaccine is a preventive vaccine, if someone has already been exposed to the HPV types that the vaccine wards against, the vaccine won’t work. A study found that 90 percent of college-age students will probably still get some benefit from the vaccine because they will have been exposed to none of the four types or only one or two of them. It’s worth the chance.

The HPV vaccine actually requires three separate shots. Is it important for people to receive all three?

Some vaccines will work with only one injection. There is some evidence that the HPV vaccine Cervarix—which is approved in this country, but only for females—may be effective with only one or two doses. But Gardasil, the most common vaccine, seems to require all three doses to actually work.

Are as many people getting vaccinated as expected?

As of 2010, the National Immunization Survey showed that 49 percent of females between the ages of 13 and 17 had received at least one dose of the vaccine and only 32 percent had actually completed the series. It’s certainly lower than the goal, which would be 80 percent, similar to any other recommended vaccine. When you compare it to when the chicken pox vaccine was introduced, and when the hepatitis B vaccine was started, it’s probably on par with those, because it always takes vaccines a while to catch on. Now that boys are in the mix as well, we’ll have to see how that plays out. Hopefully it will become more normal as part of the standard adolescent vaccine, but if the uptake in boys isn’t very good, and they’re included in the statistics, those numbers could fall even farther.

Are there any side effects or risks associated with the vaccine?

As with many vaccines, arm pain is the most common side effect. Also, some young women seem to faint when they get the vaccine, which could be just a reaction to the pain of the shot or maybe they’re scared of needles. It’s something that happens within 15 minutes of getting vaccinated, not something that happens three days later. Rarely, people can be allergic to things in a vaccine, but the rates of any serious side effect seem to be low or lower compared to other vaccines that we commonly give, like hepatitis and tetanus. We’ll have to see when we start giving it to more men if the males are fainting more than the females.

There has been some controversy surrounding the vaccine. What’s behind that?

Parents have two main concerns about this vaccine. Any time you have something new, people are afraid of the side effects. A lot of parents and doctors wanted to wait to see what, if any, side effects there would be. We have data on over 25 million doses in the United States and more data coming from Australia, Canada, and throughout Europe. The vaccine first came out in 2006, and I think at this point if there were any serious side effects we would have heard of them by now.

The other controversy was about giving a vaccine against an STD. Some parents are concerned that it might send the wrong message, that they were condoning sexual activity, that their kids wouldn’t use a condom. But we have found that it is actually a minority of parents that feel that way. It’s something that’s gotten lots of media coverage because it’s attention-grabbing, but it is really a minority of parents who will decline the vaccine for that reason.

How did you became involved in HPV research?

In 2007 and 2008, I did research at Boston Medical Center looking at parents’ attitudes towards HPV vaccinations. The patient population was generally low-income, minority, and immigrants. These parents were actually very accepting of the HPV vaccine—90 percent said not only were they in favor of the vaccine, but they went ahead and followed through getting their daughters vaccinated. I also did a medical record review, which didn’t show quite such rosy numbers, sort of on par with the national average, showing that about only half of girls finish up with the dosing of the vaccine. I’ve also done a little bit of work with providers, asking them their impressions around this particular vaccine. Providers themselves have different opinions: some think it’s the most amazing thing because it is a vaccine designed to prevent cancer, but some people are scared to bring up a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection with the parent of an 11-year-old girl. Our current research project involves interviewing parents of boys, and we are still collecting data.

At BU, students can receive HPV vaccinations at Student Health Services; the cost is $165 per dose, and insurance usually covers it. Planned Parenthood, at 1055 Commonwealth Ave., offers the vaccine free of charge for those who are 19 to 26, have no health insurance, and meet financial criteria.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.