From the Field – The Loud, Rowdy Rainforest and its Many Surprises by PhD student, Frank Short

From the Field: The Loud, Rowdy Rainforest and its Many Surprises

By Frank Short, PhD Student, Boston University

Despite common misconceptions, the rainforest is in some ways more like a city than a tranquil escape. The rainforest is crowded, loud, and busy. Only the rain provides respite from the commotion, with all animals reluctantly falling quiet in deference to its natural power. No matter how long you have spent in the field, the rainforest during a strong storm never ceases to amaze with its beauty. Rushing to rescue our barely dried clothes, we may curse its inconvenience, but the calm cool wonder it bestows always ultimately assuages any grievances.

Ironically, that very same tranquility has become the bane of my existence as a bioacoustics researcher. That cacophony, that sound of thousands of individual animals bellowing out to announce their existence, is exactly what I am interested in. Nothing could prepare me, though, for the auditory feast I experienced first walking into the Bornean rainforest of Gunung Palung National Park. The overwhelming diversity of animal vocalizations heard here can barely be put into words. By far, however, the roar of a flanged male Bornean orangutan is the king of the rainforest when it comes to impressiveness. I will forever remember the first time I had the privilege to experience it in person.

While I first came to the Cabang Panti field site 3 years ago in 2022, there were no males present the entire duration of my stay. This time, though, I arrived right at the tail end of the mast, when thousands of trees fruit in synchrony. This abundance of food resources means that everyone comes to the party, so I knew there was a much better chance of me catching some flanged males. As it turns out, I was right. The first flanged male I was able to follow was Balon, named for his notably massive throat sac.

I was immediately impressed by his size compared to other orangutans I had followed. Flanged males are often twice the size of adult females, and the way that they traverse the trees of the rainforest is far heftier and, to be honest, threatening. However, my objective of hearing a long call was more of a test of patience than what I had expected. Balon would begin the characteristic low grumblings I had heard so many times from long call recordings, but he never progressed to the trademark “roar” that marks a true long call. Every time he would begin to grumble, I stood there holding up my recorder on a makeshift stick in quiet anticipation. Ultimately, it was another male known as “Mr. Perfect” for his immaculate features that would bestow me with my first true long call experience. I will never forget how he vigorously threw several branches to the ground before letting out a fearsome classic long call with all of its typical parts: a build up of low grumbles, a crescendo of loud roars, and then a slow cooldown of deep booming “sighs”. I remember standing there with probably the stupidest wide-eyed smile I’ve ever displayed in my life.

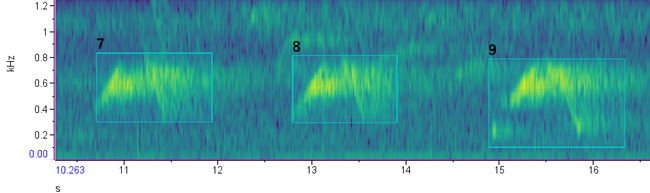

The research for my dissertation entails the placement of passive acoustic recorders throughout the study area to assess the presence of orangutans and other primates. These devices can record continuously for hundreds of hours, and with the power of artificial intelligence models can parse through thousands of hours of recordings across multiple sites to gather detections of these species from their vocalizations.

This has meant traversing through all of the eight habitat types found in these extremely diverse forests, whether it be through flooded peat swamps or up ridiculously steep mountains. Often times, this also causes me to have to bushwack through less-frequented trails, all while dealing with the superbly annoying and spiky rattan that hooks into your clothes and skin, or massive tree falls that greatly hinder or completely halt your path. However, this kind of exploration also comes with some perks. It was on one of these especially frustrating excursions that I came across one of the most elusive and shy primates in the Bornean rainforest: the tarsier.

Tarsiers are notoriously rare to encounter. Many people who have worked in Gunung Palung National Park for over 20 years have never seen one. This is because many tarsier species, such as the Horsfield’s tarsier that inhabits the park, are primarily nocturnal and solitary. To further complicate things, many of their vocalizations are inaudible to human ears and exist in the ultrasonic range above 20 kHz. So, you can imagine my surprise when after dodging rattan and tripping over tree roots in the peat swamp I found myself face to face with one of these creatures. Even more surprising was that it was in broad daylight, in the middle of the afternoon. I clearly must have awoken it from a deep sleep with my rude and sloppy stumbling. It blinked while looking at me with its massive eyes (the largest of any mammal relative to body size) as it clung to a tree probably only about 10 meters away from me. I was lucky to have my phone on me and the ability to take a picture.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from the wet swamps, in the lowland areas of the park, are the higher elevation habitats that lead up to the summit of the mountain at 1116 m elevation (3661 ft). There are two main trails that ascend to different parts of the mountain – UB and GP. Because I wanted to increase my sample size as much as possible for my research, I knew I would have to climb up both of them. The southern trail of UB has a bit of a reputation, and I soon found it was very warranted. At many parts, you’re not so much hiking up a mountain as you are rock scrambling. There is not actually any clearing at which point you can get an unobstructed and beautiful view of the rainforest below. Still, UB offered me my first experience of the magical montane habitat. Here, you are greeted by sparser vegetation and trees, unique mosses and fungi, and mysterious intermittent clouds of mist.

I knew I had a better mountain climbing experience awaiting me later on in GP. As the more cheerful and popular brother of UB, GP possess two particularly crowd-pleasing characteristics: a more gradual ascent and the promise of a great view. Yes, the ascent was more gradual, but it was still a journey with a more than 3000 ft climb in elevation. Soon, though, I had a first quick glimpse of the sky, and shortly after we came across a view that surpassed all expectations. From this vantage point, you can see from the great swaths of the rainforest that lie below, to twisting rivers, and even at some points to the sea. This was clearly the reward for the horrors of UB. GP even had more gifts to bestow still. Only a couple of dozen meters ahead of this gorgeous view was a crystal-clear flowing mountain stream. It’s still the best water I’ve ever tasted.

The next step in my journey is to visit six of the Hutan Desa (Village Forests) overseen by the Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program / Yayasan Palung. These village forests are part of the Indonesian social forestry initiative, which grants communities the legal land title to the forests they have traditionally used. Like my previous experiences, I know that this part of my adventure will be challenging in new and unforeseen ways. I just know that something amazing is waiting right around the corner.

Read the full story in the Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program newsletter.