IoC Survey Reveals Mayors’ Thoughts on Last Year’s Protests against Police Brutality

The latest Menino Survey of Mayors, conducted by BU’s Initiative on Cities in 2020, found that almost 40 percent of mayors surveyed do not believe that police violence is a problem in their community. Photo by Anik Rahman/NurPhoto via AP

IoC Survey Reveals Mayors’ Thoughts on Last Year’s Protests against Police Brutality

Most acknowledge unequal treatment by police, but oppose major funding reallocations

In the past year, police in US cities shot and killed 991 people. About half of those people were Black, even though Blacks account for less than 13 percent of the nation’s population. The Washington Post reports that Black Americans are killed by police at more than twice the rate of white Americans, and that Hispanic Americans are also killed by police at a disproportionate rate. Such racial disparities in law enforcement have been recognized by Black Americans for decades. In May, when the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis ignited protests against police killings and brutality in dozens of US cities, it was the fuel that fed the fires across America.

In the wake of the protests, BU’s Initiative on Cities (IoC) annual Menino Survey of Mayors surveyed US mayors about whether they believe police violence is a problem in their community, what they saw as their role during the protests in their communities, and their plans to reform their police departments. The 2020 Menino Survey of Mayors report, released Wednesday, January 27, invited responses from all mayors of cities with 75,000 or more residents; in total, 130 mayors across 38 states participated.

According to IoC director Graham Wilson, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of political science, the research revealed “a striking contrast between national concern over policing and mayors’ satisfaction with their own police forces.”

Key findings include:

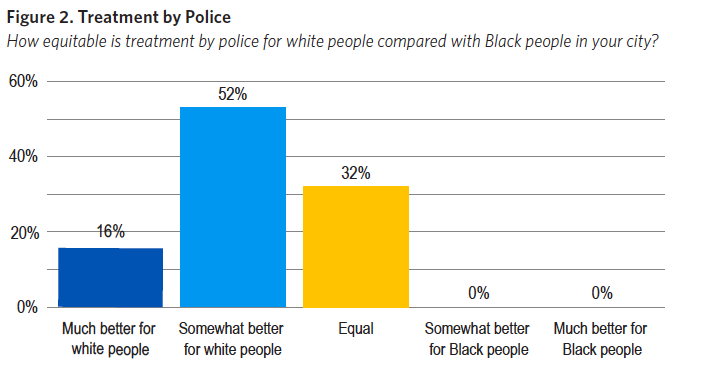

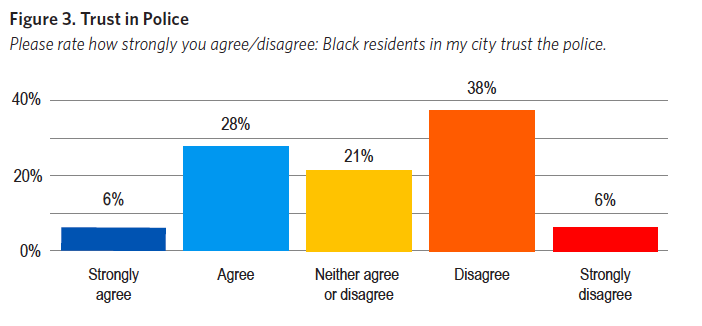

Mayors see stark racial disparities in local policing practices, but responses are mixed as to whether this inequality translates into mistrust of the police. An overwhelming majority of mayors believe that Black people are treated worse by the police compared with white people. However, they are considerably more mixed when asked whether Black people mistrust the police. A plurality of mayors believes their city’s Black residents mistrust the police, while a sizable minority disagrees.

A majority of mayors believe that protests against police violence during summer 2020 were forces for positive change in their cities. There were sizable partisan differences, with Republican mayors over 30 percentage points more likely than Democratic mayors to perceive protests negatively. A third of mayors said they participated in the protests, while another fifth described their roles as communicating with, and listening to, protesters and the police.

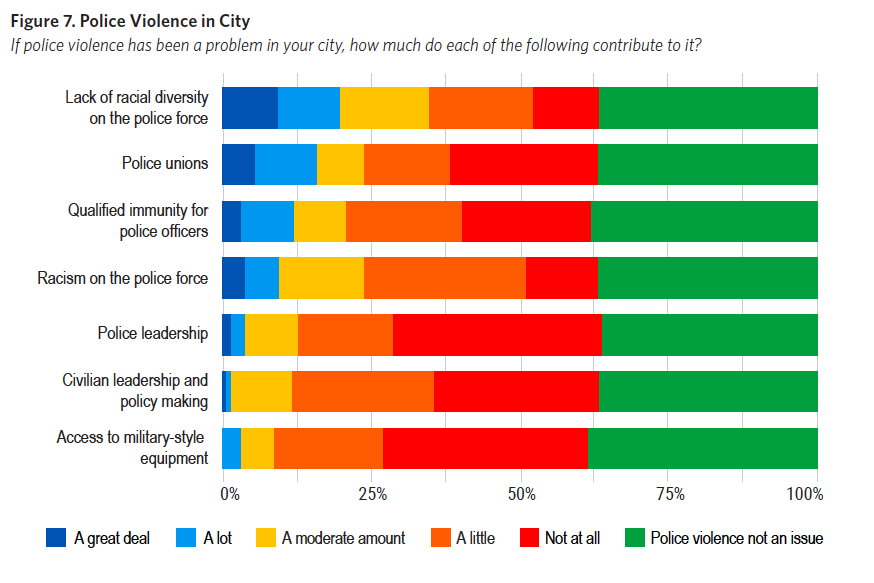

Almost 40 percent of mayors surveyed do not believe that police violence is a problem in their community. Republican mayors were 13 percentage points more likely to say that police violence was not an issue in their cities; still, 29 percent of Democratic mayors had a similar opinion. Among all mayors surveyed, just over half believe that both lack of racial diversity of officers and racism on the force contribute to police violence at least a little.

An overwhelming majority of mayors believe that their police departments do a good job of attracting individuals well-suited to being police officers. Despite mayoral recognition of racial inequality in the police ranks and of disparate treatment of constituents based on race, 80 percent of mayors believe their police departments do a good job of attracting candidates well-suited to the job.

Very few mayors support shrinking their police budgets. Only 12 percent of mayors described their police budgets as too large. An overwhelming majority believe their budgets are just right, with 8 percent describing their budgets as too small.

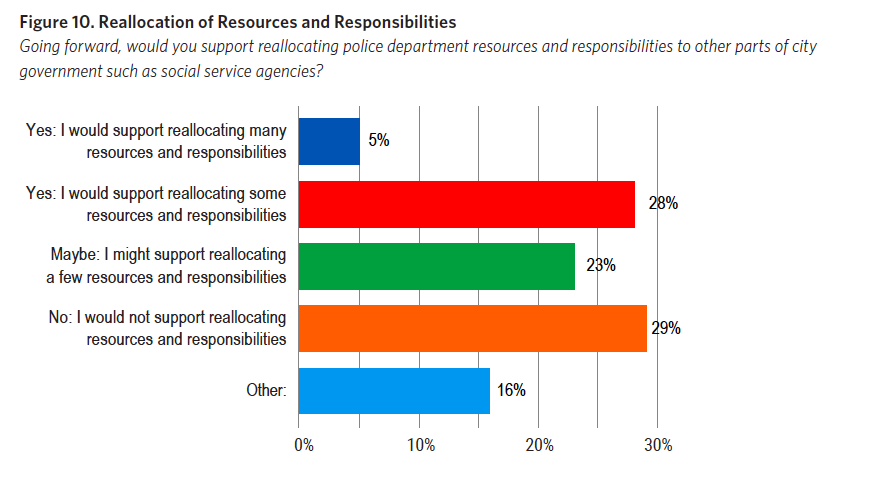

Mayors support a wide variety of small reforms to their police department, but few endorse broader department restructuring. Only a third of mayors surveyed endorse reallocating at least some resources and responsibilities from their police departments to other city services. Similarly, when asked an open-ended question about desired reforms, just 16 percent of mayors support bigger structural changes. They back a variety of other reforms, including increasing diversity on their police forces and civilian review boards.

A report on the survey, written by David Glick and Katherine Levine Einstein, both CAS associate professors of political science, and Maxwell Palmer, a CAS assistant professor of political science, suggests that solutions to the problem will not come easily. The authors note that mayors who hope to reform their police departments face the formidable challenges of powerful police unions and mixed public opinion about structural reform.

“Even in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s killing,” they write, “only 33 percent of Black people and 23 percent of white people favored broad structural reforms to the police and reinvent[ing] our approach to public safety.” Reforming things within the existing system, however, was endorsed by 64 percent of Black people and 56 percent of white people.

The survey also revealed several politically partisan divides in mayors’ perception of race-related issues. Asked How equitable is treatment by police for white people compared with Black people in your city? a strong majority (68 percent) said police treat white people better than Black people. When the political affiliation of mayors was introduced, the survey found that 73 percent of Republican mayors believed that police treat Black and white people equally, while only 14 percent of Democratic mayors believed that that was the case.

Einstein says previous Menino Surveys of Mayors have also shown deep partisan divides on perceptions of racial equity, with Democratic mayors far more likely to recognize racial disparities and inequities in their communities. “The two major parties have generally become increasingly divided on racial issues,” she says. “And this racial and partisan polarization, in turn, shapes attitudes towards policing.”

Elsewhere, the survey found more unanimous opinions. Asked if they thought that Black people in their cities trusted the police, mayors were consistent across party lines: 44 percent said Black residents distrust the police. The authors note, however, that such agreement suggests that mayors of both political persuasions may be out of touch. National opinion polls conducted last summer indicated that only 36 percent of Black people trust the police, compared with 77 percent of white people.

Asked about the mayors’ roles during protests, 32 percent said they were participants, and some said they were strong supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement. About 15 percent said they were supportive, but remained behind the scenes. About 16 percent said they supported both sides in protests, and 13 percent said they were supportive of police efforts.

The survey found that mayors largely acknowledge inequality in police treatment of Black people, and support protests against police violence in their cities, but it also found that 38 percent of mayors don’t believe that police violence is an issue in their community. Here the researchers found another partisan divide, as Republican mayors were 13 percentage points more likely to say that police violence was not an issue in their cities. Assuming a broader perspective, the authors point to a disconnect with data on the widespread nature of police violence: in only one of the nation’s largest 100 cities was no one killed by police between 2013 and 2019. “While there is certainly variation in the incidence of violence across police departments,” they write, “virtually all police departments struggle with officer-involved shootings and other nonfatal forms of police brutality.”

Questions about the reallocation of resources revealed little support for the politically sensitive issue. About 29 percent said they would not support reallocating police department resources and responsibilities to other parts of city government, such as social service agencies. A nearly equal number—28 percent—said they would consider reallocating some resources.

“Cities are generally really fiscally constrained,” says Einstein. “That makes it hard to reallocate money—especially in a moment where, as we showed in our COVID-19 report—mayors are going to have to make really tough budget cuts in the coming months. This challenge is compounded by the tricky politics of policing; police unions and departments are politically powerful, and mayors worry that police budget cuts could translate into crime spikes that are deeply unpopular with constituents. In short, constraints from powerful interest groups and public opinion, especially from white constituents, make mayors reluctant to cut their police department budgets—even if they recognize racism and brutality within their own police departments.”

The report authors note that while some mayors said they didn’t have control of reallocations, research conducted by the IoC five years ago suggests otherwise. In 2015, when only 5 of 87 responding cities had implemented body cameras, 93 percent of respondents said they supported the use of body cameras. By September 2020, IoC researchers found, 76 percent of cities had put this program in place. “What’s more,” the authors write, “the intensity of mayoral support for body cameras predicted whether or not the city implemented the reform. Eighty-six percent of cities in which the mayor strongly supported the reform saw the program implemented between 2015 and 2020, compared to 71 percent of cities where mayors were simply supportive. Only 17 percent of cities in which the mayor opposed body cameras ended up implementing the policy. Substantial political obstacles, rather than a lack of power, may prevent mayors from tackling more structural reforms to their police departments.”

IoC codirector Katharine Lusk says the survey results suggest a need for major evidence-based education efforts—alongside public pressure—to help mayors better understand the role racism plays in police violence. “It’s also important for more mayors to share their own stories of reform,” says Lusk. “In our interviews, we heard from mayors who had instituted major reforms and others who were innovating in important ways, including those implementing new crisis response units that include social workers and community members their residents trust. Others had used school closures to end contracts that brought police into schools. Peer leadership matters.”

The survey, one of four conducted in 2020 by the IoC, used a combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions to explore salient local issues and policy priorities. The three other surveys conducted in 2020 asked mayors about COVID-19 recovery and implications, parks and greenspace, and the 2020 US Census.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.