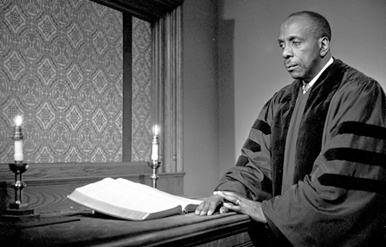

About Howard Thurman

Howard Washington Thurman (1899–1981) played a leading role in many social justice movements and organizations of the twentieth century. He was one of the principal architects of the modern, nonviolent civil rights movement and a key mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thurman grew up in Daytona, Florida and was raised by his grandmother, a former slave. As a child, Thurman complied with his grandmother’s request that he read the bible aloud to her, and he developed an interest in the text at a very early age. As a young child, Thurman also learned not only of the trials of slavery, but also of the slaves’ deep religious faith, which profoundly shaped his later vision of the transformative potential of African American Christianity. Thurman attended the Florida Baptist Academy in Jacksonville from 1915 to 1919, the year he matriculated at Morehouse College. In 1923 he graduated from Morehouse; he had purportedly read every book in the college’s library. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education in economics at Morehouse, he spent the summer of 1922 in residence at Columbia University, where he attended classes with white students for the first time. After receiving a bachelor of divinity degree from Rochester Theological Seminary in 1926, he served as pastor of the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Oberlin, Ohio. In the spring of 1929, Thurman studied mysticism at Haverford College under Rufus Jones, who was a Quaker. Mysticism came to figure prominently in Thurman’s theology. Indeed, Thurman evolved into a mystic who grounded all of his work in the idea that “life is alive” with creative intelligence.

During this period in the 1920s, Thurman was one of the most articulate and visible theological figures in the national student youth movement. As a regular on the YMCA and YWCA lecture circuits during the height of segregation, he was the student movement’s most popular speaker for interracial audiences. He was also a leading voice on the changing ministry of the Black Church. It was through Thurman’s experiences during this time that his faith in interracialism began to take root. In the late 1920s, Thurman became the first African American board member of the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). In this capacity, he urged his former student, James Farmer, to establish the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was a member of the organization’s board.

In 1929, Thurman returned to the South to serve as Professor of Religion and Director of Religious Life at Morehouse and Spelman colleges. This marked the beginning of his role as a forerunner in theological education at black colleges and universities, along with African American leaders Mordecai Wyatt Johnson, John Hope, Jesse Moorland, William Stuart Nelson, and Frank T. Wilson. During his tenure at Morehouse and Spelman, Thurman completed a series of sermons on Negro spirituals that would become the basis of the Ingersoll lectures that he delivered at Harvard Divinity School in 1947. He published these lectures as two books, Deep River (1945) and The Negro Spiritual Speaks of Life and Death (1947). In 1932, Thurman moved to Washington, D.C. to become Professor of Religion at Howard University, where he was appointed the first Dean of Rankin Chapel in 1936. Also during that year, he became the first person to lead a delegation of African Americans to India to meet with Mahatma Gandhi.

During the 1940s, Washington, D.C. was the center of the civil rights struggle in the United States. Also during this time, African Americans garnered some political influence in the federal government through the “Black Cabinet” and through New Deal programs that were established to address black economic concerns. Howard University intellectuals were in the forefront of this activity as advisors and agitators.

In 1943, A.J. Muste of the Fellowship of Reconciliation invited Thurman to recommend a student to help establish and co-pastor the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples (Fellowship Church) in San Francisco—the first major interracial, interfaith church in the United States. To Muste’s surprise, Thurman offered to co-pastor the church. Thurman’s ministry at Fellowship Church (1944–53) was deeply influenced by his experiences in 1935–36 while traveling in India, Ceylon, and Burma, particularly his meeting with Gandhi. Through the establishment of Fellowship Church, Thurman brought together people of different faiths, races, and classes in common worship and fellowship. This church has been designated as a national historic landmark for its creative ecclesiology and pioneering social vision.

The Gandhian ideas that Thurman developed in the years just before and during his tenure at Fellowship Church received a larger audience through the publication of his most famous work, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), which deeply influenced leaders of the civil rights struggle. In this work, Thurman offered the vision of spiritual discipline, as against resentment, that later informed the moral basis of the black freedom movement in the South. During these years, while serving on the boards of FOR and CORE, he regularly advised leaders of these organizations—including Martin Luther King, Jr., Pauli Murray,Vernon Jordan, James Farmer, Whitney Young, and Bayard Rustin—about matters both political and spiritual, always preferring quiet counsel and intellectual guidance to political visibility.

The years at Fellowship Church prepared Thurman for what was to be another daring adventure in his search for common ground among people of all faiths. In 1953, at the invitation of Boston University President Harold Case, Thurman resigned as Minister-In-Residence of the Fellowship Church to become the Dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University. Thurman was the first African American to hold such a position at a majority-white university.

Copyright © 2016, 2017 by The Howard Thurman Papers Project. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.