Panel of BU Experts Discuss the Global Climate Crisis

Researchers share their work on equity, climate change mitigation strategies, health effects, and more

According to a recent U.N. Report on Climate Change, scientists are observing unprecedented changes in the Earth’s climate. Immediate action is necessary, and efforts require collective, bold action on a global scale. That was the topic a panel of BU researchers examined during International Education Week’s Faculty Panel on the Global Climate Crisis.

The panel included Cutler Cleveland, Associate Director of BU’s Institute for Sustainable Energy, and Professor in the Department of Earth and Environment; Dennis Carlberg, Associate Vice President of University Sustainability, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in Earth and Environment; Madeleine Scammell, Associate Professor of Environmental Health in SPH; and Patrick Kinney Professor of Environmental Health in SPH. Science Journalist and WBUR’s Senior Producing Editor Barbara Moran moderated the discussion.

Held on the heels of the 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in Glasgow, Scotland, the IEW panel event drew a crowd of faculty, staff, and students who were eager to ask the researchers about their thoughts on the international conference, among other pressing climate issues. The panelists agreed that while some progress was made, the change is too incremental. Stronger, bolder action is needed urgently.

Summarizing some of the high points, Cleveland said, “Overall, there was some good news: Fossil fuels were ‘named;’ a lot of countries, including the U.S., strengthened their commitments to reduce emissions; and there was strong commitment, including by Brazil, to cut deforestation by 2030. 450 banks and international lending institutions agreed to make their asset portfolio carbon neutral by 2030…and 100 countries signed on to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030.”

Illuminating some of the gaps, Cleveland added, “I think the worst news was on the equity front.” He explained how developing nations and island states who are especially vulnerable to rising sea levels wanted to create a loss and damage fund where wealthy, developed nations would pay to help developing nations adapt to, avert, and minimize loss and damage from climate change. Talks of establishing such a fund did not move beyond the dialogue phase.

“It’s frustrating not to see more rapid action,” Kinney said. “I can understand, because politically it’s very difficult, especially between countries, so it’s understandable but it’s also unconscionable in a way because of what we’re facing.”

For years, scientists have clearly defined and modeled the earth’s temperature changes that will happen if climate policies are not implemented and followed. Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, the U.S. and 196 other countries pledged to limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels, and to also “pursue efforts to limit warming” to 1.5 degrees C.

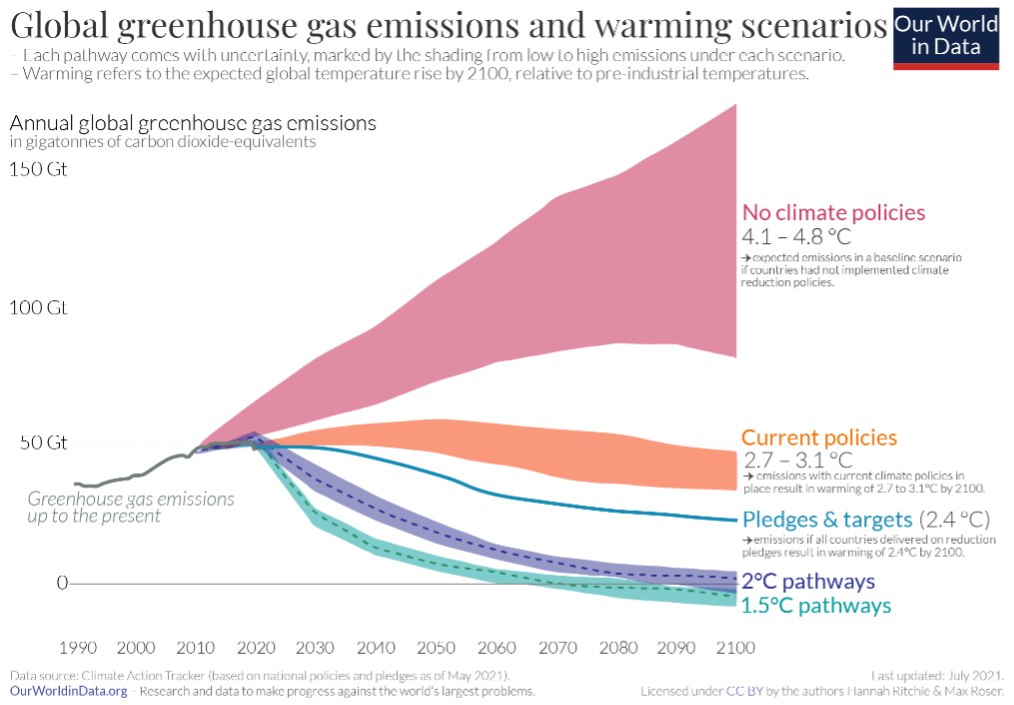

Cleveland walked attendees through this chart from OurWorldinData.org that projects how climate policies can abate greenhouse gas emissions, based on assumptions about economic activity, population growth, technological changes, and more. If no climate policies were put into place, the earth’s temperature would rise by ~4 degrees C, where irreversible and catastrophic changes would occur.

“The last major climate conference – from which came the Paris Climate Accord – said we should limit global warming to below 2 degrees C,” explained Cleveland. “If we really want to avoid the worst effects of climate change we keep [the warming] to 1.5 degrees C or less. With the current policies, we were on track for about a 2.7 degrees C increase. Most countries did increase their commitment to reduce emissions at Glasgow, and that would put us at about 2.4 degrees C. The good news is there were a lot of new commitments, but we’re not on track to reach 1.5 degrees C.”

In addition to COP26 and the urgent need to invest as much as we can in equitable climate solutions, the panelists discussed some of the health effects of climate change.

“We’ve found that the number of people who die each year from extreme heat is higher than deaths from other weather-related events,” Kinney said. “Often they are elderly, children, or people working outdoors.”

Scammell added, “They call heat the silent killer…and it’s not experienced equally by people.” She explained that undocumented workers, people who work outside, and agricultural workers are more susceptible and that they are often disincentivized to slow down when working in the heat.

Scammell is principal investigator a longitudinal study of agricultural workers in El Salvador. She is also studying occupational risk factors – such as extreme heat – of kidney disease in both El Salvador and Nicaragua. These efforts are focused on identifying and preventing exposures that may contribute to the epidemic of chronic kidney disease in Central America.

On the issue of health, Kinney explained how there are health benefits that can be captured as cities achieve their carbon reduction goals in the face of climate change. Moreover, there’s an opportunity for Boston and Massachusetts to be a leader in this.

“I was encouraged when looking at [Boston Mayor] Michelle Wu’s transportation platform to see how strongly she supports bicycling infrastructure,” Kinney said. “Boston could be more like Copenhagen or the Netherlands with bike highways that allow people to commute safely. Those bike paths get shoveled before the roads do. We could reduce a lot of carbon emissions and improve cardiovascular health… If you have political will you could put the resources where they are needed. And, as we’ve been saying, to do that in the most equitable way possible. It’s not just about biking – it’s about public transportation and green space.”

On the topic of infrastructure, Carlberg walked attendees through the incredible opportunity and need that exists to focus on adapting or retrofitting buildings and reducing building emissions. He noted, “In Boston, two thirds of our greenhouse gas emissions are from existing buildings.”

He explained that this fall the Boston City Council approved an ordinance that addresses climate change by requiring all buildings larger than 20,000 square feet to eliminate carbon emissions by 2050. He also showed BU’s newest building under construction: the Center for Computing & Data Sciences, which is the largest fossil fuel free, carbon-neutral building in Boston.

“It is 350,000 square feet and 19 stories, but there’s no gas line connected to this building; that is incredibly bold!” Carlberg said. “This is serious leadership that the university is bringing to the city, and the city is supporting and sharing what we’re doing with other developers who are building.”

Carlberg explained how the building will be heated and cooled by using the thermal mass of the earth.

For all the urgent and long-term work that exists in the areas of climate change mitigation or reduction and related areas, projects like the BU Center for Computing and Data Sciences should give people some hope that progress is being made and there are many brilliant minds dedicated to one of the world’s more pressing challenges of our time.

Watch the full panel discussion on the Global Programs site here.