When the Record Lies

How Forged Artifacts and Misinformation Are Rewriting Truth

How Forged Artifacts and Misinformation Are Rewriting Truth

In an age where chatbots confidently cite studies that never existed, fake news permeates social media, and scholarly opinions are met with distrust, the implications of misinformation has never been more palpable.

So what does that mean for published information that has been proven false?

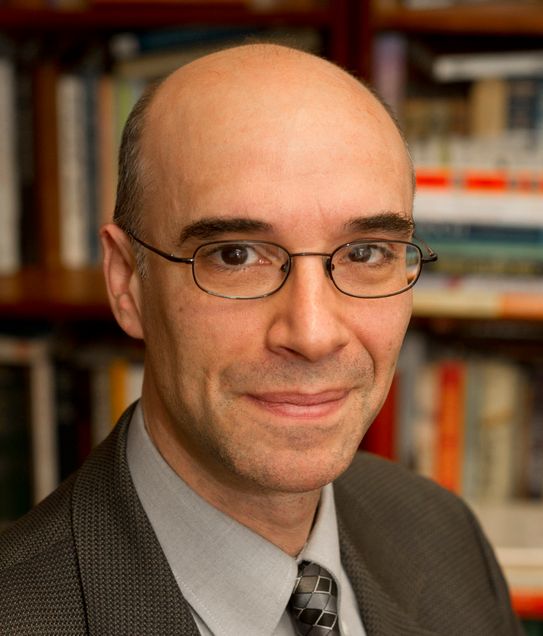

For Professor of Religion and Jewish Studies Jonathan Klawans, longstanding uncorrected publications of forged Dead Sea Scroll fragments led him to worry about the impacts on generations of future students and scholars.

These fragments, which surfaced after 2002, were authenticated by esteemed scholars and published in respected, peer-reviewed academic venues. But by 2020, scientific testing and subsequent admissions revealed that many of these recently discovered fragments were in fact modern forgeries. Still, most of the publications presenting these fragments remain uncorrected and available for purchase.

In a recent position paper, Klawans argues that retraction is an appropriate and necessary step to correct the academic record.

“At some point it occurred to me: why are these publications still for sale? That is a huge element of why I published my article,” says Klawans, who published “The Case for Retraction of Academic Authentications of Forged Fragments” in late-May in Ancient Jew Review.

“People who aren’t scholars of Dead Sea Scrolls are not ‘in the know’ and can easily be fooled because of the lack of self-correction.”

Prior to the publication of his piece, only one major volume—published by Brill in 2016—had been formally retracted and watermarked as such. Others, including Bloomsbury’s Gleanings from the Caves, continued to circulate, without any warning, even though the volume’s own editors have acknowledged that nearly half the fragments they published are fake.

Klawans’s article is not about uncovering new forgeries. The inauthenticity of these fragments has already been established through some scientific testing and scholarly consensus. What’s missing, he argues, is accountability. Most of the publications that presented these forgeries as authentic remain uncorrected, unmarked, and in some cases, still for sale. Klawans calls for formal retractions of these flawed works that lack elements of self-correction, not to punish authors, but to protect the integrity of the scholarly record.

“I’m really interested in academic authentications of forgery. I’m interested in having scholars look at these instances when we messed up—when things got through peer review that should never have,” he says. “I think many Dead Sea Scrolls scholars thought this story was just over. But it is not old news—there is unfinished business.”

This lack of transparency mirrors a growing concern in the digital world: the persistence of misinformation in AI-generated content. Just as forged scrolls can mislead scholars and students, AI systems trained on flawed or outdated data can confidently present falsehoods as fact. The difference is scale—AI can amplify errors across millions of interactions in seconds.

Klawans’s academic journey has long been shaped by questions of authenticity, but the issue came to the forefront of his work only more recently. His first book focused on purity, the second on sacrifice, and the third on Josephus and theological diversity in the Second Temple period. Each project hinted at the next, culminating in his current focus on forgery.

“Forgery is the way you fake antiquity, and literary forgery is often a response to the charge of heresy,” he explained. “That’s one of the ways I got into my current interest in forgery.”

His investigation into the Dead Sea Scrolls forgery crisis deepened while writing a book on biblical forgeries. What he found was troubling: a pattern of scholarly rationalizations—“broken pens, old scribes”—used to explain away inconsistencies in the fragments. And a publishing ecosystem that, in many cases, failed to acknowledge the possibility of forgery at all.

“I got more and more frustrated at how hard it was to do the work, but also at how many of these publications lack any elements of self-correction,” he said. “They don’t speak about the possibility of forgery; they just presume authenticity.” Klawans is careful to distinguish between academic disagreement about authenticity (which is par for the course) and publications that presume authenticity without argument. Retraction, he argues, should be reserved for the latter: when authenticity is presumed regarding objects that turn out to be fake.

“This is a very specific case,” he said. “I can’t think of other instances in the last 20 or even 30 years when things that turned out to be fake were published with hardly any discussion of authenticity whatsoever.”

His call to action is clear: follow the example set by Brill, the only major publisher to retract a volume of forged scrolls. Make the retracted content freely available, clearly marked, and accompanied by notices that explain the reasons for retraction.

And, he said, it is working—slowly. In June 2025, shortly after Klawans’s piece appeared in Ancient Jew Review, he forwarded the link to editors at Bloomsbury. Rather quickly—albeit after some back and forth—the publisher posted a “warning label” online for one of the forged scroll publications: “The Publishers were made aware that some of the fragments discussed in this book have been discovered, since publication, to be of dubious authenticity. The Publisher is investigating this matter.” At least one other similar warning has been posted with regard to another publication. And Klawans said a few other journals are also exploring the matter.

“I’m gratified that people are paying attention,” Klawans said. “I think there’s increasing recognition that there’s some unfinished business here—that it’s time to mark these fakes as fakes at the source.”

In November 2025, Bloomsbury formally retracted Gleanings in the Caves. The PDF is now available for free online, introduced by the publisher’s statement of retraction.