This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers. Certain seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear, and when the land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to live.

Pecola Breedlove, the protagonist of Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye, believes she would be beautiful if only she had blue eyes. With one brutal scene after another, Morrison gradually reveals how an 11-year-old Black girl could come to consider herself ugly; how she could conclude that not every flower can thrive in this land.

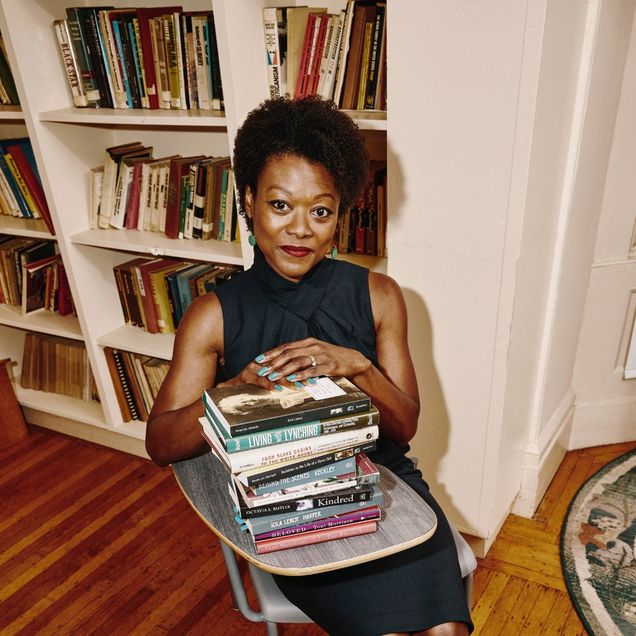

“That book exploded everything,” says Koritha Mitchell, who read The Bluest Eye in college. “It showed me that the experiences that I’d had up until that point were not simply because I was Black—it was because I was Black at the same time that I was not a man.”

“That book exploded everything,” says Koritha Mitchell, who read The Bluest Eye in college. “It showed me that the experiences that I’d had up until that point were not simply because I was Black—it was because I was Black at the same time that I was not a man.”

Mitchell, a professor of English, grew up in Sugar Land, Tex., where she recalls reading one white author after another in school. A Malcolm X poster hanging in her high school provided an isolated hint of African American intellectual achievement. It bore his quotation: “Education is our passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to the people who prepare for it today.”

When Mitchell read Morrison’s work in a women’s literature course at Ohio Wesleyan University, she discovered a book that reflected her lived experience—and she encountered, for the first time, Black writing that commanded study and celebration. She had thought her dream job would be editing Essence magazine, but The Bluest Eye steered her toward academia.

“The novel felt like it had been written for me,” she wrote years later, for an anthology devoted to Morrison. “[It] equipped me to see that assumptions around race and gender animate interactions in everyday life.”

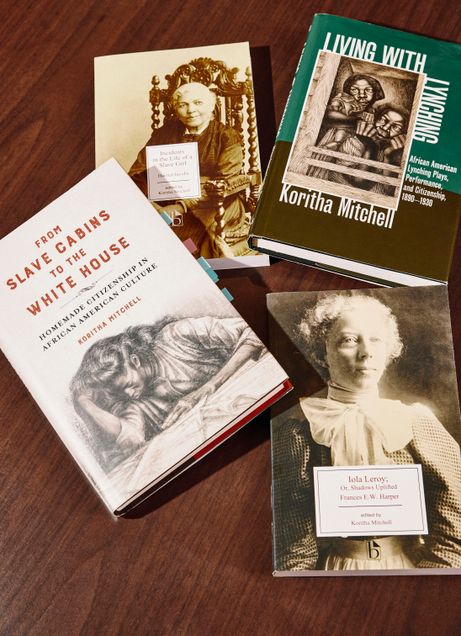

Mitchell takes an expansive view of literature, and her writing explores how injustices have shaped narratives throughout history—and persist today. She’s studied 19th-century slave narratives and novels, early 20th-century plays, and modern public personas. For her book From Slave Cabins to the White House: Homemade Citizenship in African American Culture (University of Illinois Press, 2020), Mitchell studied works by and about Black women—from Harriet Jacobs to Michelle Obama—to show how they’ve used success to define their place in a country that has often violently opposed their presence. “It’s my job to highlight what dominant culture doesn’t want us to notice,” she says.

Mitchell’s résumé extends well beyond her scholarship. She’s a cultural critic, public speaker, podcaster, and frequent contributor to mainstream media outlets. Her concept of “know-your-place aggression” has entered the public vernacular, appearing in stories published by, among others, Esquire, Teen Vogue, and FiveThirtyEight. The Women’s Media Center has honored Mitchell with its Progressive Women’s Voices IMPACT Award.

Her work transcends academia for a simple reason, says Vincent Stephens, BU’s assistant provost for faculty development and success. “People tend to think that humanities are antiquated. It takes a certain kind of mind to be able to say, ‘No! We can see patterns—let me take you back in history and then bring you up to speed.’ Koritha’s ability to bridge those gaps is really impressive.”

Know-Your-Place Aggression

In her first book, Living With Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citzenship, 1890–1930 (University of Illinois Press, 2011), Mitchell put forward a theory that has become a hallmark of her work. “Black folk are not always protesting so-called dominant culture,” she says—even though that’s been a critical lens often applied to everything from slave narratives to hip-hop songs. “It’s not about protest; it’s about Black success.”

Lynching plays provided a perfect case study. Often referred to as anti-lynching plays—a label that immediately defines them as against something—they highlighted the violence that terrorized Black people in the early 1900s. In the scripts, often written by women, Mitchell saw attempts to celebrate Black families and communities despite the violence. “There’s a cause-and-effect relationship here, and we have it reversed,” she says. Rather than interpreting Black creative work as a response to racism, she considers racism to be a response to Black success.

Mitchell’s phrase for this is “know-your-place aggression” and, more than a hundred years later, she sees examples of it every day: when Congress threatened to withhold funds from Washington, D.C., until the city destroyed a Black Lives Matter mural; when Maya Angelou’s memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, was removed from the US Naval Academy’s library; when federal agencies purged mentions of diversity, equity, and inclusion from their websites. The list goes on.

“I’ll just keep beating the drum because, unfortunately, the examples won’t stop coming,” she says. “I want people who are studying any marginalized group to focus on success, because that’s exactly what’s being erased.”

Disability studies and queer studies scholars are among those who have picked up her ideas. Her work is also resonating with a mass audience. In an Esquire magazine essay in April 2025, Mitchell S. Jackson wrote about Shedeur Sanders, a record-setting quarterback at the University of Colorado who was expected to be one of the first players picked in the NFL draft. Instead, he dropped to the 144th pick. “News flash: Shedeur didn’t fall,” Jackson wrote. “He was knocked down, pushed down, held down.” The media speculated about the reasons. Lack of humility? Cocky father? “A prime target of know-your-place aggression are Black people maligned as uppity,” Jackson wrote, crediting Mitchell for the idea. “How I see it, an uppity Black person is one who’s proven their excellence and reaped rewards for it.”

Mitchell identifies a corollary to know-your-place aggression: white mediocrity. When Black success is suppressed, mediocrity fills the void, she argues. “Violence is done when whiteness goes unmarked, when the unearned advantage just gets to sit there and not be questioned,” she says. “Our culture thrives on pretending that whatever is white and straight is neutral, and whenever anyone else achieves, a special accommodation must have been made.”

These insights emerge from a deep reading of African American literature, and a recognition of the patterns of violence and suppression evident in those stories. Twice Mitchell has published scholarly editions of 19th-century texts, recontextualizing stories written by Black women following the Civil War: first with Iola Leroy (Broadview, 2018), a novel by poet and activist Frances Harper, and then with Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Broadview, 2023) by abolitionist Harriet Jacobs. Mitchell sought to bring new attention to those classic books while situating the authors as predecessors to modern activists in the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements.

An Impactful Voice

Mitchell’s books might be academic, but she goes out of her way to make her work relevant to a broader audience. “I always want my ideas to be legible to the people I grew up with,” she says. “I want them to be able to see value in what I do. I want it to be useful to them.” Mitchell wrote about the forced resignation of Harvard University’s first Black president, Claudine Gay, for MSNBC, comparing her treatment to the way President Obama’s credentials, and even citizenship, were questioned. “They don’t need to have done something wrong for their opponents to believe they aren’t in their ‘proper’ place,” she wrote. She’s written a personal essay for Time about race, gender, and the standards for promotion in academia and an op-ed for CNN exploring parallels between the Netflix series The Chair and Iola Leroy—both of which feature women of color as protagonists. With this mainstream writing, Mitchell shifts her ideas from literature to current events, exposing how racist patterns of a century ago continue today.

“Koritha is someone who sees the bigger picture of how the public should be engaging with colleges, universities, especially at a very precarious political time,” says Stephens, who first met Mitchell in graduate school at the University of Maryland. “This is a moment where advocacy is very important.

Goodness and decency in a fundamentally violent culture requires deliberate action. It does not happen automatically.

In 2023, the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a nonprofit founded by Jane Fonda, Gloria Steinem, and Robin Morgan to promote women in media, recognized Mitchell with its Progressive Women’s Voices IMPACT Award. WMC board chair Janet Dewart Bell delivered a prescient introduction: “Right-wing leaders and organizations are actively working to repress Black history by banning books, erasing and whitewashing African American experiences, and targeting outspoken champions who articulate these truths. The politics of this moment cry out for the courage, insight, and analysis of the brilliant scholar Koritha Mitchell.”

Good and Decent

Another idea that Mitchell returns to often is “good and decent”—as in, a lot of people consider themselves good and decent by default, but they are not proactively fighting injustice. “Goodness and decency in a fundamentally violent culture requires deliberate action. It does not happen automatically,” she says.

Mitchell saw a glimmer of hope in the protests that followed the 2020 killing of George Floyd. “People of every background around the world were protesting,” she says.“That is a sign that you see somebody else’s humanity and you want to stand up for their rights.”

She considers the recent rejection of the diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts sparked by Floyd’s murder as nothing less than know-your-place aggression. “This administration is saying, ‘Oh, hell no, we’ve had too much of you seeing other people’s humanity, we’ve had too much of you thinking that they should have rights similar to your own,” Mitchell says.

“I have to believe that the brazen indecency of this moment will motivate people. I’ll keep beating the drum, hoping that more and more people will realize that we must all do better, and do more, on purpose.”