The World’s First Novel Has Romance, Tragedy, Adventure. Now, After 1,000 Years, The Tale of Genji’s Poems Have Joined the Digital Age

J. Keith Vincent, a CAS associate professor of Japanese and comparative literature, says the project was, in part, “a way to get students to slow down and pay more attention to the poems.” Photo illustration by Cydney Scott and Cheryl Skinn for Boston University Photography

The World’s First Novel Has Romance, Tragedy, Adventure. Now, After 1,000 Years, The Tale of Genji’s Poems Have Joined the Digital Age

BU scholar J. Keith Vincent and his students spent nine years building Genjipoems.org, a home to nearly 800 ancient poems

Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, often considered the world’s first novel, is many things: a seminal piece of Japanese literature, a groundbreaking work of female authorship, and an epic story of love, adventure, and betrayal. But beyond its celebrated prose, the 11th-century text is the source of hundreds of beautiful poems written by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the Japanese royal court, for her characters to deliver.

To J. Keith Vincent, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of Japanese and comparative literature, Genji’s poems are an often underappreciated part of the saga.

He hopes his latest project will help correct that: to give Murasaki’s poems their due, Vincent conceptualized and created Genjipoems.org, a first-of-its kind, interactive digital database of all 795 poems featured in The Tale of Genji. After almost nine years—and countless hours of work by both him and BU students—the archive officially launched this spring. Vincent debuted the database at the Association for Japanese Literary Studies annual conference.

But why focus on the poems?

In the Heian period, when Genji was written, it was common for people to communicate by sending or speaking poems to one another, Vincent says. Genji’s poems are written from the perspective of 118 different characters, from lovers and mothers to emperors and servants.

“It’s a really extraordinary feat to be able to ventriloquize all of these highly distinct characters and come up with the kind of poems that they would write,” says Vincent, also an associate professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. “Within 200 years of finishing her book, the greatest poets in Japan were saying, ‘It’s basically impossible to become a poet without having memorized The Tale of Genji.’”

It’s a really extraordinary feat to be able to ventriloquize all of these highly distinct characters and come up with the kind of poems that they would write

Or, as he writes on the site, “Spanning over a half-million words of prose, the Genji is one of the longest novels ever written. But the Tale is more than a novel. In addition to its 795 poems, the prose itself is spangled and braided throughout with highly allusive poetic language, constantly threatening to turn into poetry. Or rather, prose in the Genji threatens to turn back into poetry, since poetry is its source.”

And, yet, whenever he assigned Genji to his students in his classes, Vincent would frequently notice them skipping over the poems and their elaborate language to just read the prose. That’s where the idea for a database first percolated, Vincent says: “I thought of the project as a way to get students to slow down and pay more attention to the poems.”

Digitizing the Poems

The Tale of Genji is an account of court life in medieval Japan. The 1,300-page novel follows the titular Genji, a prince born to an emperor and his favorite consort, who goes on to amass great influence and have many love affairs.

Beginning in fall 2016, Vincent had his Japanese literature students find and input different translations of the poems into a spreadsheet for class assignments or extra credit. There are four primary English translations of Genji, and one translation of just the poems, which meant they had to type the equivalent of almost 4,000 poems, as well as the original Japanese versions; it took an estimated 150 students about six years. (The process could’ve been automated, Vincent acknowledges, but he felt the shortcut would have robbed his students of a close intimacy with the poems.) Along the way, Japanese literature and computer science students helped turn the translations into a basic website. Then, starting in 2021, multiple students, including Marshal Dong (CAS’23), Bryan Teoh (CAS’25), and William Zeng (CAS’25), received Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) grants to work on the website and “bring it to the next level,” Vincent says.

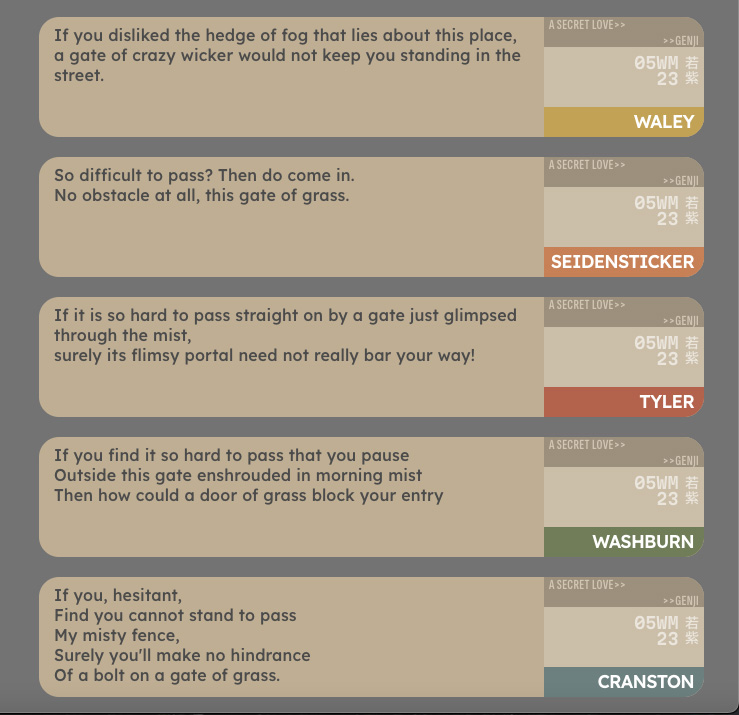

Over the past academic year, Vincent and his undergraduate thesis advisee Chris Ellars (CAS’24, CFA’25) populated Genjipoems.org with additional content, such as information on the characters featured in the tale. Ellars also wrote a biography of Arthur Waley, whose translation turned a century old this year. The four other translators are Edward Seidensticker, Royall Tyler, Dennis Washburn—a Dartmouth College professor and friend of Vincent’s who helped fund the website—and Edwin Cranston.

Screenshots of Genjipoems.org showing the poem page for the 23rd poem in chapter 5, a poem sent in reply to Genji from a secret admirer. Photos courtesy of Genjipoems.org

“It’s extraordinary how different the versions can be, how different the [translators’] styles are,” Vincent says. Even if a reader can’t understand the Japanese version—which is listed across the top of each poem page—“the idea is that you get a sense of the choices one has to make as a translator, and can gradually arrive at the nexus of the original [meaning] through these five different versions.”

The home stretch took place during the spring 2025 semester, when Vincent’s partner Anthony Lee, who runs the design firm Honest Struggle, created a colorful look for the database based on a series of famous 17th-century paintings that depict scenes from Genji. UROP student Shen Liu (CAS’25) helped implement the design, along with Wai Lun Mak (CAS’25) and Jason Huang (CAS’26).

The final result?

A comprehensive guide to each poem, complete with a checklist of information: the chapter and order of the poem, who the poem is delivered by and to whom, what form the poem is in (written, spoken, in reply to another poem, a group composition), what literary techniques Murasaki employs in the poem, whether the poem alludes to another poem in Genji, what season the poem is delivered in, and how old Genji is when the poem is delivered. Each poem page also has tabs for further details, such as analysis and discussion among site users.

“This was a massive undertaking,” Vincent acknowledges, laughing. “My God, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of hours went into just uploading the poems.”

But it accomplished exactly what he hoped it would.

The project provided many different ways for students to interface with Genji and its poems. Typing out translations, coding the website, mapping out the timeline—“every level of engagement was possible,” Vincent says. “And because the end result was public-facing, you felt like you were contributing to more than just a class assignment.

“My students were just amazing. I’m so grateful for the work that they did.”

An Evolving Tool

Genjipoems.org was always meant to be interactive: users, for example, can annotate poems and start discussions on poem pages. And as they go through a poem line-by-line, Vincent says, users will have “to pay very close attention to the words and notice things about them. By the time you get to the ‘write a commentary’ part, you have all the building blocks you need to write a sophisticated close read.”

That’s always been his goal, Vincent reiterates.

By participating in the site, it means readers “have slowed down, really read a poem, and not just skipped over it because they want to find out what happens next in the story,” he says. And, every time someone contributes to the site, it helps even more readers gain appreciation for Murasaki’s language—no matter how many more hours of work that entails.

“This project will never be done—and that’s great,” Vincent says. “That’s the best part of it.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.