As a Connecticut reporter working for the Hartford Courant in the 1970s, Dick Lehr infiltrated a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan as it recruited new members. Attending a meeting, he was struck when the Klan screened The Birth of a Nation, the landmark 1915 movie that pioneered modern filmmaking—while also putting a racist spin on post–Civil War Reconstruction. Director D. W. Griffith’s opus includes such scenes as a white woman throwing herself to her death to escape a leering black pursuer and the KKK riding to the rescue of a southern town in a state run by corrupt black leaders.

“That’s a thing that has always stayed with me,” Lehr says. “The Klan certainly understood its message of racism and hate and the demeaning portrayal of blacks.” Yet he’d first encountered the film in college, where students study how Griffith used the then-new medium of film to tell a lengthy (three-hour) narrative with a tapestry of characters, spectacular scenes of war, and innovative photographic techniques that became staples of moviemaking.

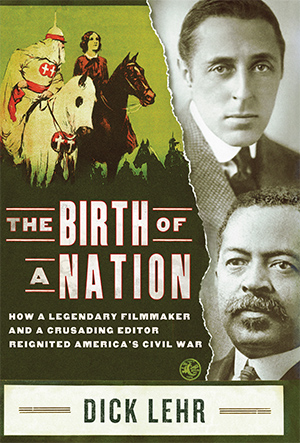

Lehr recalled his Klan run-in a few years back, when, as professor of journalism at the College of Communication, he stumbled across an article about Boston editor Monroe Trotter, an African American who tried to suppress Griffith’s film when it debuted in Massachusetts. He’d never heard of Trotter, whose confrontation with Griffith a century ago as editor of the Boston Guardian, an African American newspaper Trotter cofounded, is the topic of his new book, The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Filmmaker and a Crusading Editor Reignited America’s Civil War (PublicAffairs, 2014).

The coauthor of Black Mass: The Irish Mob, the FBI, and a Devil’s Deal, the book (and soon-to-be movie about gangster Whitey Bulger), Lehr was intrigued by Trotter’s in-your-face activism against the film, which included public protests and a failed attempt to persuade Massachusetts politicians to ban the film. Trotter died in 1934.

Bostonia interviewed Lehr about his new book.

Late in life, director D. W. Griffith appeared to regret his early racism. Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Bostonia: After writing about Whitey Bulger, what made you interested in Birth of a Nation?

Lehr: They’re [both] stories that go to a bigger theme. I’ve always been interested in justice and injustice, abuses of government power, civil rights. Four or five years ago, I was reading an article that made a reference to the Boston civil rights activist and newspaper editor Monroe Trotter, and I went, huh? I’ve worked in Boston a long time; how come I don’t know this guy’s name? I started reading about him. In the early 1900s, he was famous. Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Dubois would be mentioned in the same breath. I wanted to rediscover him.

I saw that in 1915, when Birth of a Nation came out, Trotter was at the forefront of what turned out to be this amazing protest in Boston against [it] that went on for over three months. The other complication that I think is fascinating is how could a newspaperman, a First Amendment guy, [seek to] limit the expression of speech? Trotter and Dubois were conflicted. They were kind of the free speech guys. They tried to fight speech with speech, which would have meant their own movie, but they couldn’t finance it. So, in the end, they resorted to the tools in their toolbox. At the time, censorship was not demonized like I think it is today.

In the end, did Griffith have the last laugh, in that his film is remembered and continues to be studied in film programs, while Trotter seems to have been largely forgotten?

I’m not sure. In civil rights circles and black America, he is not forgotten. There’s a national organization of black columnists called the Trotter Group. There’s a Trotter elementary school in Boston. There’s a Trotter Institute at UMass Boston.

Later in his life, Griffith had an epiphany that the movie was racist and should not be shown. What was behind that?

I can only speculate. Was it because a lot of time had gone by? He was older, wiser and had a broader understanding of civil rights?

Fresh off writing about gangsters, Dick Lehr pivots to a racially charged film fight in his new book. Photograph courtesy of PublicAffairs

You write that some academics in 1914–1915 claimed blacks were inferior to whites. The people I would have expected to stand up with Trotter, highly educated professors, you say were actually working to suppress civil rights. Do you draw any lessons from that today?

Racists were relying on science saying that the [African American] brain was smaller than the white man’s brain. It makes you realize that whether it’s conventional wisdom or certain schools of thought, it’s a test of time, whether things do take root and become the truth. But boy, it was pretty powerful stuff at the time that justified a whole lot of racism.

“Negro” is a term that has fallen out of use. In this book, you use it. I wonder if some readers might be taken aback by that?

I wanted to use the words of that era, because I find it jarring in the narrative to say “African American” or even “black,” or terms that are more current. I’m trying to put people in the moment in a dramatic narrative. I also thought about how the terminology is fluid and it changes. Even Trotter, early on, says “Negro” but later on preferred “colored” or “colored American.”

Great research and work by Dick Lehr! Of course, William Monroe Trotter is definitely NOT a “forgotten journalist”! There is ample historical evidence and journalistic assessment of Trotter and others, who challenged Booker T. Washington, and then were punished for it. As a graduate of Boston University’s class of 1984 Afro-Journalism Program, we learned about Trotter and several other members of the “Black Press”–perhaps it’s time to revive the Afro-Journalism degree!?