All week long, Americans are commemorating the anniversary of one of the most influential speeches in history, a speech that set the stage for sweeping changes in American society—and a speech given by a BU alum.

It was 50 years ago this Wednesday when 250,000 people converged on the nation’s capital to take part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Their goal was to push for full civil and economic rights for African Americans. People arrived by bus and by car, by train and by plane, many traveling for days—and at great personal risk—to be part of what would be the largest peaceful demonstration in US history.

Despite fears that the crowd might turn violent (the Pentagon had 19,000 troops on hand in the suburbs, and in anticipation of casualties, area hospitals canceled elective surgeries for the day), the huge throng remained orderly as participants marched from the Washington Monument to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. There they listened as civil rights and religious leaders called for passage of civil rights legislation, an immediate end to school segregation, and the implementation of a $2-an-hour minimum wage.

Today, most of the day’s speeches have been forgotten, but one—the last of the day—affected the course of history.

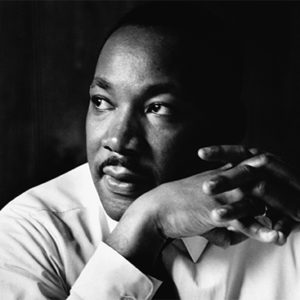

Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) addresses marchers during his “I Have a Dream” speech on Aug. 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo by AP

When Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) rose to stand before the bank of microphones, few could have imagined that the words he was about to speak would resonate five decades later. King, the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, reportedly did not know until the day before what he would include in his speech. He began by recalling that 100 years earlier, President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and he reminded the crowd, and the millions of Americans listening on radio and watching on television (all three networks carried the proceedings live), that the country’s founding fathers had based the Declaration of Independence on the premise that all men have the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. King went on to speak of the promissory note still owed to African Americans, saying that the country had delivered a bad check, marked insufficient funds. His voice soaring, he told the crowd that it was time to “cash this check—a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

It was a good speech, but something remarkable happened, transforming it into a speech for the ages. At one point King reportedly feared he was losing his audience, and at that moment, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson whispered to him, urging him to tell the crowd “about the dream.” King took her advice. He went off-text, and for the next six minutes his words held millions of Americans spellbound. Eight times, he repeated the phrase “I have a dream,” most poignantly when he spoke of having “a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

King’s plea for an American dream that would extend to all citizens, regardless of race, is credited with helping make possible the passage, one year later, of the landmark Civil Rights Act, followed in 1965 by passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Now, 50 years later, the nation celebrates the anniversary of King’s iconic speech with a series of events, highlighted by an address by President Barack Obama, to be delivered on Wednesday, August 28. Like King, Obama will speak from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, part of what is being billed as the Let Freedom Ring ceremony. Bells are scheduled to ring out in cities and towns across the nation that day at 3 p.m., commemorating the moment King began speaking.

To mark the anniversary, Bostonia reached out to faculty, staff, and students, asking them to talk about what King’s speech means to them today. Their answers are a reminder that his words continue to inspire, continue to serve as a source of hope for some, of solace for others.

Boston University and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

I was in the STH class of ’68 and want to share the impact of Martin Luther King on me and STH. In 1963 I was an undergraduate student in Florida, active in the Methodist Student Movement, and went to the summer regional MSM conference. From there, I was selected to be a delegate to go to the March on Washington. I recently wrote about that story and those who are interested can read about it on the website where I work at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro: http://cnnc.uncg.edu/2013/08/march-on-washington-august-28-1963/

For BU, I want to share about the follow up to the speech. It galvanized me to commit to civil rights, and I decided I wanted to go to BU School of Theology for graduate school, partly because Martin Luther King went there, and because STH had a reputation for being in the forefront of Christian Social Ethics at that time. I specifically remember in a class in Christian ethics and social reconstruction taught by Dean Walter Muelder, he would critique the role of King and nonviolence in the civil rights movement as a case in point. In a class taught by Dr. Peter Bertocci in philosophy of religion, I remember students asking questions on a couple of occasions, and Dr. Bertocci responding, saying that Martin had raised the same question a few years earlier, but he was sitting on the other side of the room at that time.

A student who was working in Dean Muelder’s office in the spring of 1967, told me that Dr. King came to visit Dean Muelder. The student said that Dean Muelder told her afterwards that Martin wanted to discuss the possibility of his running for Vice President on a special Peace and Freedom ticket in partnership with Dr. Spock who would run for President on the same ticket. Dr. Spock, a renowned pediatrician, was also a renowned peace activist. Dean Muelder reportedly advised King that they should not do it because it would just drain some votes away from the Democrats, and neither party would seriously try to pose an end to the Vietnam War.

On April 4 of 1968 the STH was hosting a play written and performed by STH students. During intermission, Dean Muelder came out on stage and said that the planned follow up discussion after the play would be cancelled because Dr. King had just been assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Classes were suspended for the next couple of days as students held teach ins and planned on how to help prevent Boston from being overwhelmed by riots in the aftermath of his death.