As It Turns 90, Social Security Is Showing Its Age. Boston University Economist Has a Fix

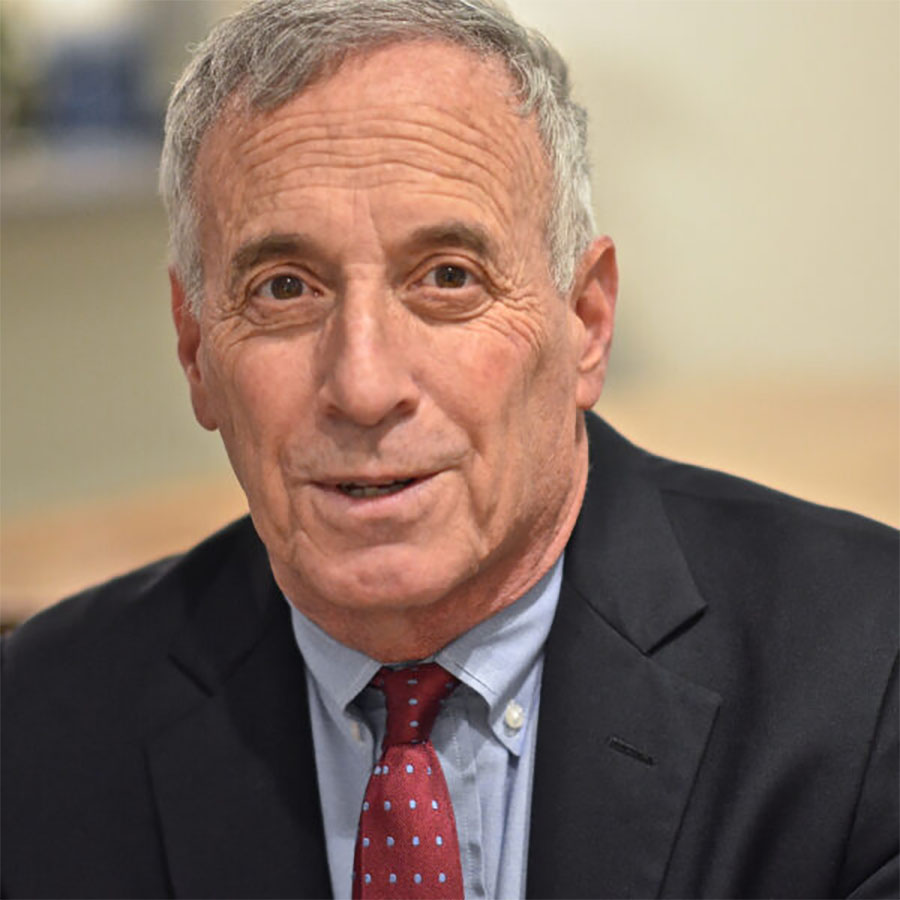

Laurence Kotlikoff discusses how to avoid insolvency and keep “essential” program afloat

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Social Security into law on August 14, 1935. Photo via AP Photo

As It Turns 90, Social Security Is Showing Its Age. Boston University Economist Has a Fix

Laurence Kotlikoff discusses how to avoid insolvency and keep “essential” program afloat

August 14, the 90th anniversary of President Franklin Roosevelt signing Social Security into law, marks both a historic milestone and a reminder of worrisome current events: a recent report by the retirement system’s trustees shows that it’ll run short of money in 2033, sooner than previously thought. That would result in millions of recipients taking a 23 percent cut in their monthly benefits, absent other changes.

President Ronald Reagan and Congress enacted reforms in 1983 that fast-tracked planned payroll tax increases, hiked taxes for wealthier retirees, and extended the retirement age, buying extra decades of solvency. But the changes weren’t enough, says Laurence Kotlikoff, William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor of Economics at Boston University’s College of Arts & Sciences, leading expert on Social Security, and coauthor of Social Security Horror Stories.

The program’s 90th birthday certainly bears celebrating, he says. “I think Social Security is essential,” Kotlikoff tells BU Today. “But it was put together in a hodgepodge manner through time, and all the problems associated with its design are haunting us. So it’s time to get Social Security fixed for good.” How would he do that, and how did the system’s financial problems accelerate? Kotlikoff, whose software tool Maximize My Social Security is offered free of charge to BU employees, gave his take.

Q&A

with Laurence Kotlikoff

BU Today: What factors advanced the program’s predicted insolvency to 2033?

Kotlikoff: Two things. One, a Social Security Fairness Act [signed by former President Joe Biden] extended benefit increases to lots of people who had worked most of their careers in noncovered [by Social Security] jobs—for example, being a teacher in Massachusetts. These people don’t have very long earnings records [in the Social Security system]. Because of that, the system looks at them and says, you’re poor, and the benefit formula says, if you’re poor, we give you a better deal. These people aren’t lifetime poor. They just didn’t spend their whole lifetime working for Social Security [benefits]. So that’s a big hit.

There were good proposals for how to do a better job on that, but it would have required the system to get information about the past earnings of all these [uncovered jobs]. It requires coordinating a lot of computer systems and collecting all of that. People in Congress saw the incompetence of the system—and, of course, it was Congress’ own fault for decades, underfunding the system and overloading [Social Security employees]. So Congress just decided, we’ve had enough angry telephone calls from constituents about this. We’re just going to say screw it.

We also have more pessimistic demographic projections and earnings growth projections. Part of that has to do with the share of wages that are covered by Social Security, which is going from about 90 percent going back years to about 80 percent today, because of wage inequality.

It’s time to get Social Security fixed for good.

BU Today: What do you believe is the best solution to avoid enacting benefit cuts?

The best solution is to do what the private sector did when they had their out-of-control, unfunded pensions in the ’80s. You pay off the accrued benefits under the old [Social Security] system, and then you set up a personal account system, where everybody’s money is contributed into their own account. It’s collectively invested—not by Wall Street—in a fully diversified manner. And then people get benefits out at old age in inflation-protected form, and as an annuity. The government contributes on behalf of the poor and the disabled, the unemployed, so it’s progressive. [Spouses’] contributions are divided and put in each account, so there’s contribution sharing.

BU Today: Is that different from 401(k)s? The retirement income they produce generally has not matched what private pensions used to provide.

[I’m] talking here about a [mandatory] 10 percent contribution and investing in the global market, which has historically earned a high return. In the 401(k) system, you have a lot of employees that don’t participate or don’t participate fully. The consequence is that there’s too little money going into the system, and then Wall Street is grabbing its chunks from [investment] fees. We’re set up to help Wall Street, in large part, make money.

If you look at a country like Singapore or Norway, where they have sovereign funds, I’m talking about that kind of a system. Something that involves no participation whatsoever by greedy bankers.

BU Today: The program’s insolvency is eight years away, and we’ve heard such alarms before. Why should we be concerned now?

I think everybody needs to think all the time about the future, look at worst-case scenarios, and plan conservatively. And my guess is that there will be cuts or higher taxes at some point—including higher taxes on Social Security hitting the wealthy—and there’ll probably be an expansion of the payroll tax [back to] 90 percent of the wage base.

The idea that there’s actually going to be a 23 percent cut in benefits on January 1, 2033—I think that’s really remote, but other things will have to adjust. This can’t go on, and they’re either going to make intelligent, fundamental reform or they’re going to kick the can some more down the road. We need about a 5.2 percentage point payroll tax hike, starting immediately, from [the current] 12.4 percent to 17.6, according to the trustees’ report, in order to pay the benefits that are scheduled.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.