BU Engineers Are Helping to Bring Semiconductor Production Back to the US

Researcher Ayse Coskun talks about how the University is well positioned to help the nation stay on top of chip technolog

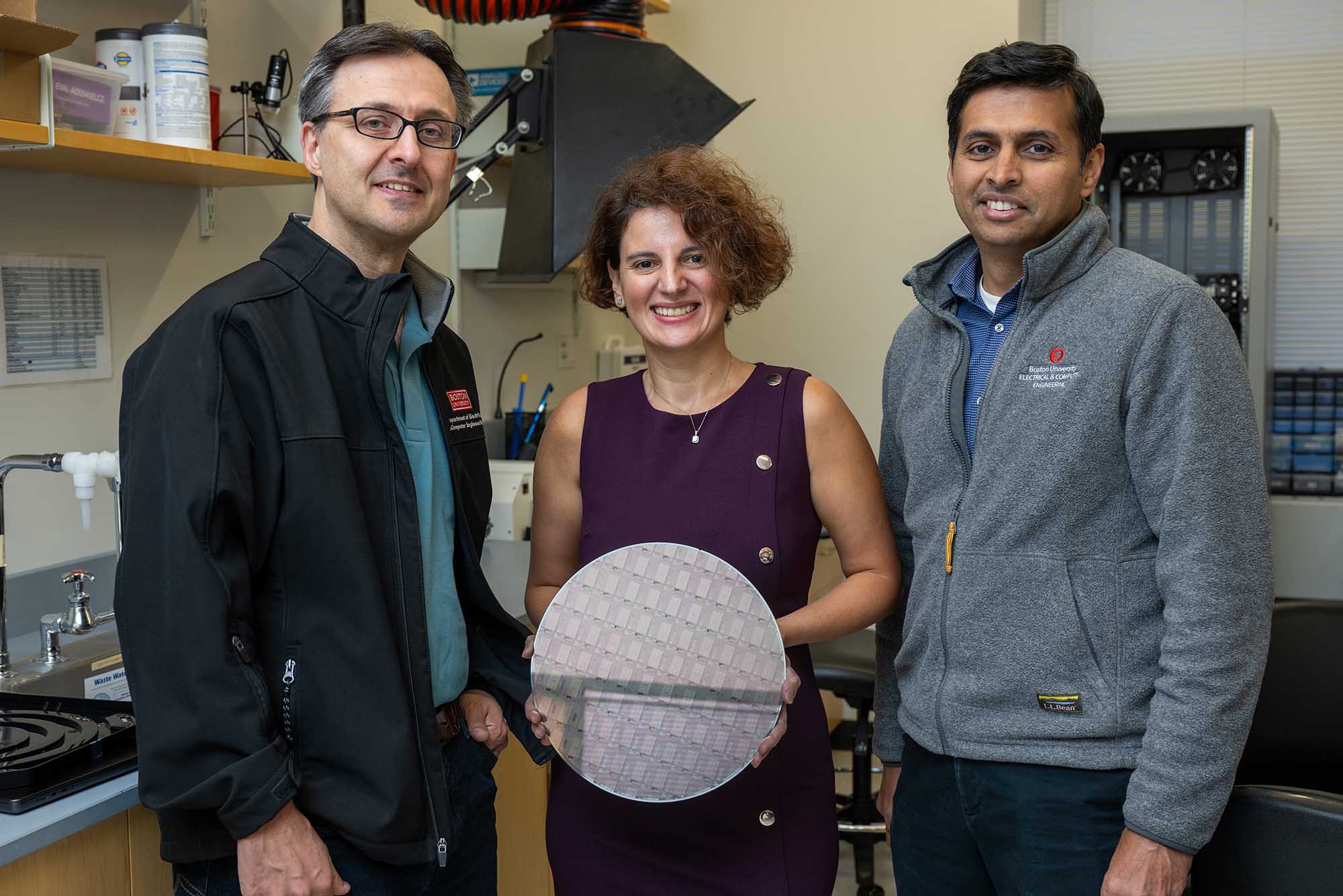

Boston University has launched a new website showcasing its semiconductor research. Photo by Cydney Scott

BU Engineers Are Helping to Bring Semiconductor Production Back to the US

Researcher Ayse Coskun talks about how the University is well positioned to help the nation stay on top of chip technology

At least one issue still unites many politicians across the aisle: the global race for dominance in the semiconductor industry.

The bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at boosting the US to the lead of that race, was signed into law in 2022. And though a great deal has happened since then, the federal government remains committed to bringing chip manufacturing home, says Ayse Coskun, a Boston University College of Engineering professor of electrical and computer engineering and of systems engineering.

She recently helped the University launch a new website showcasing its work to strengthen the nation’s semiconductor innovation and industry. Semiconductors are a crucial component in almost all modern technology, from computers to cars to medical machines.

The Brink spoke with Coskun, who is also ENG’s associate dean for research and faculty development and director of the BU Center for Information & Systems Engineering, about the importance of staying on top of chip technology—and how BU is positioned to help the US be a world leader in semiconductor production.

Q&A

with Ayse Coskun

The Brink: In one sentence, what does the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act do?

Coskun: Broadly speaking, the CHIPS and Science Act meets the need for the US to grow its technology research and workforce related to making the semiconductor microchips that underlie modern computing.

The Brink: Why is that important?

Coskun: Chips are everywhere, from smaller devices—like our personal phones and laptops—to the servers that run the data centers that are the backbone of everything we do today, from finance to healthcare to entertainment. Obviously, AI is becoming more pervasive, and the backbone of AI runs on chips. There are all kinds of applications.

So, the CHIPS and Science Act was put together to increase the competitiveness of the US chip technology sector, after years of outsourcing production to countries such as Taiwan. The goal was to cultivate more research and development here in this country, where the microchip industry began, and to boost the development of the workforce necessary to build circuits and chips.

The Brink: Where does Boston University come in?

Coskun: We already have a strong community of faculty working in circuits, bio-circuits for biotechnology and healthcare, and photonics to accelerate computing, among other areas; we’ve put together a new BU CHIPS website highlighting their contributions. So this initiative will amplify our efforts by bringing new funding and partnerships that grow our programs and create hands-on opportunities for students. The result is graduates who are not only ready to build impactful technologies, but also equipped to launch new innovations and start-ups—fueling a continuous cycle of discovery and impact.

The Brink: Does the federal government still consider the semiconductor industry a priority?

Coskun: There hasn’t been a major shift from the focus on advancing chips technology development and manufacturing in the US. In fact, reviving the domestic semiconductor industry has the distinction of aligning with the current administration as well as the previous one. The global pandemic disrupted the supply chain for chips, which was spread out around the world. A focus of the CHIPS and Science Act—which was a bipartisan bill—was to make it harder to interrupt that pipeline in the US. That aligns with the current administration’s focus on moving manufacturing to the US. Technology leadership means not only partnering across the globe, but also having the strength to design and build right here.

The Brink: You mentioned BU providing new hands-on experiences for students in this field. Can you give an example?

Coskun: Next year, Rabia Yazicigil [an ENG associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and of biomedical engineering] will be teaching the Build-a-Chip Boot Camp. Our chips classes have always been hands-on, in the sense that there’s always been a project component where students were designing integrated circuits using simulations. Now, there will be a “tape-out” component, which is the stage in chip design where you fabricate and test a prototype. It’s super exciting, because they’ll get to make a real chip.

The Brink: You also mentioned faculty who are already working on circuits, bio-circuits, and more. Can you tell us about some standout projects?

This plays to some of BU’s great strengths, such as bioelectronics, where the goal is to design hybrid systems that combine living sensors or other biological components with electronic circuits. There are applications in healthcare, environmental monitoring, and sustainable manufacturing. Rabia received an NSF CAREER grant to develop a secure, miniaturized sensor for monitoring human body systems—for example, gut health. It’s a complex task, because you need to make the chip tiny while ensuring functionality, you need it to consume power to do all the processing that’s needed, and you need the device to be secure, to make sure it’s not hacked. So you need innovation to design within all these constraints.

Another strength of BU is our flagship photonics program, and this has applications in chip design. We have one of the pioneers of silicon photonics, Miloš Popović [an ENG associate professor of electrical and computer engineering]. Miloš and his team have developed the world’s first scalable electronic-photonic-quantum chip, which is a key step toward quantum supercomputing. The chip was fabricated in a commercial foundry by the start-up he cofounded, Ayar Labs, which has become an industry leader.

Ajay Joshi [an ENG professor of electrical and computer engineering], too, has started a company, CipherSonic Labs, along with his former student Rashmi Agrawal (ENG’17,’23), to bring to market their novel chip that can process encrypted data 1,000 times faster than currently available methods. They developed this technology in part with support from the National Science Foundation.

The Brink: Is it safe to say this kind of innovation wouldn’t happen without federal funding?

Federal funding is essential. While research in the lab and technologies in industry may seem like separate worlds, they are in fact deeply interconnected parts of the same ecosystem. Research pushes the boundaries of what’s possible and drives the next wave of innovation, while industry brings those advances into real-world practice. When one part of this ecosystem is weakened, the rest cannot thrive. That’s why federal funding is so critical—not only for universities, but also for the companies that depend on new discoveries to grow and compete.

This innovation ecosystem is especially critical in the chip industry. The next generation of medical devices will all rely on electronics. The same is true for future AI data centers, entertainment technologies, and others. Any application you can imagine involves an electronic device to sense, measure, calculate, or provide feedback to the user. This “chips” research touches and shapes nearly every aspect of society.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.