Robert Pinsky, America’s Ambassador for Poetry, Retiring from Teaching After 36 Years at BU, More Than 1,000 Students

University will honor the award-winning poet and former US Poet Laureate Thursday, when he’ll do a public reading

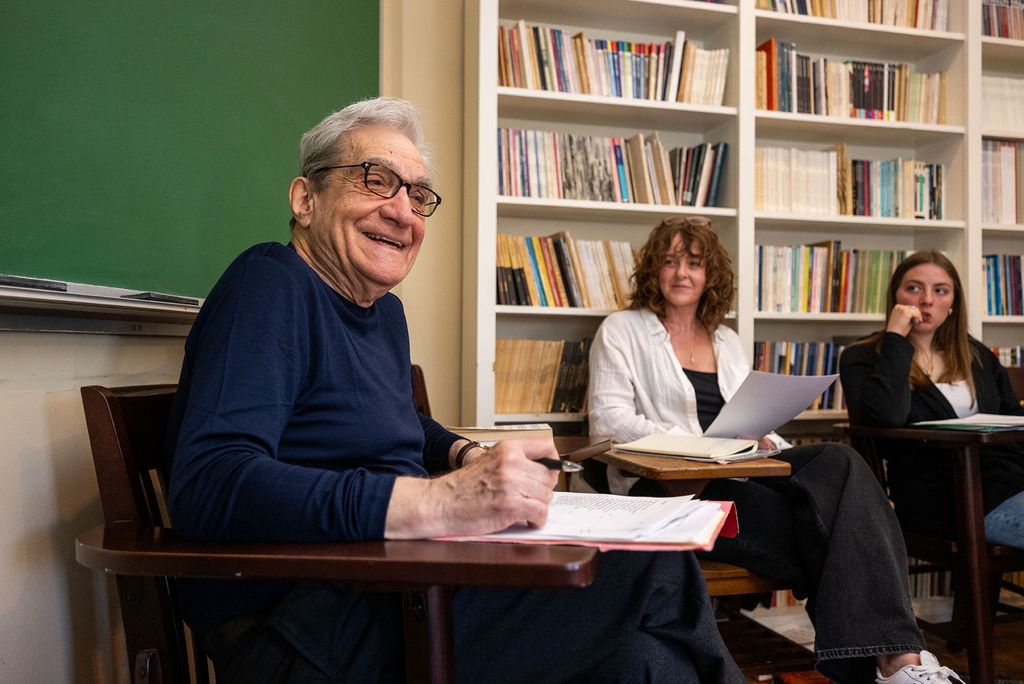

Robert Pinsky, who has taught generations of poets in BU’s Creative Writing Program, is retiring after more than three and a half decades at the University. “I’m satisfied with what I’ve done here…. I think, gee, this was awful good. It was a lot of fun.” Photo by Gabriela Hasbun

Robert Pinsky, America’s Ambassador for Poetry, Retiring from Teaching after 36 Years at BU, More Than 1,000 Students

University honored the award-winning poet and former US poet laureate on Thursday, when he did a public reading

On a recent Friday morning, a group of eight Boston University graduate students gathered in a circle inside a second floor room at 236 Bay State Road for Poetry Workshop II, a seminar taught by one of BU’s most decorated professors—and a former US poet laureate—Robert Pinsky.

Over the next few hours, they read aloud poems written by fellow classmates. Next, the poems’ authors read their work in their own voice, and the class then discusses the poem. And in keeping with tradition, one of the students reads aloud a selection from Singing School: Learning to Write (and Read) Poetry by Studying with the Masters, an anthology edited by Pinsky. On this day, Heather Wright (GRS’26) reads Louise Bogan’s “Women.”

It’s a scene that has been replayed every week since Pinsky arrived at BU in 1989 as a visiting lecturer, a return to the East Coast for the New Jersey native. He had come to BU from the University of California, Berkeley, for what he expected would be a yearlong appointment, but once settled in Boston, he found that he loved teaching in an MFA program (Berkeley had no creative writing program).

“The students [at BU] wanted to know exactly the kind of thing I’m interested in,” Pinsky says. “There was a door and on the door it said the words, “Creative Writing.”

More than three and a half decades later, Pinsky, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, is preparing to retire from teaching. By his own count he has taught roughly 1,000 students at BU, most of them in the graduate MFA program. And on Thursday, the University celebrated his legacy with a reading, where he read some of his own works at the Duan Family Center for Computing & Data Sciences.

In addition to being one of the most respected poets of his generation, Pinsky has used popular culture to champion the cause of poetry. He’s been invited to read poems on the PBS News Hour to mark major news events and celebrations, judged a “Meta-Free-Phor-All” contest between Stephen Colbert and Oscar-winning actor Sean Penn on The Colbert Report, performed with Bruce Springsteen, was poetry editor for Slate, and even guest starred in an episode of The Simpsons, where he recited his poem “Impossible to Tell.”

Former colleague and Nobel laureate, the late Louise Glück, once said of Pinsky, “[He] has what I think Shakespeare must have had: dexterity combined with worldliness, the magician’s dazzling quickness fused with subtle intelligence, a taste for tasks and assignments to which he devises ingenious solutions.”

Teacher and poet

Hours after his seminar class has ended, in his book-lined office across the hall from his classroom, Pinsky is, by his own admission, “in a somewhat elegiac mood,” as he recalls the many close friends he’s invited to BU to give readings over the years—including Nobel Prize winners Seamus Heaney and Glück, as well as C. K. Williams and Adam Zagajewski, all of whom have passed away.

But he smiles as he recounts the many amazing students he’s worked with, among them Pulitzer Prize winner Carl Phillips (GRS’93), Diane Mehta (GRS’94), and Erin Belieu (GRS’95). Even his seminar room—Room 222—has a notable history: it’s the room where poet Robert Lowell famously taught Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath.

“In the tradition of BU, they were peers of mine as well as students,” he says.

Pinsky says that the most essential thing he’s tried to impart to his students is the importance of consulting one’s ancestors. “You use the past. You do not worship it, you consult it…you are obliged not just to keep it alive, but to change it and contribute to it and adapt it and keep it alive by making it new.” Photos by Cydney Scott

Former students credit Pinsky with instilling lifelong lessons.

“I was in my mid 20s when I studied with Robert and was a fairly unruly creature at the time,” Belieu recalls. “Robert taught me many things—too many things to name here—but perhaps the greatest gifts he gave me were in teaching me how poetic invention comes from discipline, compression, a bracing and truthful lack of sentimentality—how one frees a poem into surprise, interesting thought, and vivid imagery through those rigors.”

Asked to name the most important lesson he’s tried to impart to his students, Pinsky digs deep into history for an answer. “To them and to myself I tried to emphasize the ideal I first heard in the Zulu culture in Africa—to consult the ancestors. You use the past. You do not worship it—you consult it. And one of the obligations to the poetry…you are obliged not just to keep it alive, but to change it and contribute to it and adapt it and keep it alive by making it new.”

He says he’s always stressed the importance of listening, which is one of the reasons he has his students listen to one another and listen to poems by masters like William Butler Yeats, Marianne Moore, Baudelaire, and Horace. In short, he encourages his students to read with their ears. For him, poetry is both a vocal and a bodily art.

“Poetry is uniquely and supremely able to get into the audience’s body. The words of the poem come alive, as I imagine saying them or actually say them. It is the most intimate, and in that sense, the most bodily of all the arts. As a teacher, I have tried to demonstrate that and encourage that great fact for the students.”

Every year, Pinsky asks his students to put together a personal anthology of poems. He urges them to type them so that they get the physical experience of seeing and hearing the poems. They’re asked to pull together a mix of historical and contemporary works. It’s meant to serve as a kind of autobiography that increases over the years, but the exercise also affords him some insight into what young poets are reading and the poets they’re drawn to.

He’s been keeping his own anthology for years, continually adding to it. The spiral-bound collection now numbers hundreds of pages and includes poems from Alexander Pope to Ezra Pound.

The author of 11 acclaimed poetry collections (the most recent, Proverbs of Limbo, was published last June by Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Pinsky has earned a reputation for poems that have a distinct musicality. A saxophone player in high school and college and a lifelong lover of jazz, he says that in his own work, music and poetry are “sister arts.”

“Every time I write a poem, I am thinking about some great ballad player like John Coltrane, but also going back to Lester Young. I think of the emotion that you get when you hear the same basic head melody or the basic chord progression again and it’s gotten richer or it’s changed, it’s done something different. That’s my model for feeling and excellence.”

In addition to his books, which he cites as his proudest achievement, he has also released three PoemJazz CDs, where he’s teamed up with a trio of gifted jazz musicians. As they play, he serves as vocalist, improvising as he reads one of his poems (or those of another poet), sometimes using a fragment of the poem as a refrain, other times beginning with the end of a poem and then circling back to its beginning.

“The musicians listen to me, and my voice is like another horn in the combination,” he says. “We are very much listening to one another and in concert together.”

Pinsky’s work has earned him numerous accolades, including the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America, a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from PEN. In 2015, BU named him a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor, the highest honor bestowed on senior faculty who are actively involved in research, scholarship, teaching, and University civic life.

A leading ambassador for poetry

Perhaps no poetry honor is greater than being named United States poet laureate, also known as poet laureate consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress. First appointed in 1997, Pinsky was the first person to serve three consecutive one-year terms. He used his newfound public stature to promote the importance of poetry in contemporary life. In addition to giving readings at the White House and across the United States, he launched the Favorite Poem Project, an initiative that invited Americans across the country and from all backgrounds and ages to read their favorite poem and to talk about why it resonated with them.

The project, largely nurtured by Pinsky’s former BU student Maggie Dietz (GRS’97), took off. Today, the archive includes an estimated 18,000 audio recordings and approximately 60 videos. Together, they make an eloquent case for the primacy of poetry in our everyday lives.

“I hoped it would contradict the cliché, or stereotype, that Americans, by and large, aren’t interested in poetry,” Pinsky says. Among the videos are a construction worker reading a poem by Walt Whitman, a glass blower reading a Frank O’Hara poem, and a Cambodian American student reading a poem by Langston Hughes.

“I didn’t expect the eloquence that people demonstrated,” Pinsky says. “It turns out, when you really like a work of art, you don’t need to be an expert…it widened my own range of responses to understand that when people truly love a work of art, their individuality can give insight into it. That is remarkable and worth attending to.”

BU’s Center for the Humanities recently announced that as of June 2025, the Favorite Poem Project will reside there, where it will continue to be overseen by Annette Frost (GRS’17), the project’s current director and another former student of Pinsky’s. And the archive continues to grow. Two of the most recent videos include BU President Melissa Gilliam reading “Caged Bird” by Maya Angelou and Provost Gloria Waters reading “If” by Rudyard Kipling.

Pinsky’s wish is that the project continues to flourish. “I hope that every regional accent, every part of the country, is represented in the Favorite Poem Project,” he says. “We need to make Favorite Poem videos in Texas, in Missouri, in North and South Dakota, in Ohio, in Arizona, etc. That is my very ambitious, sincere hope.”

Looking back and looking ahead

Now, as he prepares to teach his last semester’s last seminar, Pinsky is allowing himself a moment to look back on what he’s accomplished at BU. He says he’s proud of the fact that the number of applications to the MFA program continues to climb, due largely, he says, to the excellence of the instruction provided by former colleagues like Glück and the late Nobel laureate Derek Walcott (Hon.’93) and current colleagues like Karl Kirchwey and Ha Jin (GRS’94). And he points proudly to the relationship he helped launch between BU’s Creative Writing Program and Boston Arts Academy, a public high school in the Fenway. Each semester, BU sends a poet and fiction writer from the MFA program to the academy to help teach writing to the high schoolers.

“It is all that an outreach program should be,” Pinsky says. “For our students, it confirms the significance of what they’re doing here. For the Boston Arts Academy students, I hope the presence of our students is inspiring and confirming in another way.”

Then he adds, “I think every creative writing program in the country ought to emulate us and find a public high school to adopt.”

And then there are his nearly dozen collections of poetry—what he calls his proudest achievement, alongside his family. Next April, Princeton University Press will reissue his first collection, Sadness and Happiness, and his 1979 collection, An Explanation of America, in one volume. After he finishes teaching this spring, he’ll turn his attention to writing the preface for that book. And he promises he’s not done yet: “I have to keep writing poems.”

And he looks forward to spending more time with his wife of 64 years, Ellen, his three daughters, all of them “extremely distinguished in their fields,” he notes proudly, and his eight grandchildren.

As he prepares to bid the classroom goodbye, Pinsky says he’s bullish about the future of poetry.

“Poetry is fundamental. It’s like cuisine compared to nutrition, or lovemaking compared to procreation. It’s a basic human appetite. It’s a fundamental need.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.