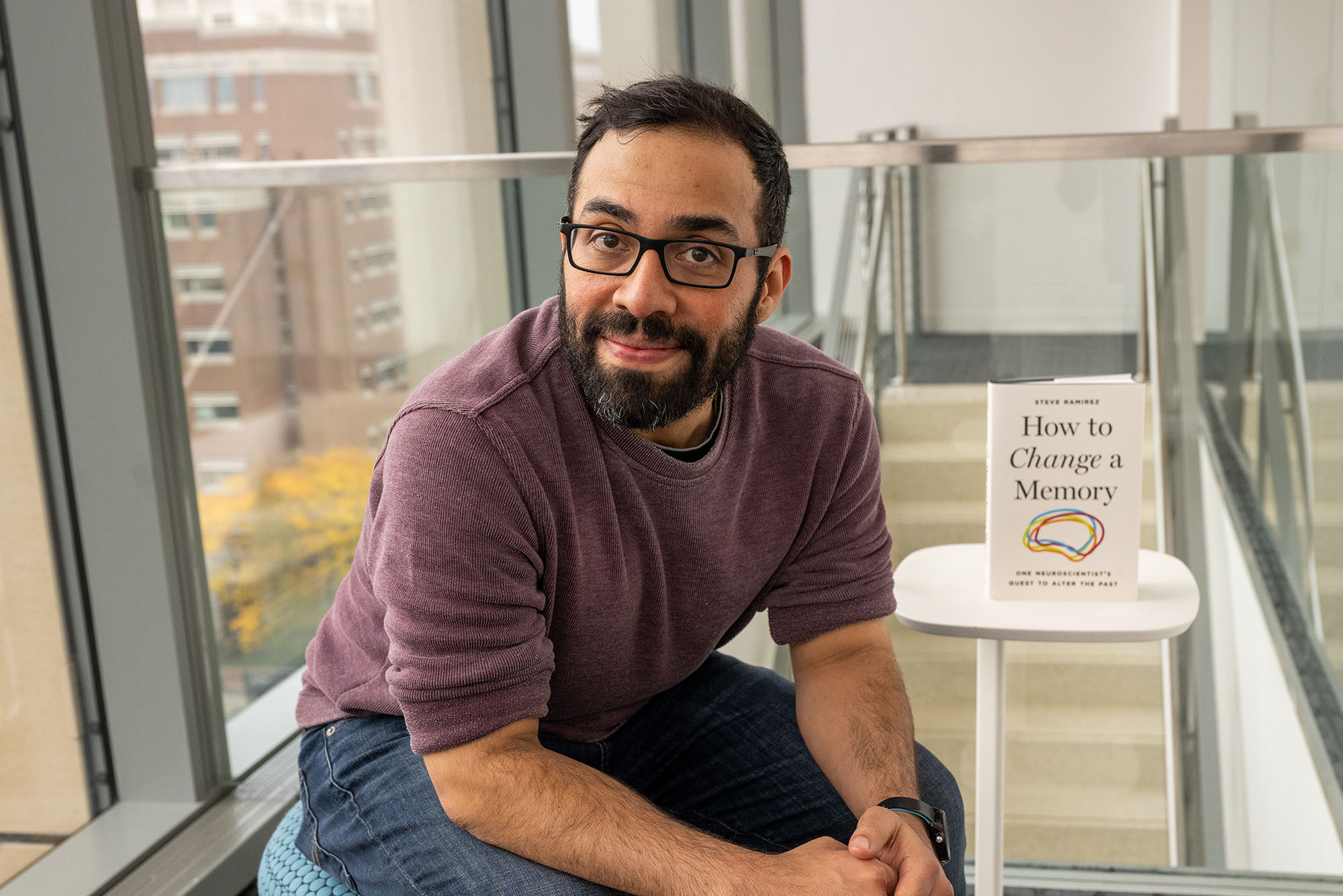

BU Neuroscientist’s “Riveting Debut” Book Discusses “How to Change a Memory”

Neuroscientist Steve Ramirez’s debut book plumbs memory’s malleability and manipulability, and key memories of joy and sorrow from his own life.

BU Neuroscientist’s “Riveting Debut” Book Discusses “How to Change a Memory”

Steve Ramirez draws on research and his own life for insights into the science of remembering, including creating false memories

Neuroscientist Steve Ramirez stuffs his Boston University office with memories: an inflatable T. rex gifted on his first day of grad school; an illustrator-autographed Spider-Man comic from his childhood; and lyrics to the 1990s rock song “All Star,” written on Post-it notes splayed across his wall, from one of his students a few years back. “I live more in my memory than most of my friends,” says Ramirez (CAS’10), a BU College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of psychological and brain sciences. “I really like going through memory lane.”

It’s an apt pastime for a scientist who describes memory science and how it manifests in our daily lives—including his own—in his first book, How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past (Princeton University Press, 2025). Ramirez is pioneering research on science’s emerging ability to manipulate memory, with the goal of improving mental health treatment. The book, which Publishers Weekly declared “a riveting debut,” is part memoir, part field guide, blending lay-friendly explanations of concepts like engrams—the physical traces that memories etch onto our brains—with autobiographical vignettes.

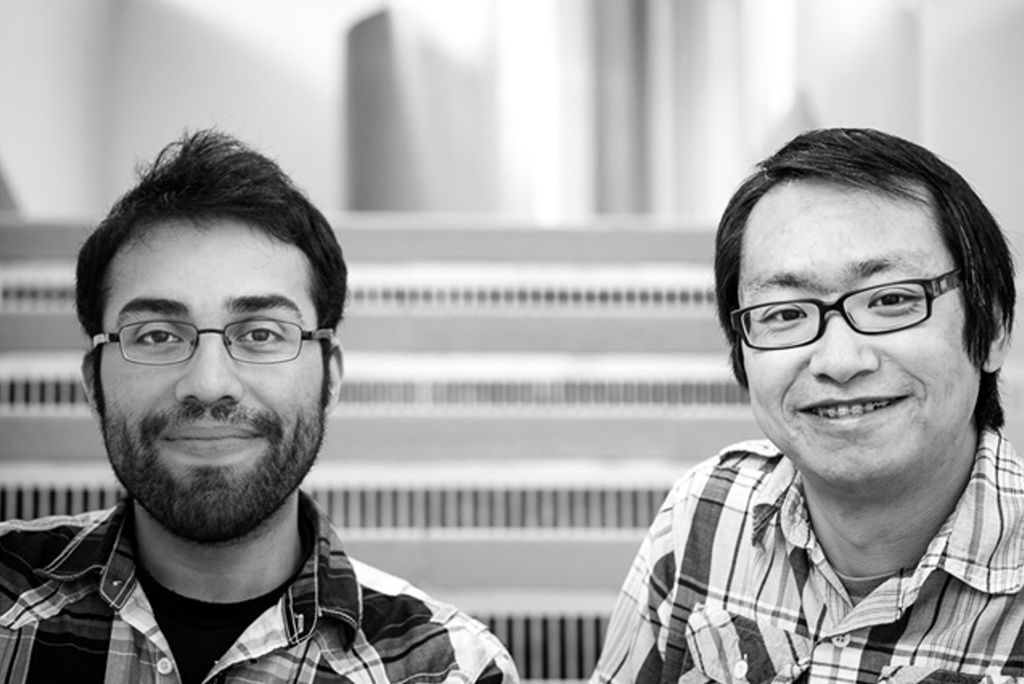

Prominent among those personal stories are scenes of Ramirez’s deep friendship with—and grief at the premature death of—his research collaborator and Northwestern University professor, Xu Liu, to whom he dedicates the book.

At BU, Ramirez is contributing to making science out of what once was science fiction. His research has included using mice to map the hippocampus, the brain’s warehouse for the building blocks of memory. When he was a graduate student at MIT working with Briana Chen (now at Columbia University), for instance, their team used a protein that lights up activated cells to reveal hippocampus cells that were turned on when the rodents formed memories from positive, neutral, and negative experiences. Subsequently, the duo targeted laser light on the cells to trigger those memories in the mice and alleviate depression-linked behaviors.

How to Change a Memory discusses this and other cutting-edge research that, Ramirez says, shows how “malleable and Silly Putty–esque our memories are. They’re not really like an iPhone video of the past. Every time we recall a memory, we’re constantly hitting ‘save as’ on a Microsoft Word file and updating it with some new information that we’re experiencing.”

The Pros and Cons of Memory Manipulation

Ramirez cites the conclusion of another neuroscientist who said that “the act of recalling a memory tarnishes it a bit.”

That’s a good thing, he says: “Being able to update memories means that we’re not literally stuck in the past” and can incorporate new information to make appropriate adjustments in our beliefs. This doesn’t mean that our remembrances are lies, he says, but rather that they “exist with a grain of salt in the brain.”

Being able to update memories means that we’re not literally stuck in the past.

What surprises Ramirez himself as a scientist is the effortless change in mood that memories can produce. As a born Bostonian and sports fan, if he recalls one of the Patriots’ Super Bowl wins, “I can get elated, euphoric.” Alternatively, if we sit with sad or difficult memories, “it can move you to tears in probably 10 seconds or less.”

The dual dynamic suggests the pros and cons of memory manipulation. His book notes the prospect of leavening clinical depression by medically triggering happy memories. On the flip side, it’s possible to sire false memories about things that never happened. Authority figures insisting on an untruth about an incident, for example, increases the likelihood that some people will remember it happening that way.

Does this mean everything relying on our memory is untrustworthy—from our ability to testify accurately in court to fighting fairly with our friends and partners, based on accurate recall of what we did or said? Ramirez notes that courts are increasingly integrating guardrails against flawed memory into their processes. And, he says, “most of our memory is still remarkably good.”

The People—and Memories—Behind the Science

Squeezing science and autobiography between two covers was, for Ramirez, the hardest part of realizing his lifelong ambition of writing a book. Browsing bookstores as a kid, he thought being on a shelf meant you had done work that mattered to humanity, as with Stephen Hawkings’ A Brief History of Time. The idea that personal matters might also be worthy of print clicked for Ramirez with Liu’s passing.

“All of the work that we’ve done in research—it was people doing the science, and the people have a very human element behind their story,” Ramirez says. “It’s really awesome seeing rockets landing back on Earth, or a breakthrough treatment, but I think that the humanity that leads to those moments of triumph is a heck of a story.”

His friendship with Liu threads throughout the book. The introduction opens with an example of memory’s amorphousness: Ramirez writes that he doesn’t recall most details about May 26, 2011, but he does remember working with a mouse that he and Liu used at their MIT research lab as PhD students, resurrecting a memory by targeting a painless laser at its brain. Ramirez treats readers to a less technical memory following publication of their findings, when he and Liu enjoyed a celebratory dinner atop Boston’s Prudential Center.

“I’ve never been so happy and so fully alive,” he writes, remembering the night. “I knew I’d repeatedly come back to this moment in my mind. The music and Xu’s voice were becoming part of my life’s soundtrack.” He bet his friend that if they ordered dessert, the waiter would recommend cookies and milk. (Ramirez won the bet.)

Ramirez admits he struggled in the years after Liu’s death. He writes of an alcohol addiction, partly from mourning his late friend, that had him falling down in public and nearly choking in bed on his own vomit. In the end, thinking about how memories are held and processed helped him on the path to sobriety: “think about what you’ll want to be remembering while on your deathbed, and do more of that in life.”

Years later, again in the Pru, Ramirez writes of what his recollecting that celebratory night in 2011 triggered: “Sometimes I’d recall this memory with Xu and feel empowered to continue doing science. Other times, this same memory led me to imagine all that could never be with Xu. I’d feel overwhelming sadness because it was a moment I could never recreate with him.

“And I would order dessert again to see him laugh out of pure joy; retrieving this memory was a miniature miracle in its ability to bring the past back to life.”