John Wilson’s Art of Black Humanity

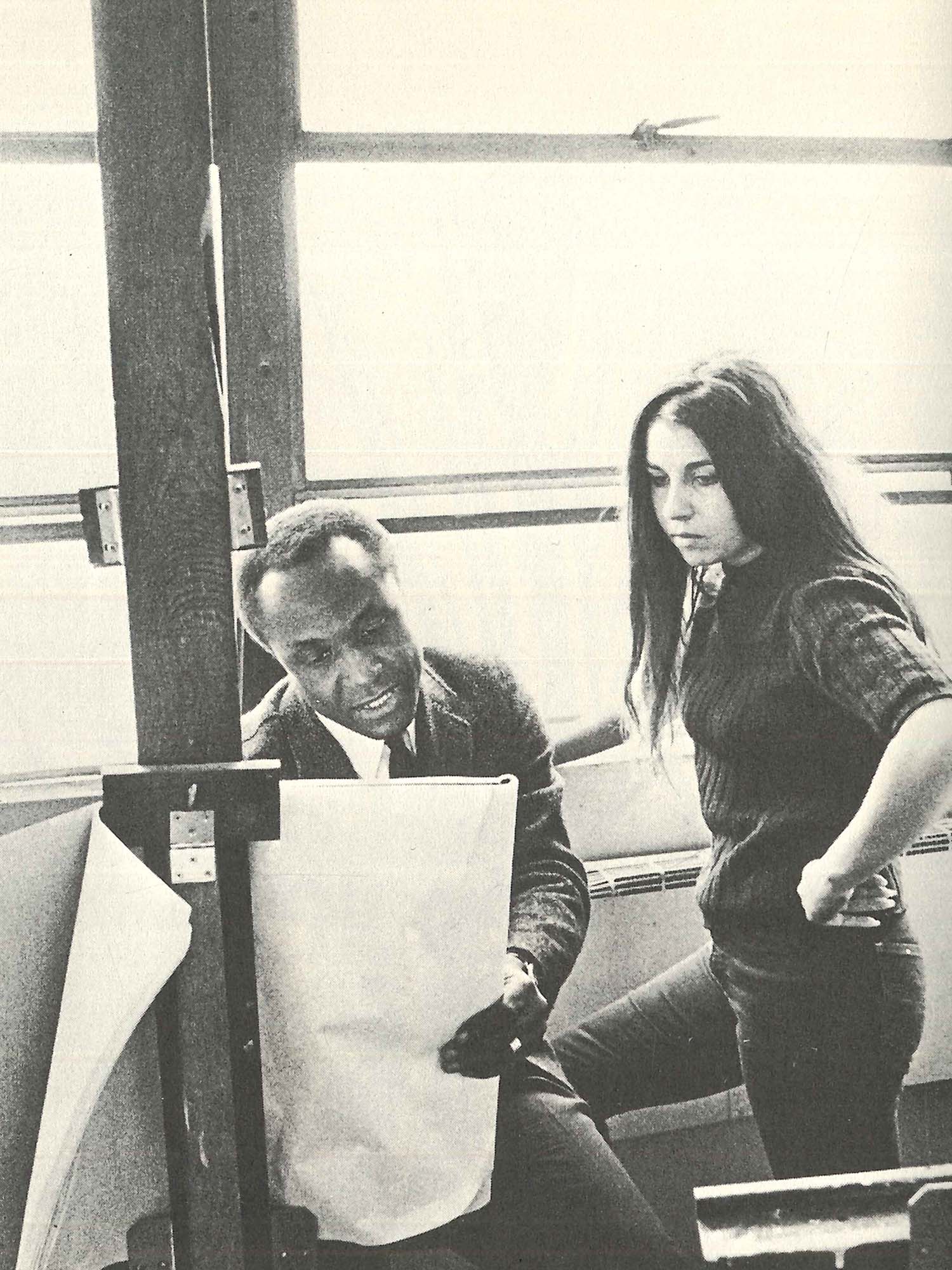

John Wilson with an unidentified student in a BU art studio, circa 1966. Wilson was a College of Fine Arts professor from 1964 to 1986. Photo by Don Brewster, from The Hub, Boston University College of Liberal Arts, 1966. From the University Archives Collection, Boston University Libraries, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

John Wilson’s Art of Black Humanity

MFA offers career retrospective of the late BU professor, complete with a comic by CFA students

The soul of John Wilson’s work is an insistence that Black people be fully seen in all their humanity.

Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson, the largest-ever exhibition of work by the late painter, sculptor, and Boston University professor has just opened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and will be on view through June 22.

“Wilson spoke very early on as a student of how the Black community was effectively invisible” in art and in the art world, says Edward Saywell, the MFA’s chair of prints and drawings, one of the exhibition’s four cocurators. “How he did not see images of the Black community that had dignity, gravitas, presence, and agency, and how so many of the images instead were ones that were caricatured, dehumanized.

“One of the constants throughout his work is the empathy and humanity that you feel,” Saywell says. “It’s one thing to be able to create a portrait that is sort of like a mimetic representation of somebody. It’s quite another to go beyond that, to really capture the soul, the spirit, the humanity, of the individual.”

Witnessing Humanity will move to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in September. Accompanying its run at the MFA are two projects by groups of students from the College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts, where Wilson taught for more than 20 years.

Co-organized by the MFA and the Met, the exhibition in the MFA’s Lois B. and Michael K. Torf Gallery comprises about 110 works, including drawings, prints, paintings, sculptures, and illustrated books, most pointing to Wilson’s continued artistic exploration of Black lives.

At its center is a scaled-down bronze maquette (or model) for his monumental sculpture Eternal Presence, a revered landmark, installed in 1987, on the grounds of the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA) in Roxbury, Mass., where Wilson grew up. Known as the Big Head to local residents, the piece radiates dignity and beauty. Though the maquette is located near the end of Witnessing Humanity, a large cutout in a wall frames the piece for visitors as soon as they enter the exhibition.

“You actually see through to the very last gallery, which allows you to connect across 50 or 60 years of work to the model for Eternal Presence,” says Saywell. “Wilson actually talked about how that sculpture answered the absences that he felt and saw that drove his work.”

Wilson (1922-2015) never quite got the level of acclaim he deserved when he was alive, because of a number of factors, and the exhibition is in part an attempt to redress that.

“It’s important to give people like that flowers when they’re still around,” says Joel Christian Gill (CFA’04), a CFA associate professor and chair of the School of Visual Arts MFA in visual narrative. “But, you know, better late than never.”

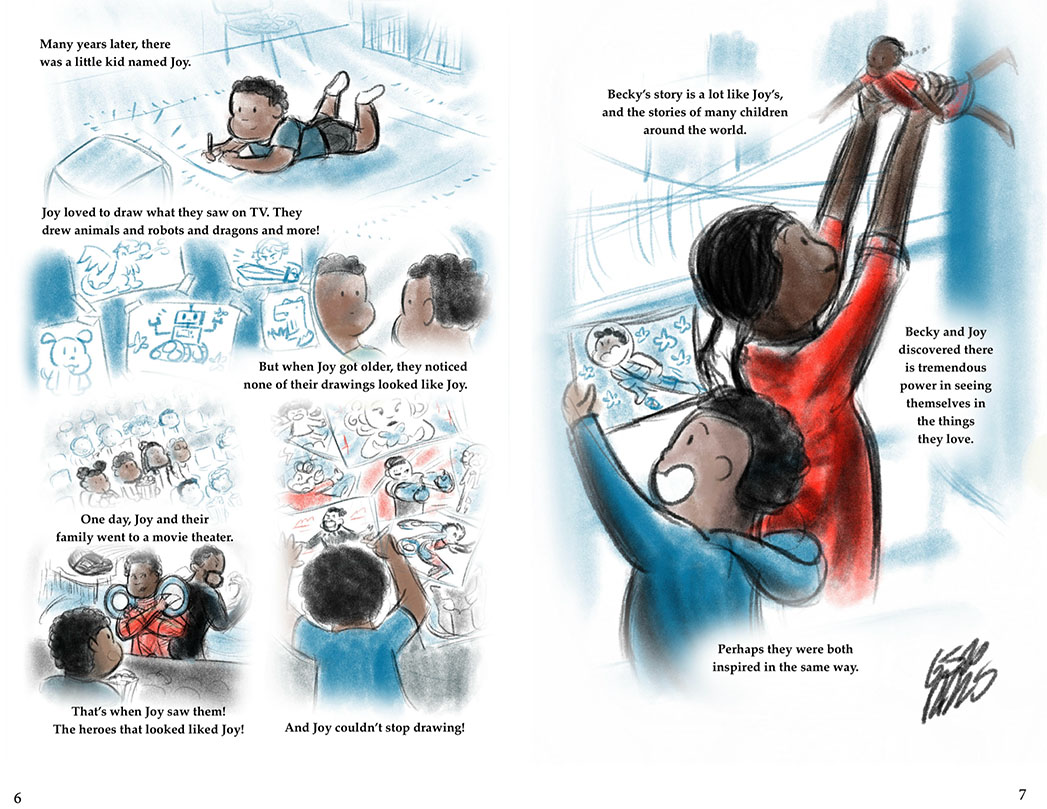

A dozen of Gill’s visual narrative students produced In Dialogue with Wilson: Comics Reflections on a Boston Visionary, a comic book in which each responds artistically to Wilson’s work. Created to be handed out at the exhibition, the comic is already in its third printing.

Students in first-year drawing classes at the School of Visual Arts—classes Wilson taught when he was on the faculty (1964 to 1986)—have also been invited by the museum to encounter the works and are producing their own in response, which will be on display in the Commonwealth Gallery at CFA March 17 through April 18.

“What we found very exciting about this is that the MFA reached out to us to really make this opportunity happen,” says Marc Schepens, director of the School of Visual Arts and a CFA senior lecturer in art, painting. “Historically, we’ve always worked quite closely with the MFA on basic things, these partnerships that have always existed. But on this we really started, as a school and a college, to connect with the museum on a higher level.”

The challenging gaze

Wilson’s vision may be most intimately displayed in the oil Self Portrait (1943), where the artist, wearing a red vest, looks directly into the eyes of the viewer.

“The gaze becomes inescapable,” Saywell says. “And this was made when he was 21, as a student, and it’s a work that has the gravity, the dignity of historical portraiture. It’s a challenging gaze, almost accusatory. There’s a stoicism, a strength, that’s in direct juxtaposition to what he described as the caricatures that he would so often see.”

In other works through the 1940s and ’50s, Wilson confronts racism directly, in searing images like 1952’s The Incident, about a Klan lynching. There was a period of populist images influenced by the Mexican muralists, created when he and his wife, Julie, spent time in that country in the 1950s. Julie was white, so they had to travel there in separate cars because of miscegenation laws in some states on their route.

A different tone gradually emerges in work from his years at BU. The Wilsons were longtime Brookline residents who raised two daughters and a son. Witnessing Humanity includes five panels from a 1970s series Wilson called Young Americans, depicting his son Roy and friends who passed through their home.

The exhibition also includes a “chill-out area,” with comfy seating and reproductions of many of the children’s books Wilson illustrated for visitors to peruse.

The MFA and the Met were among museums that began acquiring Wilson’s work when he was still a student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (he graduated in 1944) or soon after. But he never got the renown that start suggested—for many reasons, Saywell and Schepens say. Overt and subtle racism, of course, but also Wilson’s decision to remain in Boston when the center of the art world was in New York. Opting for figurative painting when abstraction was hot was another. And he was not as prolific as some artists, in part because he worked as a teacher and an illustrator.

But there’s no doubting his impact on the Black community of Roxbury and Mattapan.

“We all know what the Big Head is. That is our landmark. That signifies our safety, it signifies our childhood. We grew up playing on that statue,” local resident Diamond (D.) McMillion-Williams says in a video about Eternal Presence that runs on a loop in the exhibition.

We all know what the Big Head is. That is our landmark. That signifies our safety, it signifies our childhood. We grew up playing on that statue.

“It is one of the first pieces of art that I’ve ever seen that looked like me, where my features were magnified, where my features were made to be beautiful,” they say. “A lot of the ‘art’ in our community is statues of people who kept us down, for a lack of a better way of saying it. We don’t see things that resonate with our power, with our beauty. Right?”

With Wilson’s sculpture, “we had something in our community that showed us that we were beautiful. I can’t necessarily say that about any other piece of art in the city of Boston,” McMillion-Williams says. “The Big Head is ours.”

Comic art and identity

“The very act of being an artist who makes work that celebrates the lives of Black and brown people, no matter what the context is, is a political act,” Gill says. “Making this work and celebrating it, especially in the times that we are living in, is an important thing.”

The MFA invited the two groups of BU students to the museum last fall to encounter Wilson’s work close-up in a study room, before the exhibition was hung.

“The way that Wilson’s work speaks to issues of identity is incredibly important,” Schepens says. “In the contemporary context of the art world, we see a lot of artists who use figuration as a way to give representation to people of different backgrounds and identities who have not necessarily seen images of themselves in museums and galleries before.

“But I think one of the interesting things and important things that we see is Wilson engaging in this conversation going back to the late 1940s,” he notes.

The students’ comic, or zine, as Saywell calls it, features everything from a student reacting to Wilson’s Down by the Riverside, a set of prints inspired by a Richard Wright work, to another meditating on the need to draw people, not just line and proportion.

“A lot of us felt very proud and honored to be able to react to such beautiful work,” says Emma Varteresian (CFA’26), a visual narrative student who designed the comic. She graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 2024, but didn’t know Wilson’s name before she began work on the project, although she had seen the Big Head when she lived in Roxbury. “Why didn’t I hear about him before, if he was such a big part of both of these institutions that I’ve been in for all these years? So it feels like a long time coming, to finally show how beautiful [his work] is.”

The MFA printed 150 copies of the comic to give away at the exhibition, which opened February 8; a second printing ran out less than two weeks after the opening. A third printing of 1,200 copies is underway. And there’s the possibility the comic will also be available when the show moves to the Met in New York.

“I couldn’t be more proud of the work they did,” Gill says. “I say this so many times that at some point somebody’s going to tell me to stop, but when we dig up an ancient civilization, we don’t dig up their politics. We don’t dig up their accountants. We don’t dig up their engineers. We dig up their art. And that’s the way we see a world, through their art.

“What would happen if, you know, like 500 years from now, America is a memory and we dig up the art?” Gill asks. “What does our art say about us? It says that we’re complicated. And work like John Wilson’s says, ‘You can see how beautiful I am and should be ashamed for ignoring me for as long as you have.’”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.