Is There Life on Other Planets? BU Astronomer Helping Lead New Mission Seeking Hints of Life in Space

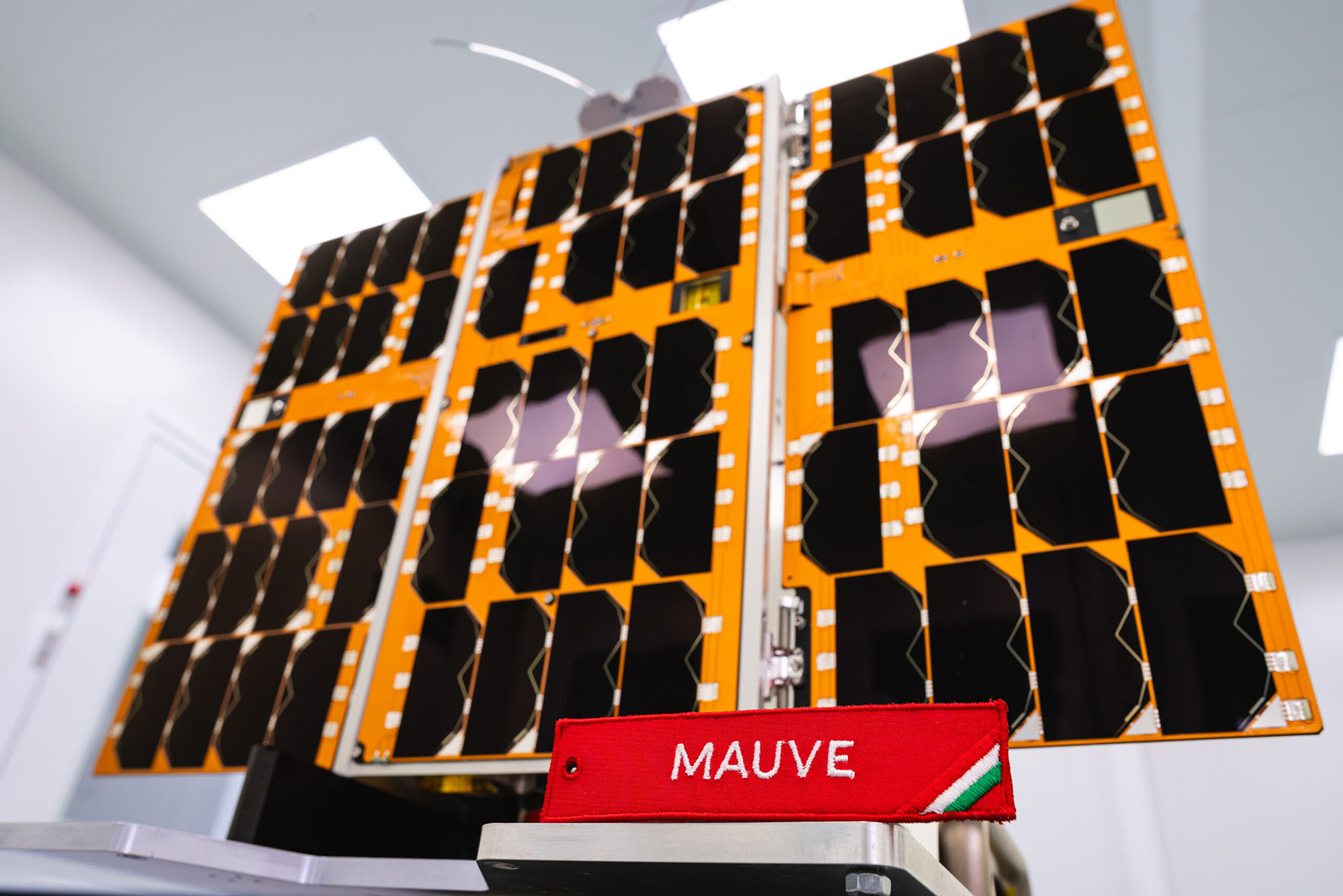

Blue Skies Space launched Mauve on November 28 from Vandenberg Space Force Base. Photo via SpaceX/Blue Skies Space

Is There Life on Other Planets? BU Astronomer Helping Lead New Mission Seeking Hints of Life in Space

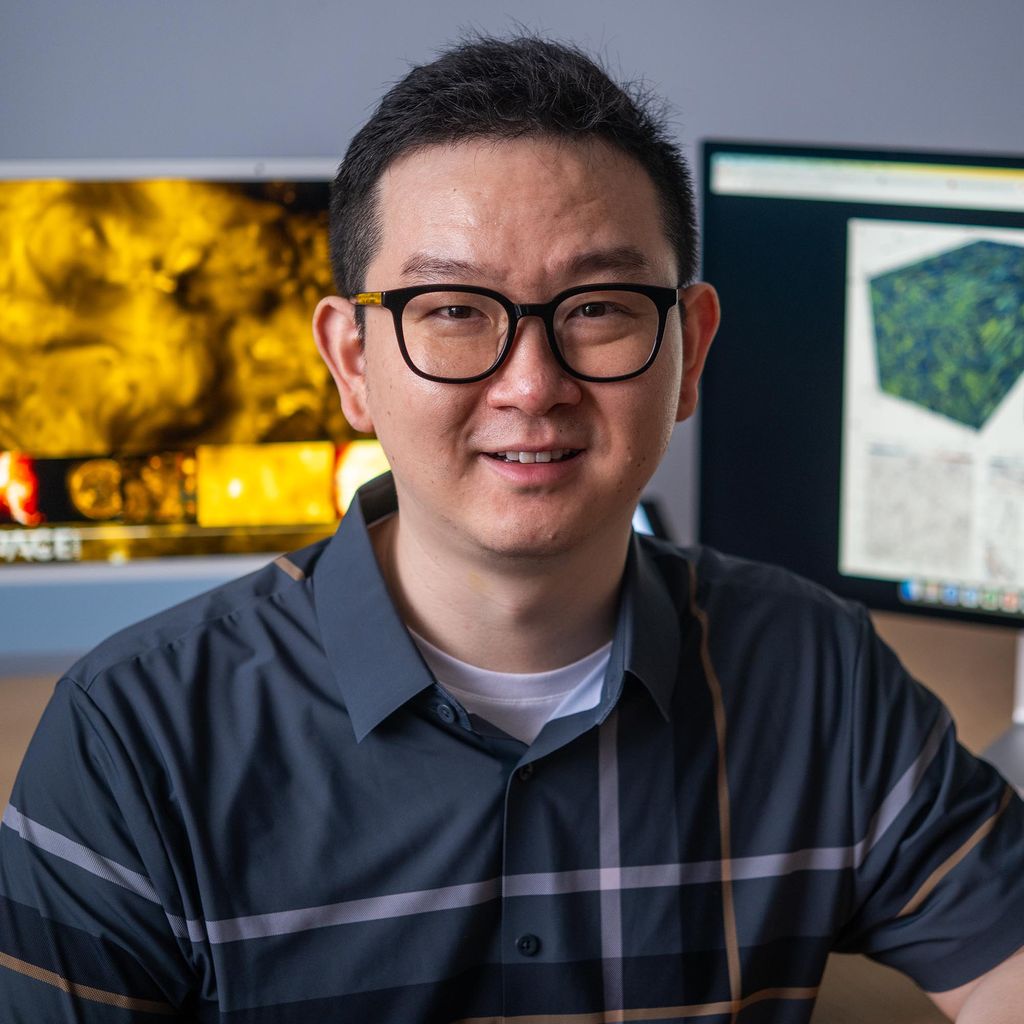

Chuanfei Dong, a CAS assistant professor, is helping lead Mauve satellite’s study of stars’ bursts of plasma and magnetic fields

Boston University astronomer Chuanfei Dong researches a question that’s been asked since antiquity: Could life exist on worlds beyond Earth? Now, he’s helping lead the research arm of a new, private space mission that will look for an answer.

Blue Skies Space launched Mauve, a satellite smaller than a microwave oven and outfitted with a telescope, on November 28 from Vandenberg Space Force Base in Southern California. Dong, a BU College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of astronomy, is a principal investigator on Mauve, which will peer at stellar activity—phenomena occurring on the surfaces of stars—in our Milky Way galaxy.

He researches the physics of plasma—superheated, ionized gases comprising over 99 percent of the visible universe, including Earth’s sun and other stars. The Brink asked Dong what he hopes to learn and how Mauve, carried aloft by a SpaceX rocket, ties in with his broader research.

Q&A

With Chuanfei Dong

The Brink: Could you describe the mission of Mauve? What do you hope to learn from the mission regarding planetary habitability?

Dong: In simple terms, Mauve is a space telescope designed to study stars in our galaxy in ultraviolet (UV) light. One of the main goals is to understand how stars behave—especially how their magnetic activity, flares, and high-energy radiation influence the planets that orbit them. This is key to understanding whether planets around these stars might be habitable. Since most stars likely have planets, learning how stellar activity affects potential habitability helps us answer the big question: Could life exist elsewhere?

The Brink: How will Mauve fulfill that mission—what instruments will it use and how do they work?

Dong: Mauve will detect and study energetic eruptions on stars, known as coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, which are massive bursts of plasma and magnetic fields. On the sun, CMEs can be seen directly with space telescopes, but for other stars, we can’t get such clear images. Instead, Mauve will use a clever, indirect method: it will look for subtle dimmings in the star’s light that happen after flares, similar to how solar material temporarily blocks some light on the sun. These dimmings serve as fingerprints of CMEs.

To do this, Mauve’s instruments will focus on key spectral lines that are very sensitive to changes in the star’s atmosphere and any material erupting from it. By watching how the brightness in these lines decreases after flares, Mauve can detect CMEs even from stars many light-years away.

By observing many active stars over long periods, Mauve will collect a statistical picture of how often these eruptions happen, how strong they are, and how long they last. This information is critical for understanding how stellar activity affects the environments of nearby planets and whether they might be habitable.

The Brink: How long will the mission last?

The mission is planned as a three-year survey.

The Brink: Why are existing telescopes—on Earth and in space—unable to detect what Mauve will see?

Earth-based telescopes cannot see UV light because our atmosphere blocks it. Even space telescopes like Hubble aren’t dedicated to continuous UV monitoring of stellar activity. Mauve fills this gap.

The Brink: Could you describe your broader research interests, and how Mauve fits in with them and will advance them? How did you get interested in these questions?

I study the interaction between stars and planets, particularly how stellar magnetic activity affects planetary environments and habitability. Mauve aligns perfectly with this work, because it gives us the detailed UV data needed to quantify these effects. My interest stems from the fundamental question of whether Earth is unique and how we might find habitable worlds elsewhere. By understanding active stars and their impacts, Mauve directly advances our ability to assess which exoplanets could support life.

Mauve is a collaborative mission: its survey program is open to scientists worldwide, including PhD students and early-career researchers. We hope it will provide a wealth of data that inspires discoveries not only about stars, but also about the potential for life beyond our solar system.

Funding for Mauve came from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research program and the United Kingdom Research and Innovation’s Horizon Europe guarantee scheme.