Through Instagram, BU Deaf Studies Empowers the Deaf Community

Accounts focus on research, student life, and public outreach; “All of the posts have impacted someone who is in need.”

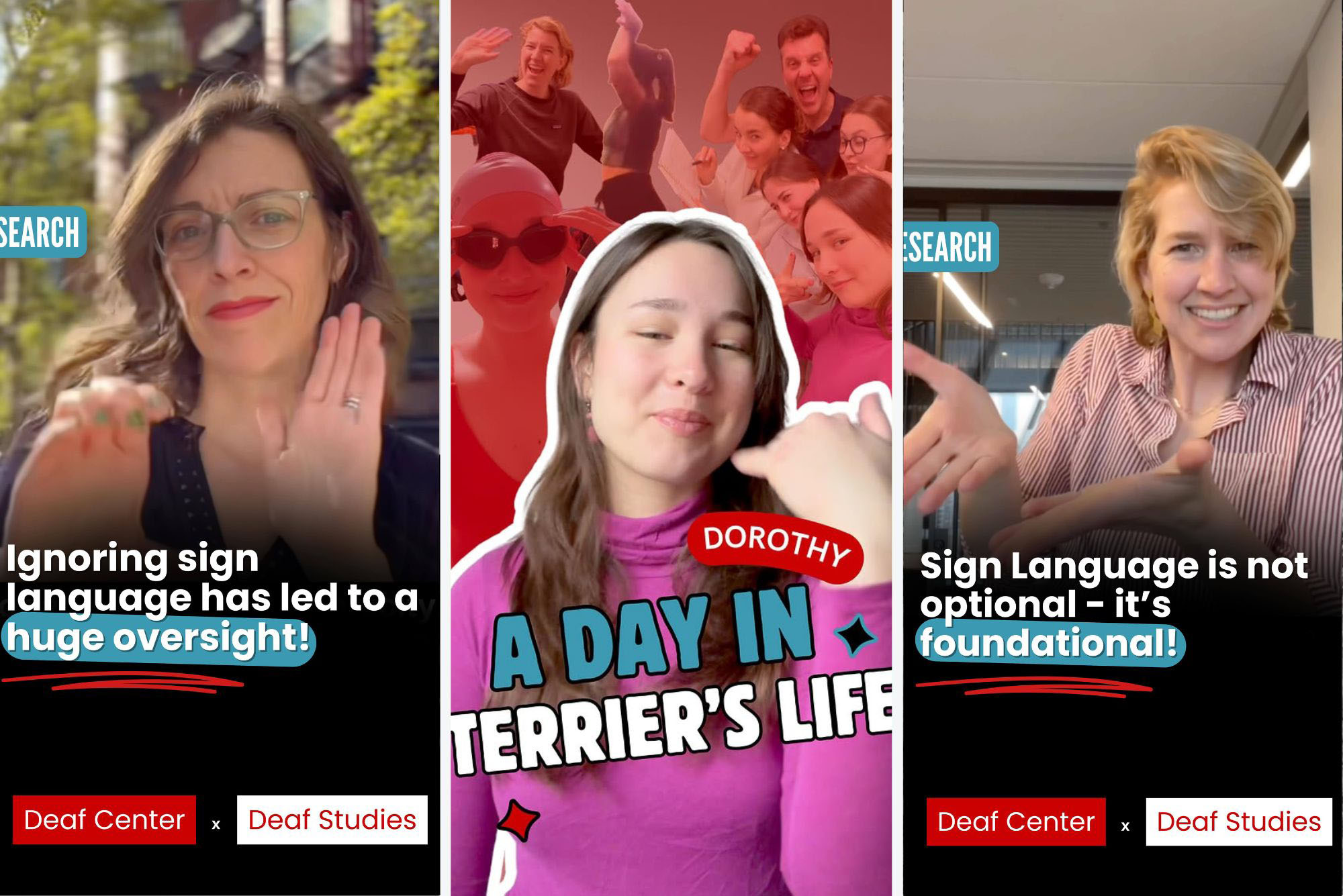

Screengrabs of some of the accounts’ most popular posts. Photos courtesy of BU Deaf Studies

Through Instagram, BU Deaf Studies Empowers the Deaf Community

Accounts focus on research, student life, and public outreach; “All of the posts have impacted someone who is in need.”

There’s one post on Instagram explaining financial literacy research that helps deaf students build money skills. There’s a story of a Boston University professor who learned American Sign Language (ASL) so she could communicate with her five-year-old deaf son. There’s a post of BU President Melissa Gilliam receiving her “Sign Name”—an honor where a person is given a unique name through sign language and welcomed into the deaf community.

These social media posts are just some examples of the growing digital movement led by the BU Deaf Center and Deaf Studies program at BU Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. Through the team’s two Instagram accounts—BUDeafCenter and BUDeafStudies—they are reframing how academic research can reach, represent, and most important, empower deaf and hard-of-hearing children as well as those who care for them.

According to the 2023 American Community Survey, approximately 2 percent of the US population identifies as deaf or hard-of-hearing, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders has found that over 15 percent of adults report having some difficulty hearing. Then there is this striking statistic: while 90 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, very few of those parents learn ASL.

The BU team’s efforts are working, and getting noticed far beyond BU: since its launch in January 2024, the BUDeafCenter Instagram account has grown from 1,700 to over 6,600 followers, with a total reach on Facebook and Instagram surpassing two million by December 2024. All of their posts are in both ASL and English, and have both transcriptions and video descriptions.

“Social media is a powerful way to share knowledge and deliver this information,” says team communications specialist Britta Schwall (Wheelock’25), who is deaf. “We wanted to make sure that the content was getting out there in an accessible way and to foster a sense of community, too.”

Impacting the deaf community beyond BU

One of the team’s most effective posts to date features Andrew Bottoms, a Wheelock senior lecturer in deaf studies and director of the Deaf Studies program. In a video on Instagram, Bottoms addresses a widespread, but often overlooked issue: deaf kids are often touched and physically manipulated to look in a certain direction, sometimes in inappropriate or violent ways.

“Research shows deaf kids are experts at absorbing and managing their visual attention,” Bottoms signs while looking at the camera. “Hearing kids use both hearing and sight to understand the world, while deaf kids use their eyes to absorb everything around them. They each do it their own way… It’s better to let them guide their focus—they know what they need to see.”

In this Instagram video, Andrew Bottoms, a Wheelock senior lecturer in deaf studies and director of the Deaf Studies program, explains how deaf kids are often touched and physically manipulated to look in a certain direction.

“We wanted to highlight that [deaf children] have visual needs, and also empower them to be independent and to understand and take in the world themselves, without having their bodies manipulated,” says Marshall Hurst (Wheelock’25), the team’s second communications specialist.

(BU Today spoke with both Hurst and Schwall through ASL interpreters.)

Prompted by conversations with Hurst and Schwall, Bottoms created an Instagram video explaining this phenomenon and offering alternative solutions. In the video, he stares straight into the camera, while signing alongside closed captioning.

“Research shows that these children are experts at using their eyes to take in everything around them, making them highly skilled at navigating their environment,” the post’s caption reads. “It’s essential for kids to learn how to direct their own attention and explore what interests them.”

The Instagram video is the team’s highest viewed reel, with over 88,000 views, 2,600 likes, and nearly 1,400 shares. It received 170 comments, with many asking to be sent the research study Bottoms cited in the video. “YES, aren’t visually-centered deaf children amazing? We can learn a few things from them, actually,” one commenter wrote.

In this Instagram video, Marshall Hurst highlights BU research about the benefits of exposing deaf babies of hearing parents to ASL.

Another post (starring Hurst) highlights BU research that found deaf children of hearing parents who were exposed to ASL in the first six months of their lives developed vocabularies just as strong as those with deaf parents who are fluent signers. It didn’t matter whether the hearing parents were fluent in ASL or not. This reel had nearly 50,000 views and 600 comments.

A follow-up post promotes a free webinar cohosted by BU and Gallaudet University—the world’s only college for people who are deaf or hard of hearing—on how hearing parents learn ASL to communicate with their deaf children.

“It’s such a common story, and yet it’s not a frequently told one,” Schwall says. “There’s such a need to change that. It’s really life-threatening, this kind of circumstance where a child is not getting their language access at an early age…that crucial window of language access and acquisition. Essentially our goal was to save deaf children from this experience.”

Naomi Caselli, a Wheelock associate professor of deaf education and director of the Deaf Center, says the team received advice early on from a deaf social media influencer on how to improve the account and foster more engagement. “Not self-serving kinds of posts—we got a grant, wrote a paper,” she says. “Instead, make it about ‘this grant that will change your life.’ Flip it, rather than brag about ourselves. Make that value clear. You have to treat social media like a genre.”

Beyond likes and shares

One strategic move the social media team made was to divide up their accounts. BUDeafCenter is focused on research, publications, and nationwide issues, as well as other activities involving life outside of BU. At the same time, BUDeafStudies focuses more on student life, recruitment, and current events on campus.

This post follows Dorothy Steinle (Wheelock’26), a graduate student and research assistant, through a typical day.

“The likes and views are nice, but not our entire focus,” Schwall says. “Our focus is to really get our research out there for everyone to be able to know and access it and know what we’re doing.”

“Really all of the posts have impacted someone who is in need of that information and maybe is experiencing frustration, not sure what to do, or is ill-equipped and [needs access] to the right tools,” Hurst says.

Caselli says the team was surprised when followers started commenting and asking how to access articles mentioned in their posts. Since specifically offering in their posts to send along the studies, hundreds of people, mostly non-academics, have asked for them to do so.

The team took inspiration from other inclusive creators and educators, including “Why I Sign,” “Rise and Sign,” and “That Deaf Family,” which follows two deaf parents who are raising one child who is deaf and another who is hard of hearing, and how they blend ASL and English in their home.

“We realized that we had a value to the deaf and hard-of-hearing community,” Hurst adds.

One family who has benefited so far is that of social media influencer Callie Foster, who learned that her son Luca was deaf at birth. In an interview with People magazine, Foster credited her education and awareness of deaf culture, as well as information on raising a deaf child, to multiple deaf social media creators, including the BU Deaf Center, which she follows on Instagram. “I have taught myself through various modules, free apps, and paid classes, and my husband and I are continuing to educate ourselves with ASL further,” Foster said.

The ongoing mission

Though Schwall and Hurst both graduated from BU this May, their mission to help the deaf community won’t end. Hurst is moving to Austin, Tex., to take a job as a high school English teacher at the Texas School for the Deaf, and Schwall will continue to work at the ASL Education Center in Northborough, Mass., helping with the center’s marketing and translation coordination. A new crop of Wheelock grad students will continue to build on the social media efforts here at BU, with the aim of growing the accounts and reaching even more.

Hurst says that running the accounts has demonstrated to them how social media can serve as a community space for the deaf community worldwide. “This is a way for the deaf community to share narratives by us, for us, within the community,” he says.

The team’s content also helps to “bust some of those myths, assumptions, stereotypes, and ignorance” the public has towards the deaf community, and it “really [tries] to focus on education,” Hurst says. “We want to have a safe place for the community to be able to share information and engage.”

Asked why the team is investing so much energy in this kind of communication, Caselli says it is important not just to share research in traditional academic venues, such as paywalled scholarly journals and conferences that are expensive and inaccessible to people outside academia. “Publicly funded work should be driven by, and accessible to, the taxpayers who support it, and these online platforms have given us an opportunity to share the research directly with the people who need it most: parents of deaf and hard-of-hearing kids, the educators and healthcare providers who support them, and deaf communities more broadly,” says Caselli, who is also director of the AI & Education Initiative. “While academics and researchers are one important audience, the research is meant to change people’s lives. So it’s important that we meet people where they are, and people are on social media. We had to figure out how to bring the research findings to social media, in ASL, in ways that are accessible.”

Former coworkers say that working on the deaf education and studies department’s Instagram account has helped them think about how solutions and strategies for the deaf community can ultimately benefit everyone.

Schwall highlights how inclusive practices, such as captioning, benefit not only the deaf community, but also the general public. “Its universal design benefits everybody in the community. Accessibility is inclusivity,” she says.

Hurst points to how the MBTA now uses a scrolling message board on its trains to announce which stop is coming up next, instead of just a verbal announcement as they used to do. “That’s a way for everybody—deaf and hearing people—to know what’s going on around them in a very noisy environment,” he says.

“Our social media efforts [aim] to make people more knowledgeable and to empower them to figure out how to navigate the world the right way with the right resources,” Schwall says. “And with new media and technology, things are always changing, right? There are all of these new tools we see every day—TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Chat GPT. We’re really just seeing all of this technology that helps us, and we can use it for a benefit to make the world a better and more accessible place.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.