Our Identities Are More Than Our Genes, Says BU Researcher in Debut Book

In Where Biology Ends and Bias Begins, Shoumita Dasgupta illustrates what we risk—and lose—when we attribute our differences only to biology

A quick distillation of a person down to their DNA misses so much of our human complexity, says BU biomedical geneticist Shoumita Dasgupta.

Our Identities Are More Than Our Genes, Says BU Researcher in Debut Book

In Where Biology Ends and Bias Begins, Shoumita Dasgupta illustrates what we risk—and lose—when we attribute our differences only to biology

It might be said of someone who is particularly resilient to illness that they’ve got “good genes.” The same is often said of people who are tall, or conventionally beautiful, or gifted athletes—or who possess any of the other qualities society prizes.

But this quick distillation of a person down to their DNA, even if it was well-intentioned or even simply offhanded, misses so much of our human complexity. And, in the worst cases, evoking genetics to define an individual risks hiding biased stereotypes under a sheen of scientific validation.

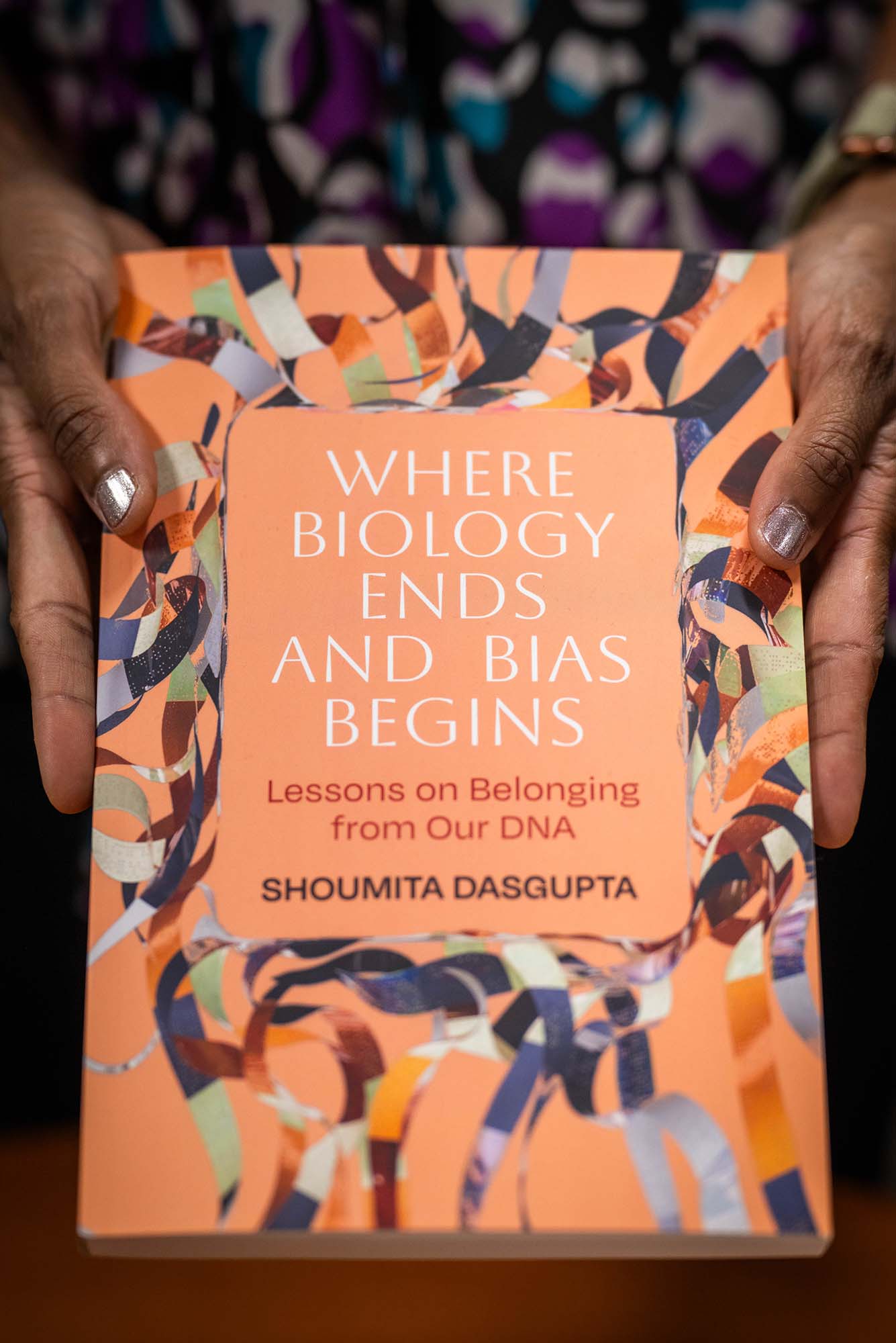

Those are the arguments central to Boston University professor Shoumita Dasgupta’s new book, Where Biology Ends and Bias Begins: Lessons on Belonging from Our DNA (University of California Press, 2025). The book, by an expert in genetics, draws on the latest science to correct common misconceptions about how much of our social identities are actually based in genetics.

The Brink spoke with Dasgupta, a BU Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine professor of medicine, assistant dean of diversity and inclusion, and founding director of the Graduate Program in Genetics and Genomics, about her book and the lessons it contains.

Q&A

with Shoumita Dasgupta

The Brink: What is “genetic essentialism” and why is it a misguided belief system?

Dasgupta: I think the best way to explain genetic essentialism is to refer to the wonderful analogy from Camara Jones that she refers to as “The Gardener’s Tale.” In this parable, she illustrates the concept using two sets of flower seeds: one planted in a pot with old, sandy, rocky soil, and another that she filled with fresh, nutrient-rich soil. The seeds had the same genetic potential, but the seeds planted in the old soil struggled to sprout, while the seeds planted in the fresh soil were off and running. As a gardener, it became natural to gravitate toward the flowers that were doing well, providing them the perfect water and sunlight and fertilizer, while the other flowers were steadily ignored.

This is a way for us to think about systemic or institutional bias; the gardener was favoring—consciously or not—one set of flowers over another and promoting their environmental advantage. At the end of the season, the flowers planted in the rich soil were thriving, while the ones planted in the poor soil were not.

A genetic essentialist would conclude that the robust flowers came from genetically superior seeds—that the differences we can see visually must reflect additional underlying genetic differences that impact growth. However, this essentialist thinking ignores the influence of the many structural and environmental factors that we know contributed to the disparate outcomes.

In the case of human traits, this means that people grouped by social categories might be viewed as genetically inferior or superior rather than as the product of the biased social forces that impact their health and well-being.

The Brink: You describe this book as something of a myth-busting endeavor. What myth(s) are you aiming to debunk?

Dasgupta: Myths about human difference really are tough to bust because of the combination of messaging from society and our own attempts at sensemaking from a young age. Media is constantly telling us that people from one part of the world are dangerous, or people of a particular gender are not smart enough to pursue intellectually demanding careers. These messages are hard not to internalize, even for members of the very groups that are being mischaracterized. And with respect to sensemaking, our brains are wired to come up with rules of thumb that can help us take mental shortcuts—but those shortcuts are often stereotypes. We have to fight these pervasive messages and instincts in order to bust these myths.

I would love for people to hold onto the concept that, when thinking about human difference, variation is continuous, there are no discrete categories, and there is nowhere on the planet that you can draw a clean line that separates one group from another. Our identities are intersectional, which means we are all unique, in a beautiful and messy way.

The Brink: Biology is often invoked to defend perceived differences—in terms of race, gender, and more. Your book shows that our biology is complex and often not as cut-and-dried as it seems. What can an appreciation of that complexity teach us about ourselves and each other?

When people use genetics to “prove” group membership, they are missing the larger point that most human genetic variation is within groups, not between groups, so there is no one uniform signature that corresponds to all members of a single group. Rather, our DNA demonstrates belonging to a larger group—that of all humans.

The Brink: We live in a time of unprecedented access to our own genetic information, and, for pregnant people, the genetic information of their embryo. This comes with some challenges, as you outline in the book. Is there any benefit to this wealth of genome-level information? What potential does this field hold?

It is truly amazing the ways in which our understanding of genetic science has advanced just in the short time of my career.

When I was a new faculty member, in 2003, the human genome draft sequence was just being released. And now, in 2025, we have incredible tools to predict people’s risk profiles for genetic conditions, and, increasingly, we have the ability to even supply new copies of genes or edit copies of genes that need to be tweaked to restore function. This trajectory of technology development is truly astounding and is something to be celebrated.

The flip side of rapid technology development, though, is that sometimes the full ramifications of the technology are not evaluated on the same accelerated time frame. That is why it was prescient of the National Human Genome Research Institute—one of the institutes of the NIH [National Institutes of Health]—to establish a new branch of research related to genomics focusing on ethical, legal, and social implications of the work.

This is truly a golden age for genomics; we just need to be vigilant that we don’t leave anyone behind and amplify injustices in this era of genomic innovation.