Best of The Brink 2024: 10 Inspiring Inventions and Discoveries—All from BU Researchers

Highlights from a year of BU research, from an AI program that can predict Alzheimer’s disease to an ancient Egyptian treasure

Just some of the discoveries and breakthroughs fostered by BU researchers (clockwise from top left): a skin cancer detection device, a record-breaking robot, a slice of ancient Egyptian history, and deep-sea rocks that generate oxygen. DermaSensor/Business Wire, Jackie Ricciardi, Cydney Scott, and Wikimedia Commons/Geomar Bilddatenbank/ROV KIEL 6000, GEOMAR

Best of The Brink 2024: 10 Inspiring Inventions and Discoveries—All from BU Researchers

Highlights from a year of BU research, from an AI program that can predict Alzheimer’s disease to an ancient Egyptian treasure

They’re the kind of discoveries and inventions that could change and even save lives. And they all got their start in Boston University labs: a device that can spot skin cancer using light, an AI program that can predict Alzheimer’s disease, a more effective COVID vaccine. The Brink reported on each of these breakthroughs—and many others—in 2024.

And we shared some big surprises, too, like the 5,000-year-old Egyptian treasure found on campus, the giant space cloud that messed with Earth’s climate, and a record-breaking robot. With the year winding down, we wanted to bring you some of our favorite highlights from BU research.

But, before we jump in, we’d like to celebrate some other accolades: four of our stories won big awards. The nonprofit Council for Advancement and Support of Education gave The Brink Best of District I writing awards for its articles on Black women’s health, a diabetes treatment breakthrough, and two molecular biologists who fell in love with the same science—and each other. We also scooped a best video award for our moving story on Parkinson’s disease research volunteers.

1

A new noninvasive skin cancer detection device that uses technology pioneered at BU could reportedly cut the number of missed skin cancers by half. The DermaSensor directs pulses of light at tissue, tracking the colors that bounce back—malignant and benign lesions scatter light differently—to help clinicians decide whether to refer a patient to a specialist. Around one in five Americans will have skin cancer at some point in their lives, according to the American Academy of Dermatology. The sensing technology was developed and refined by BU engineer Irving J. Bigio. In January, the Food and Drug Administration cleared the DermaSensor for US markets; in October, Time named it one of its inventions of the year.

2

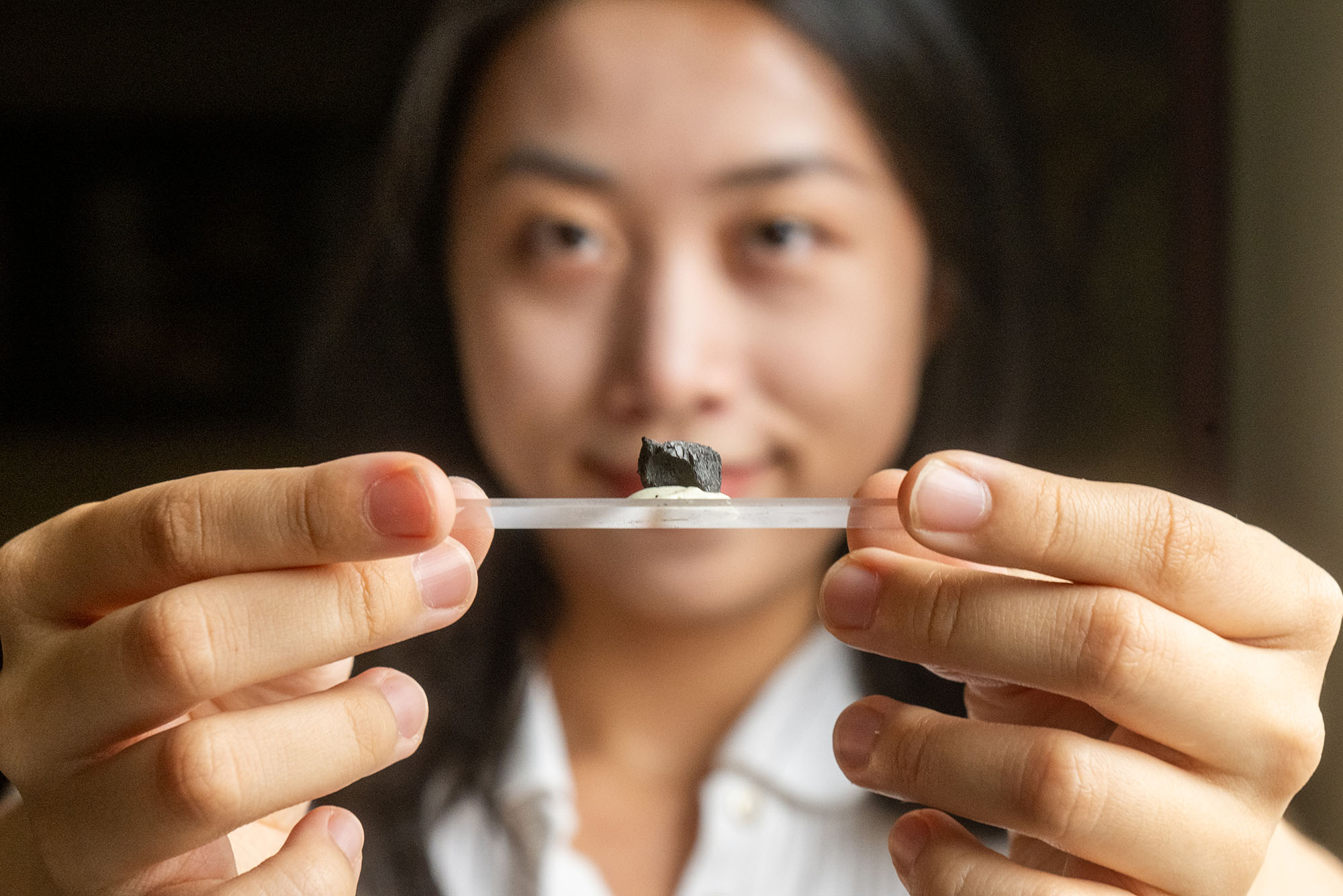

BU’s urban Charles River campus—with trolley trains rattling on one side, highway traffic rushing past on the other—is an unlikely place to find ancient Egyptian treasure. But when Egyptologist Kathryn Bard retired from the University in 2022, she gifted a colleague a long-forgotten cardboard box of samples collected in the 1980s from two predynastic Nile Valley settlements. Among them were chunks of 5,000-year-old wood charcoal. Not exactly a stockpile of gem-studded jewels, but a true treasure to student researcher Ranran (Angela) Zhang (CAS’24). Zhang studied the ancient charcoal to learn about early Egyptians’ interaction with their surrounding environment, like whether they made homes for the short or long term. “I like that you’re looking at common people and what these common people ate and used,” said Zhang. “And we’re able to reconstruct the daily activities of commoners like me.”

3

A multidisciplinary team of BU engineers, neurobiologists, and computer and data scientists created a machine learning model that can predict whether someone with mild cognitive impairment is likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. The artificial intelligence program, which analyzes speech, had an accuracy rate of 78.5 percent.

“We hope, as everyone does, that there will be more and more Alzheimer’s treatments made available,” said Ioannis (Yannis) Paschalidis, director of the BU Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering. “If you can predict what will happen, you have more of an opportunity and time window to intervene with drugs, and at least try to maintain the stability of the condition and prevent the transition to more severe forms of dementia.”

4

It was a finding so weird, so against scientific convention, that the researchers who made it didn’t believe it at first. Studying million-year-old rocks thousands of feet below the Pacific Ocean’s surface, they discovered mineral concretions, rocks known as polymetallic nodules, were producing oxygen. That’s surprising because—just like you learned in middle school—most oxygen is generated by plants and plankton drinking in sunlight and carbon dioxide. But at 12,000 feet down, it’s pretty dark. And rocks are, well, rocks. The researchers, including BU biologist Jeffery Marlow, concluded the rocks created the oxygen with a process called “seawater electrolysis.”

“For the most part, we think of the deep sea as a place where decaying material falls down and animals eat the remnants. But this finding is recalibrating that dynamic,” said Marlow. “It helps us to see the deep ocean as a place of production, similar to what we have found with methane seeps and hydrothermal vents that create oases for marine animals and microbes. I think it’s a fun inversion of how we tend to think about the deep sea.”

5

A new COVID vaccine that protects just as well as existing options—but at a lower dose—has shown potential in a series of tests. Developed by a BU team that includes biomedical engineers and virologists, the vaccine uses a type of ribonucleic acid, or RNA, called self-amplifying RNA (saRNA). Like the widely used messenger RNA–based Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, the saRNA version teaches the body how to fight future infections. But unlike those vaccines, the new vaccine keeps repeating its instructions, giving the immune system an extra boost and ensuring it can fight viruses for longer. The BU team has already demonstrated the vaccine’s effectiveness in mice and said the technology could even have potential in treating cancer.

6

If you’ve ever had a dark bank of cloud chill what had seemed an ideal beach day, spare a thought for our early human ancestors. About two million years ago, our solar system encountered a dense interstellar cloud that likely compressed the sun’s protective plasma shield, known as the heliosphere, robbing Earth of its protection. According to BU-led research, that likely left the planet exposed to radioactive particles and probably sent temperatures falling. “This paper is the first to quantitatively show there was an encounter between the sun and something outside of the solar system that would have affected Earth’s climate,” said BU space physicist Merav Opher, lead author on the research.

7

Meet MAMA BEAR. For more than three years, this dogged robot has been on the hunt for the most efficient energy-absorbing shape to ever exist. It prints a small plastic shape, smashes it, measures its absorption capabilities, tweaks the design, and repeats the process. Again and again and again. So far, it’s printed more than 25,000 shapes and, this past spring, the team behind it—led by BU mechanical engineer Keith Brown—announced MAMA BEAR had broken the known record for energy absorption. The findings could help produce better car bumpers, helmets, packaging, and other safety gear. And even though MAMA BEAR has made history, it’s still printing and smashing, trying to break its own record.

8

For the second year in a row, college student mental health has improved, according to a study coled by BU public health researcher Sarah K. Lipson. The Healthy Minds Study of 100,000-plus US college students found symptoms of depression, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide had declined, and that more young people were connecting with mental health care and support. But the team’s survey also highlighted many areas of concern, including a high prevalence of mental illness among college students and a large proportion of students reporting feelings of isolation. “While I very much hope that we will continue to see improvements,” said Lipson, “we will need a few more years of data showing changes in the intended direction before we feel confident pointing to a definitive trend.”

9

After studying the remains of enslaved people who died on the remote Atlantic island of Saint Helena, BU bioarchaeologist Andreana Cunningham was able to paint a more complex picture of their lives and where they came from than was previously known. She found a greater influence of southeastern African populations among existing African diaspora populations along the Atlantic. Much of our existing knowledge of where people were captured from is based on the (sometimes obscured) records of enslavers. Cunningham’s goal is to restore the agency and stories of people who were enslaved through a combination of bioarchaeology, African diaspora studies, and archival research.

“The skeletons of the past can actually tell us a lot about the history of the individual they belong to,” Cunningham said. “The experiences that you go through can be marked on your body, literally. Things like stress, daily habits, nutrition, the places you come from—these are all things that can be recorded, to some extent, on your skeletal remains.”

10

In a special series, The Brink examined BU’s pioneering work studying chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). The University’s researchers have pinned repetitive head impacts—particularly from contact sports like football and ice hockey, but also from military service—as causes of the progressive brain disease. In addition to studying how CTE changes and damages the brain, they’ve also helped shape a national conversation on sports safety and brain injuries, making BU the world’s foremost seat of research into the disease. For now, CTE can only be diagnosed after death, but BU researchers are starting a major new project that could help clinicians spot it in life—the first step in pioneering new treatments.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.