POV: Yes, Filling Out the Race Box on Forms Is Tiresome, but Here’s Why It Matters

To root out racism, we need to talk about race even more than we already do

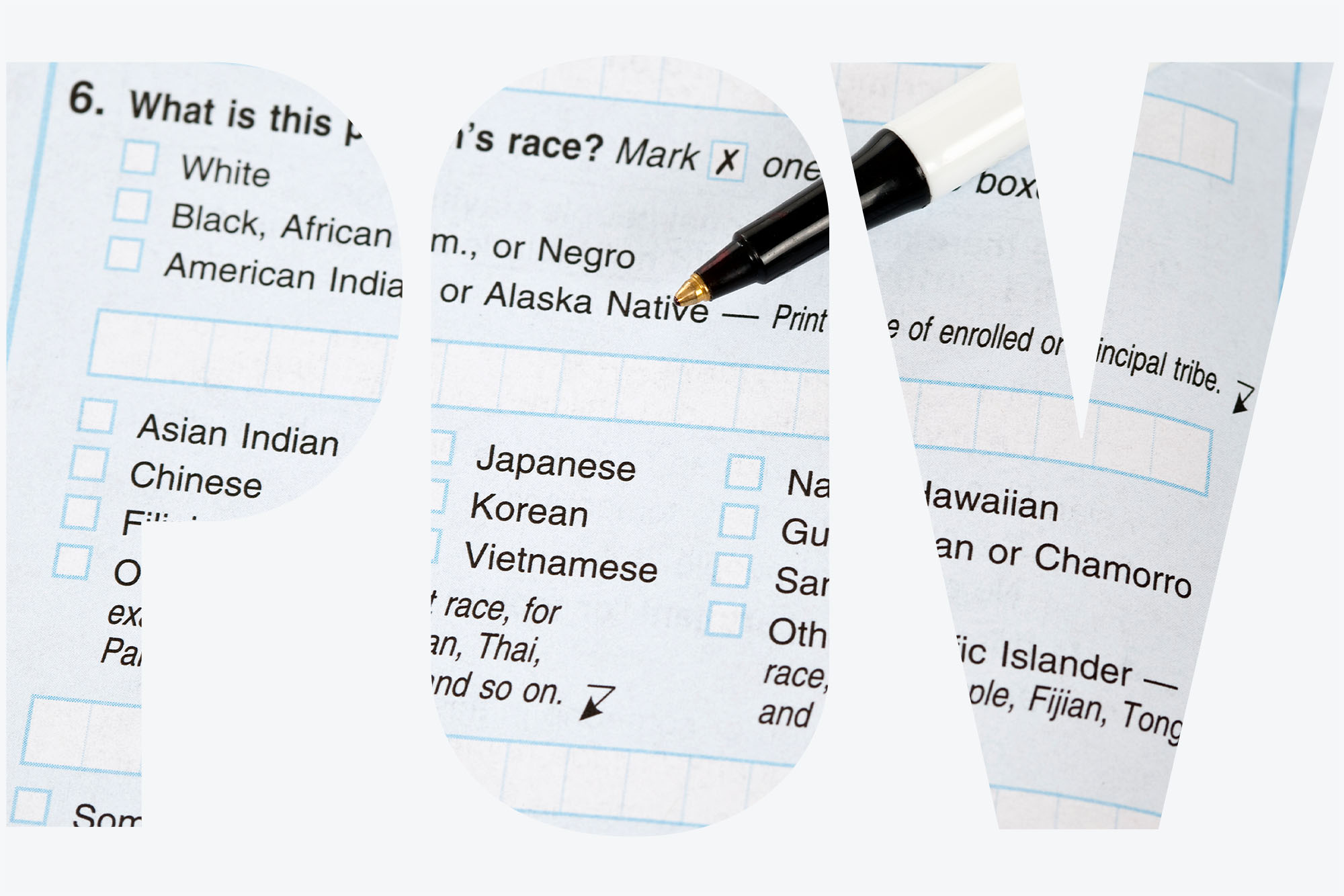

Photo by blackwaterimages/iStock

POV: Yes, Filling Out the Race Box on Forms Is Tiresome, but Here’s Why It Matters

To root out racism, we need to talk about race even more than we already do

Filling out your race and ethnicity on a form may feel tiresome, and even uncomfortable. You have been checking these boxes for years, as has everyone else, and the questions may seem irrelevant.

“What does race have to do with my doctor’s appointment?” you might ask. Or a form may be inaccurate: “I’m Middle Eastern, why don’t I get a box to check?” Perhaps it feels intrusive: “How is this information going to be used?” And you may wonder, “Why are we always talking about race?”

The truth is, we need to keep talking about race. Even more than we currently do.

This isn’t because race tells us anything about how people think or act; it doesn’t. Race is not a fixed, biological fact but rather a social and power construct. We need to talk about it because we need to root out racism. We need to understand and document how people’s lived experiences differ based on how they are racialized.

Data is a powerful tool in understanding how racism operates, how resources are distributed, and how different racial and ethnic groups experience benefits or harms.

Data can uncover striking racial inequities and point to the need for specific policy changes. For example, at the start of the pandemic, many mischaracterized COVID-19 as the “great equalizer.” But the COVID Racial Data Tracker, a partnership between the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research and The Atlantic, showed the virus harmed Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities the most. This information was ultimately used to determine more equitable locations for COVID-19 testing sites and vaccine distribution.

Missing and incomplete data, lack of information that can be compared across time and geography, infrequently updated data, and other problems make the work of data scientists who are trying to study racism exponentially harder. This, in turn, directly affects people’s day-to-day lives.

The better the data the US Census Bureau can collect, the better that funding and policy can be tailored to identify and address inequities. The census undercount of the Black, Latino, and Indigenous populations is a case in point. The Trump administration caused confusion by attempting to add a question about citizenship, which likely discouraged a lot of people from participating in the census count.

Throw in the pandemic, natural disasters, and the legal battles, and you have the makings of an undercount. Undercounting a racial group by even a few percentage points will likely lead to funding cuts for critical public services, such as food assistance, healthcare, and housing.

The Latino population was undercounted by nearly 5 percent. Brookings Institution researchers say this discrepancy will likely mean the loss of tens of millions of dollars in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps) and the National School Lunch Program. Similarly, the most recent census did not count “nearly 1 of every 17 Native Americans who live on reservations,” according to the Idaho Capital Sun, which will affect “how much money is allocated to various programs on reservations, such as healthcare, social services, education, and infrastructure.”

Existing racial and ethnic categories used for data collection are far from perfect. They often conflate distinct racialized experiences or leave out entire groups altogether. They are often modeled on federal standards that have not been updated since 1997. Karin Orvis, the US chief statistician, recently announced a plan to update these standards by 2024. We have much to learn about how to best track data that captures racialized experiences, and how to achieve an appropriate level of nuance. Not collecting this data will set us back in our efforts to fight racism.

Talking about race is not racist. Collecting data on race is not racist. Ignoring the glaring reality that racist ideas are embedded into society only perpetuates racism.

Neda Khoshkhoo, associate director of policy at the BU Center for Antiracist Research, and Jasmine Gonzales Rose, the center’s policy chair and a professor at the School of Law, can be reached at nakhosh@bu.edu and jgrose@bu.edu, respectively. This column originally appeared in The Emancipator.

“POV” is an opinion page that provides timely commentaries from students, faculty, and staff on a variety of issues: on-campus, local, state, national, or international. Anyone interested in submitting a piece, which should be about 700 words long, should contact John O’Rourke at orourkej@bu.edu. BU Today reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.