I Will Teach My 10,000th BU Student This Summer. Here’s What I’ve Learned

Media via iStock/Yuoak/Volodymyr Kotoshchuk

I Will Teach My 10,000th BU Student This Summer. Here’s What I’ve Learned

Questrom’s Jay Zagorsky on what his students have taught him over 35 years of teaching

What is it like to teach 10,000 Boston University students? This summer, my 10,000th BU student entered one of my classrooms and I got a chance to reminisce.

To get to 10,000 students, four things need to happen. First, you had to have started a long time ago. I taught my first BU class as a new PhD student in the fall of 1987. Second, you have to teach a lot of classes. My spreadsheet lists 140 BU courses spread over Questrom School of Business, the College of Arts & Sciences, and Metropolitan College. Third, you need to teach large introductory and Core Curriculum classes. These giant classes have made me an expert in the audiovisual equipment and quirks of almost every giant lecture hall on the Charles River Campus. Last, you need to teach in programs with exploding enrollment. Being a core instructor in BU’s new online MBA program got me to the 10,000 student milestone years earlier than expected.

There have been many constants over the decades of teaching. BU students are still smart, curious, and a lot of fun to teach. Plus, while I have aged, my students are still young. Not everything is static, though.

I’ve seen the most change in four big areas.

Technology

First, technology has changed the teaching experience dramatically. My first classes in CAS were decidedly low-tech. I used chalk and I talked. Coming out of a long lecture I was so often covered with a layer of fine white chalk dust that I gave up wearing dark clothes to class.

To improve the technology in those first classes, my wife bought me a box of colored chalk. This first experiment in going high-tech was a total failure. I am partially color-blind and couldn’t tell the chalk colors apart.

Then in the early 1990s I tried another technological advancement: communicating with students via a new tool called email. As an incentive to use this new tool, I provided my lecture notes after each class to anyone who gave me their email address. Many students, surprisingly, avoided using this new technology at first because most thought it would decrease the amount they learned. This lesson is useful to keep in mind as artificial intelligence remakes our classrooms.

My third try at technological change was more successful. In my early years of teaching, there was constantly a line of students outside my office door who missed a class and wanted a one-on-one review of the entire lecture. I spent hours doing the same lecture over and over.

I fixed this problem by taping all my lectures. I acquired a “portable” VHS video camera that was about the size of one that TV news crews use today. I dropped the tapes off in the reserve section of the library, so students could watch the lecture. I must have been onto something, because about 20 years later the University began automatically recording lectures with small cameras mounted in the classroom ceiling.

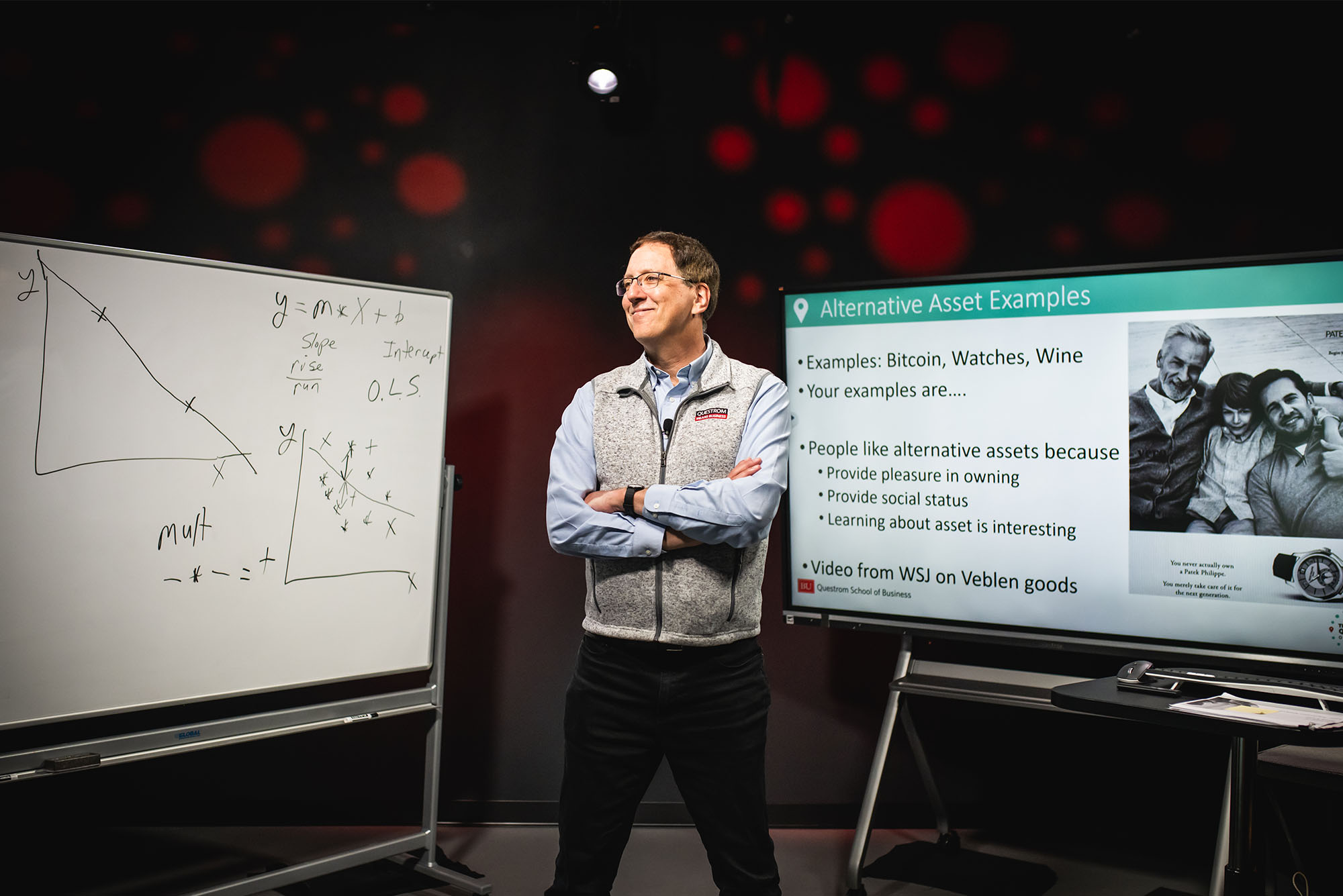

An unexpected benefit of the recordings was how it made me comfortable being in front of a camera. This came in handy when BU created its online MBA program, which includes televised sessions held in BU’s new Kenmore Square studios. Giving a studio lecture is like being the host on a TV talk show. There is even a four-person crew handling the technical parts and audience questions.

Exams

When I first started teaching, exams were low-tech affairs using blue books, small paper pamphlets with about 20 lined pages that students filled with longhand answers.

It took time to hunt down where answers were written since not everyone went through exams linearly. To fix this problem, as photocopying prices dropped, I shifted to printing out exams where students wrote their answers in a space directly below the questions. This worked better. But copy machines often broke just before exams and when I taught giant undergraduate classes it often took a small team to carry the boxes of exams.

The next step was switching to computerized exams. This reduced the massive amounts of paper being wasted and made it easier to read student answers, since, thanks to technology, handwriting is getting progressively worse over time.

Computer exams came with their own set of problems, since not every student had a laptop. In the beginning, students with laptops took the exam in the classroom and those without went to a computer lab. Proctoring was a nightmare when students were physically split up, but I got a lot of exercise jogging between locations.

When COVID-19 struck, BU and all exams went remote. To prevent cheating, students turned on their computer’s camera and took exams while on Zoom. Proctoring on Zoom wasn’t that effective at preventing cheating since it was impossible to know what a student was doing while hunched over their keyboard.

Today most exams are happening back in the classroom. While most of my exams are done using computers, for small classes I occasionally go back to paper and pencil, since it’s harder for tech-savvy students to cheat with an old-fashioned exam.

Grading

I have seen, and I have participated in, grade inflation. In my first semester I taught 64 students in two sections. In one section I gave only one straight “A” and in the other section the highest grade was “A-.” Over 40 percent of grades were “C+” or lower.

Today my grade distributions are higher and I hand out more “A”s. Higher grades do not eliminate grade disputes. In the old days, students who were in danger of failing often came to dispute their grade. Now more grade disputes are from students with very high scores.

I recently gave one student an “A-.” Instead of complaining to me, my department chair, or the dean, they went right to the BU president’s office. While going to the president is unique, many grade disputes are now with people furious that they did not earn a straight “A.”

Students

I have taught many fascinating BU students over the decades, from princes to paupers. I love hearing about their lives, which has provided me with stories that I could never learn from a book or journal. Not only have the stories changed over the years, but so has the student composition. In the 1980s many of my students were from the Northeast. In my first class, there was a woman from rural Kansas, an exotic place to most of us in New England. Today, my students span the world.

During my online MBA sessions I talk to students in six out of seven continents. I haven’t yet taught anyone living in Antarctica, but there is still time before retirement. Talking to students in far-flung locations is often seamless. Last year, I took a question from an online student running a refugee camp in Sudan. The audio and visual clarity were perfect. The next student was in California. Their internet connection was so spotty, they ended up typing their question into the chat box.

Not only are students coming from more locations, their genders and identities have shifted. Judging gender by people’s first names (hardly an exact science, I recognize), my earliest course had more men than women, while in my latest face-to-face class it appears there are roughly two women for every man.

What have I learned?

My students over the years have taught me a huge amount about subjects from A, like cutting-edge apps, to Z, working near a war zone. But three lessons in particular stand out:

First, always have a backup plan. Technology is great, but when the electricity fails, the internet goes down, the class website crashes, or the projector dies, you need to be ready to pivot. In simple words, use technology, but learn how to use older, simpler analog methods.

Second, never assume your audience, friend, or spouse completely understands what you are saying. I once taught a group of Korean students how to predict the future sales of “hammers,” as in the tool used to hit nails. The puzzled faces showed me the lecture was bombing. As a native Bostonian, whose grandfather and mother both graduated from BU, I am proud of my roots and my accent, which includes not pronouncing the letter “r.” These students understood the math I was teaching, but they had no idea what a “ham-mah” was, at least not until one was brave enough to ask for a picture of what I was saying.

Third, if you want someone to really understand your point, tell them a story. Facts, figures, and theories are all fine—but what alumni tell me they most remember are the stories that I told to explain topics.

On that note, here’s a story: about a decade ago I had acute appendicitis just before a class. I was rushed to the operating room and before the surgeon cut me open, the anesthesiologist leaned over and said, “Think of the place you most want to be, like the beach.” The image I saw before being knocked out was me giving a lecture in Morse Auditorium in front of a sea of BU students. So far that sea has included roughly 8,000 face-to-face and 2,000 online students.

While I hope not to be rushed into an operating room again, I don’t think my vision of where I most want to be has changed. I look forward to teaching and learning from my next 10,000 Terriers.

Jay Zagorsky (GRS’87,’92) is a Questrom School of Business clinical associate professor and a lead instructor in BU’s new Online MBA program.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.