From Wheelock to Washington

Associate Professor Joshua Goodman is spending a year with the Biden administration’s Council of Economic Advisers

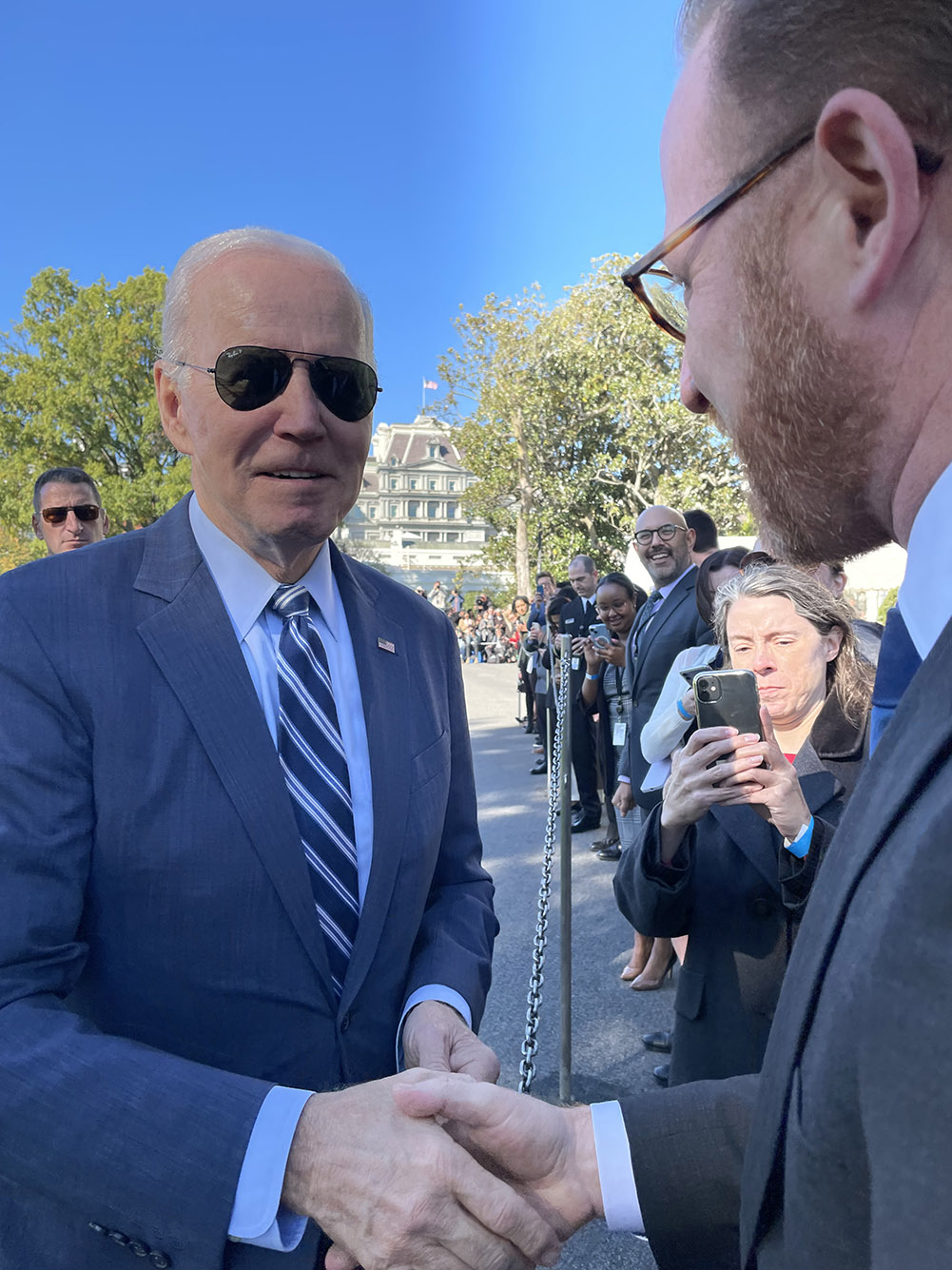

Working in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building next door to the White House, Goodman is sometimes invited to join a rope line and shake hands with Joe Biden when the president leaves to board the Marine One helicopter. Photos courtesy of Joshua Goodman

From Wheelock to Washington

Associate Professor Joshua Goodman is spending a year with the Biden administration’s Council of Economic Advisers

For the last year, Joshua Goodman has been up at 5 am every Tuesday to catch a 7 am flight to Washington, D.C. By 9 am, the Wheelock associate professor of education and economics is at his desk in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the White House.

“It’s a credit to JetBlue and the D.C. Metro system, which is a little more functional than the MBTA,” says Goodman, who returns home to Cambridge every Thursday evening.

On July 14, Goodman wraps a yearlong stint as a senior staff economist on the Biden administration’s Council of Economic Advisers, lending his expertise on topics such as higher education funding and student debt.

“My office window looks out on the White House and the West Wing, which is pretty darn exciting,” he says.

He has yet to be invited next door in a professional capacity; meetings with President Joe Biden and his senior advisers are typically handled by the three council members. Goodman and other staff economists crunch the numbers, carefully parse policies and their projected effects, and advise the council and other administration officials on what they find.

“We talk to the people designing the regulations or policy proposals, and we sit and read through them really carefully,” he says. “It could be the text of the regulation or what are called regulatory impact analyses, which are a little bit like cost/benefit calculations. We try to understand if we think they’re capturing the benefits and the costs of this particular initiative correctly.”

Key projects in recent months include reviewing reforms to income-driven repayment of student loans from the federal government. “This is the idea that if your income is sufficiently low, and it’s causing you trouble repaying your loans, you can enroll in a program that might lower your monthly payments,” Goodman says. “The administration put forward a plan to basically make it substantially more protective of low-income borrowers.”

Another important task has been helping the Biden administration reshape two requirements that must be met by schools participating in the federal financial aid program: that students graduate with a level of debt that doesn’t exceed a certain fraction of their earnings, and that they reach a certain level of earnings.

“If the average graduate of your program is earning less than a typical high school graduate in your state, we take that as a sign that something is going wrong with your training and perhaps [the program] should be cut off from the federal financial aid system,” he says.

Generally, Goodman says, the council economists are working to balance the desire to help student borrowers and the program’s budgetary cost. “We try to help the administration understand what the trade-offs are.”

He works remotely from Cambridge Mondays and Fridays, and is in Washington, D.C., Tuesdays through Thursdays. “If it had been five days a week in the office, I’m not sure I could have taken this job, because I wasn’t going to uproot my wife, who works for the Massachusetts attorney general, and my three kids, who were very happy in their Cambridge public schools.

“And so, at the ripe old age of 44, my dream has come true,” he says with a smile. “I am living on a pullout couch with my in-laws.”

The Biden administration is also interested in the fact that some school districts are struggling to hire teachers. Goodman and his colleagues have tried to make projections about the future of the teacher workforce.

Goodman, who is in his third year on the Wheelock faculty, was asked to take the job by email a year ago. He says he’s grateful to Wheelock Dean David Chard for allowing him to take a year’s leave. As there is no government appropriation for a salary, Wheelock has continued to pay him while he serves as a senior staff economist.

“I feel very strongly that if he has been paying my salary to do this service work,” Goodman says, “then I’d better bring that value back next year and make it worth it to the institution.”

My kids, I think, got the impression that the way I start my day is to meet the vice president and chat with her.

Among the concrete benefits, he says, is a much clearer and more comprehensive sense of what the federal government is working on in both higher education and K-12 schools. “I think I can speak much more intelligently about a number of federal policies and regulations than I could a year ago, and I hope that will come across to my students.”

He also has a much better understanding of how education policy and legislation are produced. “When I was coming into the job, I had some naïve vision that if we have a policy decision to make, all the smart people are gonna get into the room and hash it out over the course of the day, and the best thing is going to come out at the end of that,” he says. “Obviously, that’s not really how it works.

“Someone comes in with an idea. Maybe they’re the first. Maybe they’re the loudest. And then what proceeds is a messy set of interactions between all sorts of interested parties trying to tweak that initial idea, shoot it down entirely, modify it.

“And it’s been educational for me to understand or to start to understand: how do you actually get power in those conversations? How do you find influence?”

It’s led him to consider integrating feasibility into his policy discussions when he’s back teaching at BU Wheelock. “I’ve never really been forced to say, ‘Let’s take 15 minutes [at the end of class] to ask, what if the politics doesn’t allow that thing? Is it obvious what the next best option is? Not just what’s the policy that’s best, but like, what’s the policy that’s best that we could actually execute?’”

There are fringe benefits too.

Goodman was present when the president spoke to council staff after they submitted an annual economic report. He was able to bring Yunee Yoon (Wheelock’26), a Korean student in Wheelock’s PhD program, to a White House event for the president of South Korea. And he gets occasional invitations to events on the White House grounds, such as a lottery for one of the spots on a rope line to shake the president’s hand as he leaves or arrives on the Marine One helicopter.

“That was very fun. I got to pet Commander,” one of the Bidens’ dogs.

Goodman’s wife and children came down for a tour last October, and the Secret Service directed them to stand back from an elevator bank in the Executive Office Building as Vice President Kamala Harris arrived.

“She sees my family waiting and walks off her path over to us, and bends down to my kids and says, ‘Who are you and what are you doing?’ And my kids told her who they were. And I’m standing there holding my dry cleaning in one hand and stammering like a fool, ‘I’m an economist.’ I couldn’t even get the words out. Didn’t get a picture. But my kids, I think, got the impression that the way I start my day is to meet the vice president and chat with her.

“That is a rare occurrence, but it was very sweet of the vice president to do, and definitely a moment that we will all remember.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.