Hollywood Strikes. BU Acting Alums Explain Why Their Fight Matters

Photo by Emma McIntyre/Getty Images

Hollywood Strikes. BU Acting Alums Explain Why Their Fight Matters

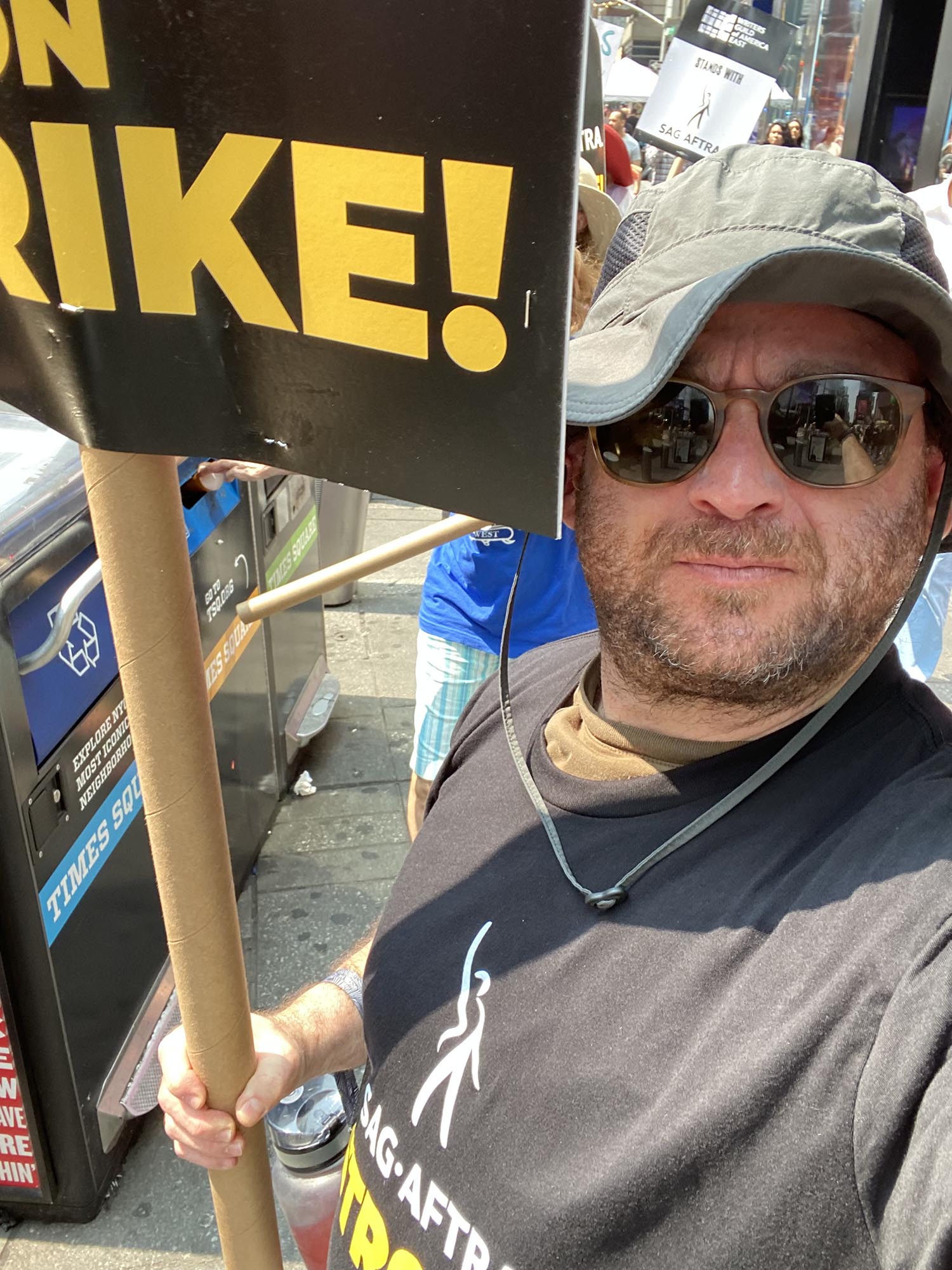

“We as a society need to choose if we’re going to let corporate greed rule our lives or not,” says CFA alum and actor David J. Castillo

The irony is that it’s precisely the kind of feud that would make for a scripted TV drama series. The only problem is that there’s nobody available to write it, direct it, or act in it. They are all on strike.

Two months after the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike, demanding and failing to get a better contract from Hollywood studios, the Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) is following the same path. Their contract expired at the end of June. It’s the first actors strike since 1980 and the first time since 1960 that writers and actors have simultaneously been on strike.

Hollywood is shut down. Productions are shut down. Even promotions for current movies and shows are shut down. Actors, similar to writers, are focused on three main issues: fairer wages for those at the lower end of the pay scale, control over use of artificial intelligence (AI) (in this case, not allowing your likeness be used to create new programs without your involvement and compensation), and improved residual payments in the ever-expanding streaming world.

Boston University has a number of alumni who are actors working in Hollywood. After the SAG strike vote was called July 13, BU Today spoke with four of them. There was unanimity in their anger and frustration, their belief in the cause, in the necessity of the strike.

“If not now, when?”

“If not now, when?” says Dave Shalansky (CFA’96), who’s acted in Grey’s Anatomy and Gilmore Girls. “We have been dormant long enough. Perhaps too long. But we can’t harp on the past. The time to strike is now. There is too much at stake.”

“We as a society need to choose if we’re going to let corporate greed rule our lives or not,” says David J. Castillo, (CFA’17), who had roles in The Rookie and Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania. “And I’m happy my union decided to say no.”

“There is nothing else we could do,” says veteran actor Michelle Hurd (CFA’88), most recently featured as Raffi Musiker in Star Trek: Picard.

Hurd is a member of the committee that had been trying for 35 days to negotiate with the studio consortium, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). “The negotiators did not lose their cool,” she says. “I’m so proud to be part of this committee. If you’ve heard that SAG-AFTRA has been divisive, we had no divisiveness here. We came together and dropped our differences at the door—we have one enemy and that is the AMPTP.”

Hurd spent much of July 17, the day BU Today talked with her, on picket lines in New York outside 30 Rock and 1515 Broadway in 90-degree-plus heat. “I’m exhausted, but it was fantastic,” she said later that night.

She was still full of fire. “So many actors rising to the occasion! It was packed with actors and writers. Cars were beeping their horns. The energy is very powerful, and we all know we’re on the right side of history on this one.”

“Existential threat” is the phrase many of the WGA strikers were using, especially as it concerned the studios’ use of artificial intelligence. That was also a key component of what Fran Drescher, SAG-AFTRA president, said at a news conference announcing the strike. She railed at the studios, saying, “AI poses an existential threat to creative professions.”

“We can’t survive,” Hurd says. “I’ve been an actor over 30 years, and when I graduated BU and moved to New York, I began acting. Never had any other job. I supported myself, and I take pride in that. And then 10 years ago, things started to change because of streaming, Friends starting calling me, saying, ‘We can’t make rent, we’re falling off [qualifying for] insurance.’” (Actors need to make $26,000 a year to qualify.)

Hurd says that before the ascendance of streaming, things were mostly good. “But a new business model was forced upon us. When we had linear episodes, it was a cash cow—everyone was winning. But with streaming, you’d work for four to five months for 20 episodes and the studios would take years to inform their actors if the show would be picked up and if they would be picked up. We were not allowed to take other series.

“Residuals from streaming disappeared and completely changed the script of how we made our living. The streamers want to tell us their business model was not what they thought it would be, but that’s on them. For us to contort ourselves to fit into their [world] is insidious, condescending, and gross.”

Baron Vaughn (CFA’03) played Nwabudike Bergstein on Grace and Frankie, the adopted son and lawyer-to-be during the show’s eight-season run on Netflix. The timing of the strike, he says, “is indicative of the fact that everything is backwards: the people who created the content do not feel they’re being valued. The tech takeover means that everybody is doing a lot more for a lot less. It’s the tech ethos, which tends to devalue labor. Like Elon Musk said when he took over Twitter, [you have] to be hard-core for very little compensation.

“I was on Grace and Frankie long enough to see Netflix change three different times,” Vaughn says. “It was an interesting thing to see Netflix as a fledgling company becoming the master of all of Hollywood. Then, at the last company function for that show, after the news that Netflix had lost subscribers, I saw the beginning of the writing on the wall. The reality we’re seeing started about that time.”

Big stars making noise

Although both strikes are happening simultaneously, the SAG strike may resonate more with the general public. It doesn’t hurt to have the big stars make noise. Before the vote to strike was taken, Cambridge-raised megastar Matt Damon, while on a promotional tour for Oppenheimer (which opened this weekend), told the Associated Press: “What we would be striking for, if we strike, is unbelievably important. We got to protect the people who are kind of on the margins.”

Damon cited that $26,000 year minimum: “Residual payments are what carry them across that threshold. If those residual payments dry up, so does their healthcare, and that’s absolutely unacceptable.” Like all the stars, Damon cannot do any more promotion during the strike.

Yet they were able to do exactly that during early July—for Oppenheimer, Barbie, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, and Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part One—when the AMPTP negotiated for a 12-day extension of the bargaining time frame. (The Oppenheimer stars did walk off the red carpet in London just prior to the strike. According to director Chris Nolan, they were “off to write their picket signs.”)

What Hurd saw ultimately, she says, was deceitful gamesmanship on the part of the AMPTP. They failed to discuss issues until the very end, coming back on the last day, she says, and offering “a partial response to a proposal on AI.”

Why did they do this? The timing of the strike came just as the Barbie and Oppenheimer blockbuster weekend was approaching.

“They wanted the movies this summer to have their red-carpet premieres,” Hurd says.

There’s a meme that’s been circulating since the strike began. Images of actor Linda Hamilton as Terminator heroine Sarah Connor juxtaposed with that of Fran Drescher as the big-haired title character in The Nanny. Under Hamilton: “The woman we thought would lead the rebellion against the machines” and under Drescher: “The woman who ended up leading the rebellion against the machines.”

“Fran has been outstanding and such a powerful force. AMPTP underestimated her,” Hurd says. “She said, ‘I’m not gonna let you bully us anymore’ and she was intimidating.”

Disney CEO Bob Iger framed the battle in terms of “disruptive forces” roiling the industry and coming so soon after the COVID-19 pandemic/economic catastrophe: “This is the worst time in the world to add to that disruption,” he said.

Drescher called Iger’s comments “repugnant,” and said he, along with other CEOs, were prioritizing their own wealth and were like “land barons of a Medieval time.”

Castillo echoes the “existential” reasoning, but says that it was “not just for actors and writers, but for working-class people in all industries. People are tired of working their asses off and barely scraping by while those benefiting from their labor get paid hundreds of millions of dollars a year.”

There are stories of actors walking off sets as the strike bell tolled. “I would have loved to have walked off a set,” Vaughn says. “I’m very dramatic and would have loved to.”

“If I was lucky enough to be working this year, I could only imagine that the feeling is empowering,” Shalansky says. “I have been a working actor for over 27 years and residuals are now literally pennies. It’s more than just a shame—it’s life or death. Surviving as an actor is so hit-or-miss, and every job is so hard to come by. I can only assume the feeling for those who do walk off must be terribly bittersweet. But almost 98 percent of us are working journeymen actors, and we know all too well that we all need to support each other and this strike.”

This leads to one of the myths SAG-AFTRA strikers would like to see busted: a perception that because they may have roles on TV shows or movies, they are all multimillionaires in positions of privilege. If anyone confronted him with that position, Shalansky says, “I wouldn’t respond. I’m not fighting for them. I’m fighting for me and my family and the future of my craft.”

“Anyone who says that these strikes are for the wealthy actors who just want more is factually incorrect,” Castillo adds. “It’s for the rest of us.”

“All the TV shows everyone watches, we are the working men and women, working-class actors,” Hurd says. “People see the shined-up, polished, produced part and see big stars in magazines, but the truth is, this is a business and we’re businesspeople, working hard for every paycheck.

“We all love what we do,” she continues. “It’s in our body and soul and I’m happy I love what I do, but that doesn’t mean we should be taken advantage of and bullied into accepting contracts below minimum wage in our industry.”

Standing strong and resilient

How long might the strike last? There have been predictions it will last into the fall or even extend into next year.

“I have no expectations,” Castillo says. “I hope that my union and the WGA stand strong and resilient in what we’re asking for. In an ideal world, this would end as quickly as possible. That said, I’m here for the long run if needed.”

Vaughn takes a long pause before answering. “I see it going the rest of 2023,” he says. “It’s hard to guess at it, but I have a feeling we’re in for the long haul. The WGA and SAG-AFTRA are respectively very far from the goals of the AMPTP, and as long as they’re on different pages, this is going to go on. It seems they’re not willing to budge and that’s why we’re in this situation today.”

Hurd considers herself “pessimistically optimistic. I believe if you don’t have hope, there’s no moving on to tomorrow. I am hopeful they will realize the error of their ways and do the right thing.”

“I think Fran said it well,” Vaughn says. “This is a system, a way of doing business that’s been foisted upon us and they expect the contract to stay the same, which is kind of cray-cray. She was speaking for all of us. There seems to be no respect here, and when there’s no respect, there’s no negotiation in earnest. What’s the point of this? They broke the system and are [still] making a ridiculous amount of profit from it. They broke it, they gotta fix it.”

“It’s strange to compare different industries,” Vaughn says, widening the scope, “but it’s also indicative of how unions have been demonized over the last couple of decades. People have been fed the idea you don’t bite the hand that feeds you—that in all times it should be participation and gratitude. Americans should not be taken advantage of. Across the board.”

Jim Sullivan (COM’81) is a Boston-based freelance writer who writes frequently about music and the entertainment industry. He is the author of Backstage & Beyond, Volume 1: 45 Years of Classic Rock Chats & Rants, Trouser Press Books, 2023.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.