Can the Play Common Ground Revisited, about Boston’s Busing Crisis, Reach 21st-Century Audiences Like the 1985 Book?

BU dramatist Kirsten Greenidge is daring us to find out

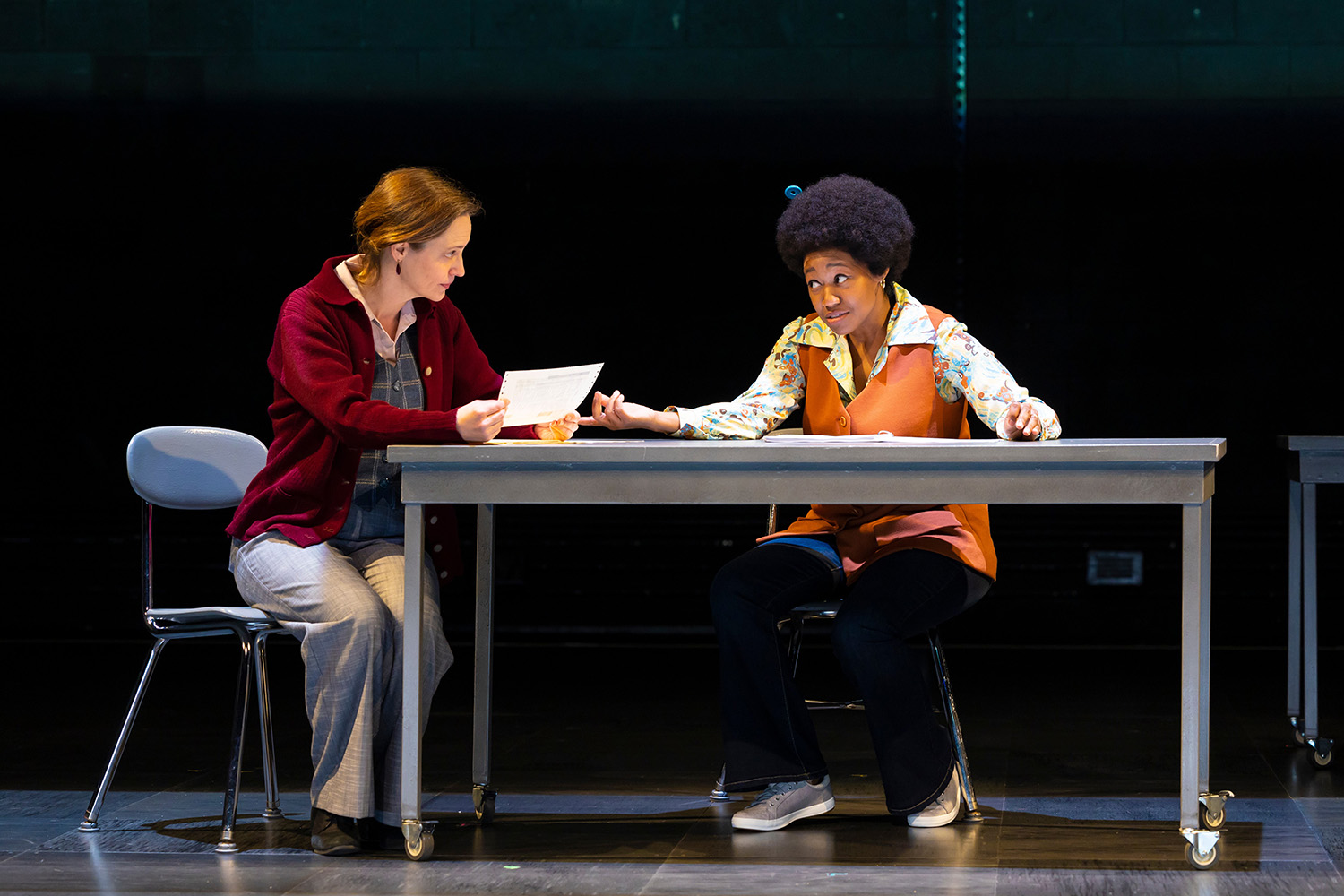

BU playwright Kirsten Greenidge (above) has adapted, with Emerson College theater director Melia Bensussen, Tony Lukas’ 1985 Pulitzer Prize–winning book Common Ground for the stage. The Huntington Theatre Company production of their piece, Common Ground Revisited, is playing at the Calderwood Pavilion Wimberly Theatre through June 26. Photo by Cydney Scott

Can the Play Common Ground Revisited, about Boston’s Busing Crisis, Reach 21st-Century Audiences Like the 1985 Book?

BU dramatist Kirsten Greenidge is daring us to find out

In his acclaimed 1985 book, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Anthony Lukas chronicles Boston’s battle over court-ordered busing to desegregate schools. It’s a portrait of a city, and a nation. “To say that Common Ground is about busing in Boston is a bit like saying Moby Dick is about whaling in New Bedford,” Robert B. Parker (GRS’57,’71) wrote in the Chicago Tribune.

But Lukas wrote his masterpiece nearly four decades ago—before the gradual resegregation of America’s public schools. Now, playwright Kirsten Greenidge, a College of Fine Arts associate professor of playwriting and theater arts, and Emerson College director Melia Bensussen have refashioned Common Ground into a drama for 21st-century audiences—and refueled it with present-day racial experiences and reflections on Boston’s history.

Greenidge, who the Boston Globe calls “one of the city’s leading dramatists,” has written and produced a dozen plays, among them The Luck of the Irish, which was premiered by the Huntington Theatre Company in 2012 and was directed by Bensussen. Greenidge’s play Our Daughters, Like Pillars finished its Huntington run at the Boston Center for the Arts (BCA) in early May 2022.

Greenidge and Bensussen have both won Obie awards for their work. Their new play, Common Ground Revisited, was years in the making. Greenidge says what began as a script aimed mostly at dramatizing the facts in Lukas’ book evolved over many workshopping sessions into something riskier: a play that’s based on those facts, but reimagines how some of the key characters might have crossed paths and makes use of cast members’ 21st-century racial experiences. Six of the actors are Black; six are white.

Lukas built his book around painstaking research on the Irish-American working-class McGoff family, the Black working-class Twymons, and the Yankee Divers—and how they experienced the battle over busing. Greenidge and Bensussen were able to tap unpublished material in the myriad interviews and notes for Common Ground that Lukas left behind. The acclaimed author and journalist, who struggled with depression, died by suicide in 1997, at age 64. His widow, Linda Healy, gave the playwriting team access to his papers.

“We’re holding up a mirror to this city and to this moment,” Bensussen told the Globe. “We are using this brilliant work of history as a point of discussion, of conversation.”

Common Ground Revisited was days away from its Huntington Theatre Company opening at the BCA’s Calderwood Pavilion—an event delayed for a year by the pandemic—when BU Today talked with Greenidge.

Q&A

with Kirsten Greenidge

BU Today: Can you talk about how this project evolved for you and Melia Bensussen?

Greenidge: Melia began this journey 10 years ago when she was in conversation with Rob Orchard [then Cambridge’s American Repertory Theater managing director, now retired from ArtsEmerson]. Rob loves this book and wanted to see if anyone wanted to adapt it. Melia said, “I would love to adapt it. However, I want to make sure we’re not deconstructing the book, but talking about how it fits into our culture now as opposed to just a straight up adaptation.” And we were also beginning work on Luck of the Irish here at the Huntington, which deals with some of the same themes. Another theater company had approached me to adapt it [Common Ground] about 15 years ago. So Melia invited me to adapt the book with her.

But the first thing we did was we worked on a class together at Emerson, an adaptation class that looked at the book, and had the students develop the pieces. It was really a wonderful semester, examining the book. And at that point some of the key players in Common Ground were still alive. And so the students interviewed some of them, and they interviewed people who lived in the three neighborhoods.

BU Today: And then what happened? Did the two of you start writing scenes?

Greenidge: Lots of conversations—with myself, Melia, our dramaturge Charles Haugland here at the Huntington. They had a dramaturge team all working on this book. So we’d get together for workshops. A lot of those in the last few years have involved most of the current cast members. So it’s been great to watch them approach the material and read and research and look up in archives and things like that.

But Melia and I figured out, what do we want to highlight in the book? And it’s had many iterations. We played with whether to have the same ending as the book. How should the story end? I will say that it didn’t have a definitive ending until last week.

We also did a number of interviews that we drew from. And we drew inspiration from that first class.

What’s astounding about the book is how much research Lukas did. And a lot of it ends up in the book. But it’s interesting to see what he was able to include and how he summarized or encapsulated certain conversations. He was a very complicated, brilliant man. And it’s fascinating to step into his process, his research. I joke that we could probably have worked on this for 10 more years.

BU Today: How did you relate to the book?

Greenidge: I was very interested in how Tony researched the three families. At the time, to see that kind of research about a Black family was amazing. Not many of us know that much about our ancestors. It’s not until the last few years where you have ancestry.com or 23andme. So I was enamored by that. I grew up under the umbrella of Alex Haley and Roots.

BU Today: Do you think a lot about how Boston has changed since that time?

Greenidge: I do, because there are so many different lenses: of who tells history, who speaks history, who researches it, and whose work gets honored. And that has shifted since 1985 and ’86. So there are other voices, other movements connected to desegregation in Boston and in the busing crisis, other authors who have written since then. This book has touched so many people, and it’s so wide and sweeping, and it reads like a novel even though it is not. I’m really beginning to appreciate not just Lukas’ work, but also the work of the people who came after, that this book might have inspired—whether they were really enamored with the book or it made them angry and they had something to say to the book.

I grew up in the shadow of busing. I was four when I said something really wrong to my mom, like, “Oh, St. Patrick’s Day is coming up. Should we go to the St. Patrick’s Day Parade?” And she said, “No.” And I was like, “What!? Why not?” I had no idea. I did not understand my mom’s trepidation at venturing into South Boston for the parade, or to Charlestown for Bunker Hill Day.

And that’s when she began to explain to me a little more about the history and how sheltered in some ways we were able to be. I remember that conversation—her discussing Boston neighborhoods, how they differ a little bit from each other, and the way those neighborhoods are divided. And I remember thinking, oh, OK, I think I understand a bit more. So when I read the book, I was just like, oh, I understand.

BU Today: Schools are so central to this story. Can you talk about where you went to school?

Greenidge: I went to public school for first and second grade. And because of Proposition 2½ [a 1980 Massachusetts law that limited property tax increases, effectively cutting cities’ and towns’ school funding] and the school shutdown, and a racial incident I had at school—that combination of things had my mother searching for a private school. And through financial aid I went to a Quaker school in Cambridge. And then I ended up graduating from Arlington High.

BU Today: Could you talk about the racial incident?

Greenidge: A [white] student kicked me. An older student. I was in second grade. I remember thinking, I know why this student kicked me. I was in the lunchroom, and I think I dropped something—I bent down, and he kicked me in the back. I don’t remember physical hurt. I remember the emotional hurt and the deep shame.

I told my mom, and I just begged her, “Do not tell anyone,” because I felt shame, as opposed to, like, “Don’t do that.” And she listened to me. And she knew, and felt a sense of agency with, the principal. He had the boy come and apologize to me—which to me was even worse. But years later, I came to appreciate not only her actions, but the principal’s as well.

BU Today: Did that help you understand what the kids who were bused went through?

Greenidge: A little bit. Lukas has amazing stories of Charlestown High teachers that I strove to include, teachers who care, and teachers who are caught up just as much in that really difficult, fraught time. Teachers who feel like, oh, I understand what your background is, where you’re coming from. But this is still wrong to treat a child this way.

I mean, I’m sure many kids of color can name terrible incidents that have happened to them in school growing up, but I really think mine are relatively few. So while I’m able to, like, think about what these students went through in South Boston, in Hyde Park, in Charlestown, I know I had the privilege of going into classrooms where people wanted to see me succeed, and did not want to see me hurt. And I cannot say the same for some of the students in these classrooms—which is the heartbreaking part.

BU Today: The play includes a conversation between a Black student, Cassandra Twymon, and a white student, Lisa McGoff—Twymon was bused to McGoff’s high school, in Charlestown—that isn’t in the book. Can you talk about that?

I think part of my job is to, like, figure it out. Okay, so there are these two people in the book, but in separate chapters—the Twyman and McGoff families. It took me years to see, oh, right, they are occupying the same space. And what would it be like for these two students to meet each other?

Cassandra and Lisa were both active in school life—things like yearbook, graduation. And while the scene we have did not actually happen, my feeling is, okay, how and what might those interactions be like?

In an ideal world, these two young women—in my ideal world—would be able to go to the same school and talk with each other and delight in each other’s successes. That obviously was not able to happen. But I think to be able to wish for that world where it could, I have to be able to imagine it, and show it to other people.

That scene came relatively late in the process. For a long time, I was writing much longer scenes and dramatizing the book piece by piece. And we realized, oh, right, we can’t do it this way. Because we’ll be here for three days! And as much as people love Common Ground here, we cut. We figured out what we wanted to focus on, what’s important to us.

A lot of our workshops for the past few years have been bringing in bits of scripts, bits of scenes, and then talking with the actors about their experiences living and working in Boston—getting to know what were their experiences going to school. Focusing on Cassandra and Lisa also allowed us to find this commonality—common ground, if you will—that of an entry point into our ensemble members’ lives, as well as the lives in the book, since the play is set both in the time of Common Ground and today.

BU Today: You said in an interview that you’re always somewhere in your plays, in a character. Where are you in this play?

I can see myself definitely in Cassandra, in the Black family. But I would be remiss if I didn’t say I could see part of myself in Lisa as well. Particularly as she, you know, she works out what she wants for herself and for her classmates. And how she’s feeling as she navigates that—that change.

BU Today: Where are you going to be on opening night? Where do you watch? Backstage?

I’m not backstage. I don’t want to make my actors nervous, being in my own psychodrama about opening nights. So I usually request to be seated in the very last row of the house, away from everybody. My family sits somewhere else.

The Huntington Theatre Company production of Common Ground Revisited is at the Calderwood Pavilion Wimberly Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts, 527 Tremont St., Boston, through June 26. Tickets start at $25 and can be purchased online, at the Calderwood Pavilion box office, or by calling 617-266-0800. Find a schedule of performances and buy tickets here. Note: all patrons must present either proof of vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test to enter the theater, and masks are required.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.