Anger, Pride, Fear: BU’s Iranian Students React to Mahsa Amini’s Death

“This is not what the Middle East deserves” and “This is a revolution,” students say, responding to the killing of a young Iranian woman over her hijab

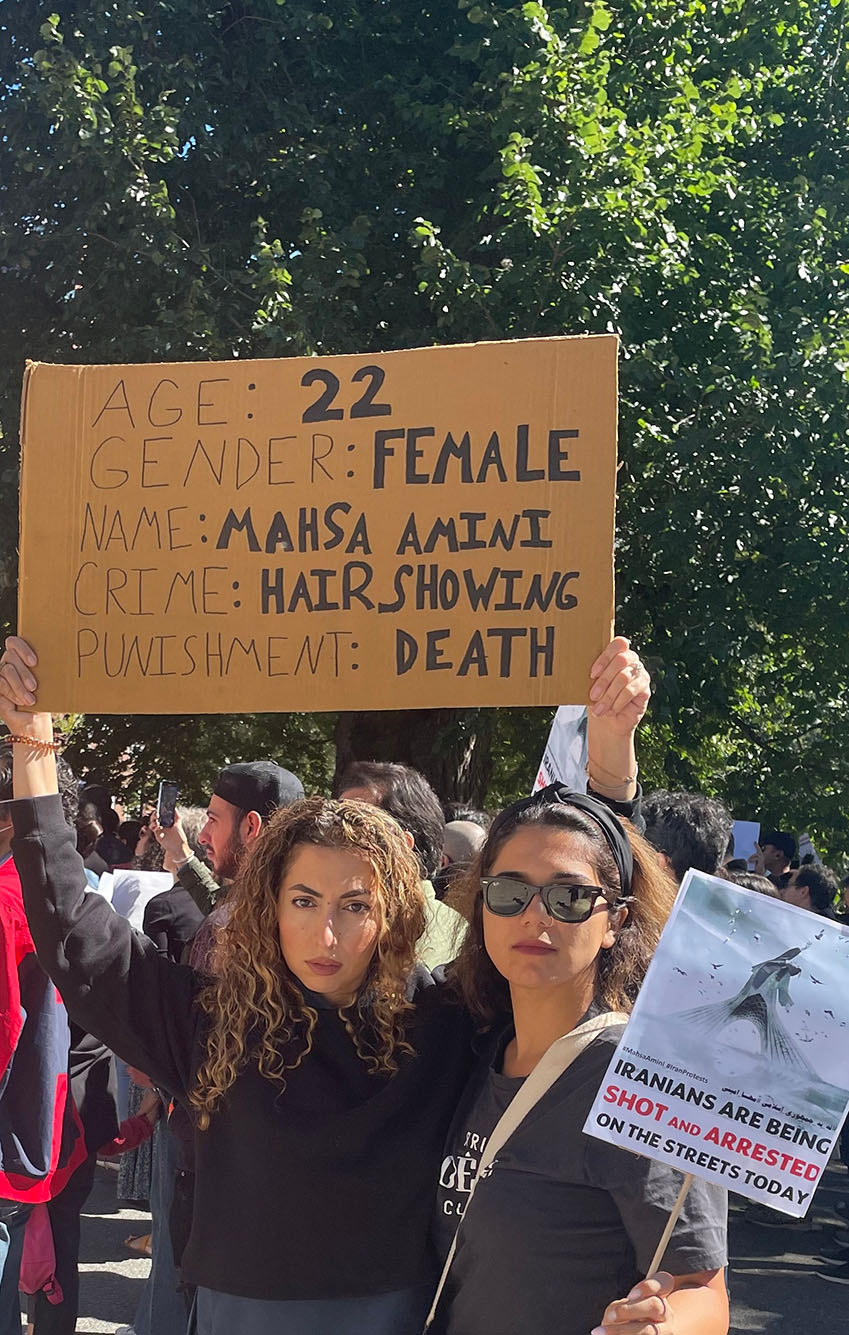

On September 17, mass protests erupted across Iran in response to the killing of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in Tehran while in the custody of Iran’s “morality police.” Amini was arrested for allegedly wearing her hijab—a mandatory head covering for Iranian women—too loosely. Photo by Ozan Guzelce/Sipa via AP Images

Anger, Pride, Fear: BU’s Iranian Students React to Mahsa Amini’s Death

“This is not what the Middle East deserves” and “This is a revolution,” students say, responding to the killing of a young Iranian woman over her hijab

“This is not what the Middle East deserves.”

“As long as there’s momentum here, there’s momentum there.”

“This is a very old wound.”

For Iranian and Iranian-American students at Boston University, the hours and days following the events of September 17 have felt like “heartbreak,” a “roller-coaster of emotions,” and the start of “a revolution of young people.” It could also mark the beginning of the first feminist revolution in Middle East history, one student says.

That was the day mass protests broke out in Iran over the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in Tehran while in custody of Iran’s so-named “morality police,” a government police force tasked with enforcing the country’s Islamic public dress code.

Amini was arrested for allegedly wearing her hijab—a headscarf worn by Muslim women and required in Iran for women when they’re out in public—too loosely, so that some of her hair showed. The reaction to her death, which Iranian officials have claimed was the result of a heart attack, was swift—and furious. Massive protests erupted all over the country. Multiple deaths and mass arrests of protesters followed. The current casualty estimate is anywhere from the 40s to the 70s, depending on the source, with that number including both protesters and police officers killed in clashes with citizens.

But it’s hard to know exactly what the number is—as well as what precisely is happening at any given time. Since the protests began, the Iranian government has shuttered social media and internet access across the country. Many Iranians currently have little or no ability to communicate with the outside world. In some places, internet access is limited to a few hours a day.

For Iranian students at BU, being in the dark while the chaos unfolds in their homeland is terrifying. Many haven’t heard from their family or friends since the protests began. (Note: Students who spoke to BU Today asked to be identified by initials only to protect family members still in Iran.)

The internet blackouts are an attempt to prevent reports of violence from leaving the country, says H.G., a second-year dental student who left Iran to raise his young daughter in Boston. After Amini’s death, the government “took the worst path of action,” he says.

“They could have just come clean and said, ‘This happened, we are sorry, and somebody has resigned over it.’ But they didn’t, and the truth came out. People took to the streets, and the government managed it worse than ever: they started killing people who don’t want anything extraordinary—they just want the freedom to wear what they want.”

Violence and censorship are regular tools in Iran’s government arsenal, H.G. adds, recalling a protest he participated in a few years prior where a mother and her two children were pulled into the fray. The police “broke every bit of glass on this family’s car—and they were just innocent passersby driving on the other side of the street,” he says. “But because this regime wants to induce fear and terror, they do these kinds of things to innocent people. It’s devastating and harsh.”

This is far from the first series of protests in recent history, says P.M., a graduate student earning a master’s in public health. (In 2009, Iranians protested over what was widely considered a rigged presidential election, and they protested again in 2019 against sudden fuel price increases. Both protests saw massive crackdowns from police forces.) But this is the first widespread protest over “human dignity” and civil rights, P.M. explains.

“The Iranian people’s hearts were broken [by Amini’s death]. She was only 22 years old and she didn’t deserve to be treated like that. What happened to that poor girl just started the fire again—it could have happened to me, one of my friends, my sisters, or anyone, because the morality police [have detained and mistreated many girls], but they’re lucky none of them died.

“Women do not have basic human rights in my country,” she continues, from the freedom of dress to their choice of profession. “This movement is all to show that people in Iran don’t want this government—and the government is killing them” in response.

These latest protests feel like a tipping point, the students say. Many of the citizens protesting are young, notes S.N., a former architect earning a master’s in painting at the College of Fine Arts. “This is a revolution of young people,” he says.

“My friends are all in the streets; people as young as 15 and 16 are in the streets. They’re standing in front of armed forces, facing bullets being shot at them.” He worries for his friends’ safety, he says, and his own for speaking out against the regime. But, “if they’re not scared, then I’m not scared,” he says. “I’m angry, I’m fraught, but I’m hopeful.

“I feel proud of the community that I belong to because I see how brave they are, fighting for their rights.”

What’s more, S.N. says, this could be the first feminist revolution in the history of the Middle East. Since the demonstrations began, women have been removing their hijabs and burning them in the street; some have even cut their hair in protest. (S.N. cut his own hair in solidarity.) And not only are women leading the movement, but the protests are uniting factions across the country in ways previously unseen.

“I think it’s time for people all around the world to pay attention to what’s going on in Iran right now,” he says. When it comes to the Middle East, “the head of the dragon is in Iran. If you cut the head off the dragon, the rest of the problems will be solved in the whole Middle East. I believe that if we win this fight against the regime, it’s going to mean a more peaceful Middle East and a more peaceful world for all people.”

All those BU Today spoke with cite frustrations with the dearth of media coverage around the protests. The internet blackouts are partially to blame. But there’s also a Western perception that this is business as usual, they say.

While P.M. was attending a protest for Amini in Boston, a woman approached her to ask what the protest was for. When she explained that a young woman was killed for violating Iran’s compulsory hijab policy, she says, the woman asked, “Isn’t that what’s always happening there? Why are you complaining about that?”

“In the early days of the protests, I was watching [American news], and they spent like, 30 seconds on this matter before going, okay, we have more important news to share with you,” P.M. says, comparing it with nonstop media coverage of the war in Ukraine. “It was so inappropriate that they thought the Middle East deserved to be treated like that.”

As Iranians in America, the students feel it’s their duty to speak up and speak out against Iran’s government. “I should be scared that by talking to BU Today and going to protests in Boston, [the government] will go and take my family. But I don’t care [anymore],” P.M. says. “I want people to understand what’s happening.”

The same goes for Iranian-Americans at BU. “My role is to let people know what’s happening in Iran and to urge government officials to take action,” says Iranian Students Association member H.S. (CGS’23), an Iranian-American who grew up in Dallas, but has spent summers with family in Iran.

“That means writing letters to local representatives, posting about it on social media. I’m doing anything I can because as long as there’s momentum here, there’s momentum there. The more people know, the more power this story holds.”

It’s important for Americans to also advocate for Iran, she adds. Contacting representatives, donating to fundraisers for Iran, raising awareness online—all could help prompt the government or United Nations interference the country desperately needs, H.S. says.

It’s difficult to say what will come of the protests. A regime change, an end to compulsory hijab, restoring rights to women, even sanctions against Iran—everything is up in the air without international pressure, S.N. says.

“There is no way to communicate with this regime,” he says. “I think that’s the thing all the Western governments should know. Because now it’s time to decide: are you going to be on the side of the Iranian people, or are you going to be on the side of Iran’s regime?”

The Iranian Students Association is hosting a candlelight vigil on Marsh Plaza for Mahsa Amini on Thursday, September 29, at 7:45 pm.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.