How China’s Box Office Shapes the Movies Americans See

Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014) may be just a silly action movie, but the Chinese government exercised its box-office clout to be sure the film depicted China in a favorable light, writes Erich Schwartzel (COM’09) in his new book. Credit: Paramount Pictures

How China’s Box Office Shapes the Movies Americans See

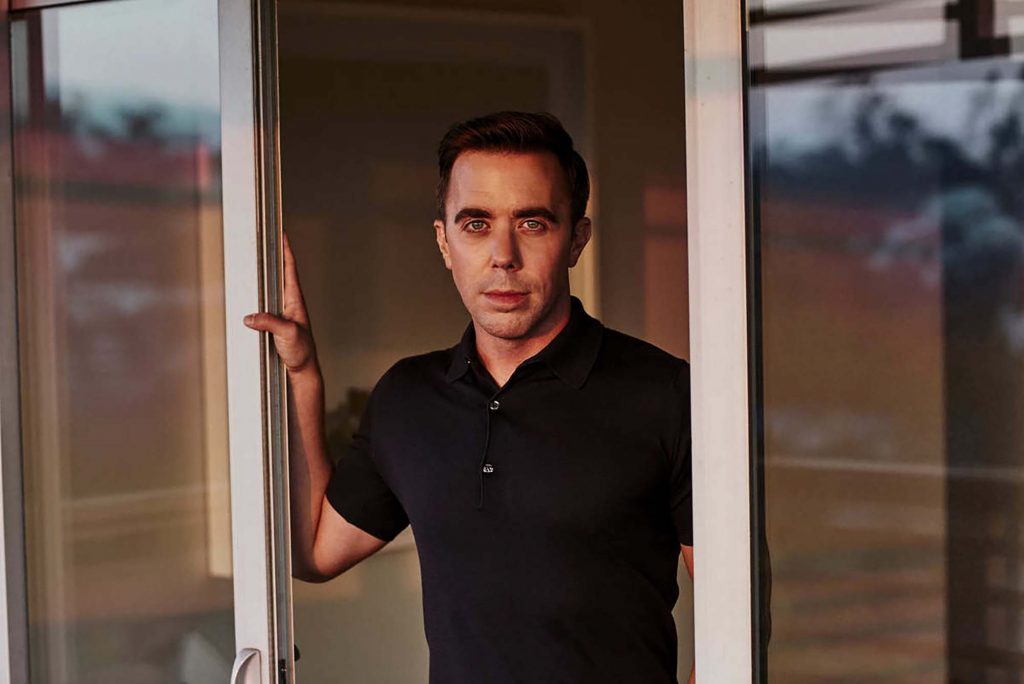

Erich Schwartzel (COM’09) documents a controversial relationship worth billions to Hollywood in his new book, Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy

The 1984 hit movie Red Dawn depicts a bunch of Colorado high schoolers fighting a Soviet invasion of the United States. When MGM shot a remake in 2010 for a new generation of moviegoers, the communist invader was changed to China.

Until Chinese officials saw promotional photos from the set, that is.

“Before long, the studio had a sequel of the worst kind on its hands,” writes Wall Street Journal reporter Erich Schwartzel (COM’09) in his new book, Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy (Penguin Press, 2022).

Hollywood had angered China years earlier by making films about Tibet and the thriller Red Corner, an unflattering depiction of the country’s internal security and justice systems. Chinese officials were not about to allow their nation to be seen in an unflattering light again. And with the collapse of the DVD market, Hollywood needed to hold onto the lucrative Chinese box office.

MGM decided to change the invaders to North Korean, even though the movie had already been shot.

Custom Film Effects in Burbank, Calif., was used to jobs like erasing an errant boom mike from a shot or digitally clearing up an actor’s complexion, always done under strict confidentiality. They faced an enormous task with the new Red Dawn.

“Chinese flags appeared throughout the movie on trucks and on the arms of soldiers’ uniforms,” Schwartzel writes. “Chinese banners hung off the sides of buildings and Chinese propaganda posters were displayed on nearly every outside wall. Even the epaulets on the soldiers’ uniforms had to be changed, since they were Chinese military medals and not North Korean ones.”

The effort took two months and cost a million dollars. MGM also had to redo an opening montage, and many lines of dialogue had to be rerecorded. Never mind that a North Korean invasion made even less sense than the original story.

The movie was sold off to a small distributor that did no business in China. Released in 2012, it did a so-so $45 million at the US box office. But Hollywood’s access to millions of Chinese moviegoers and billions of dollars in tickets was preserved.

“The aha moment for me was realizing what a political story this was, beyond just an economic or cultural one,” Schwartzel says.

Other journalists have written about the Hollywood-China relationship, especially since 2015, when there was a surge of Chinese investment in Hollywood, “but I didn’t feel like anyone else was putting it in the geopolitical context that every other story about China was in,” he says. When Donald Trump won the presidency the next year, the ideological differences really came into focus. Hollywood became a “proxy battleground.”

“The movies have always been these ‘hearts and minds’ factories that have played a huge role in selling America to the world,” Schwartzel says. “And here was this country that was setting itself up as our ideological alternative,” but also had a hand on the controls of that dream factory.

Other world powers have tried to steer Hollywood, of course; in the 1930s, even the Nazis expected studios to acquiesce to their demands and threw them out of the lucrative German market when they wouldn’t. But China’s influence today has an unprecedented depth and breadth, thanks to the country’s many millions in investments and its box-office clout.

“Anytime a foreign entity has had influence in Hollywood, if it’s financial, it’s usually perceived as dumb money that comes and goes,” Schwartzel says. “If it’s a censorship relationship, it usually only goes one way. If Indonesia or Saudi Arabia want to censor a movie, they censor it for Indonesian or Saudi audiences. But the Chinese have an economic leverage that allows them to censor movies shown anywhere around the world.”

Some of the changes are silly and harmless. Chinese stars started turning up in Marvel movies like Iron Man 3. And then there were those China Construction Bank ATMs inexplicably scattered across Texas in Transformers: Age of Extinction. But as with Red Dawn, sometimes the changes are more substantial, even going directly to geopolitical concerns.

“I thought that a case study of a chapter on Transformers would be an amusing detour. I thought it would be funny, all the illogical choices they made with the product placement and the casting,” Schwartzel says. “And then when I watched the movie again, I saw this scene where Hong Kong is being destroyed by the giant robots, and we’re in the middle of this climactic battle scene, and there’s a cut to Beijing where the defense minister is informed of the situation and says, ‘The Central Government will protect Hong Kong at all costs.’ And I thought, what a weird thing. I asked the execs who worked on the film about it. And they said, ‘Oh yeah, when we went to China to get approval for all this, the authorities read the script and they had one request—can China come to the rescue of Hong Kong first?'”

The script was rewritten. And Chinese jets got there first to protect Hong Kong.

“I was writing this section as the pro-democracy demonstrations were filling the streets of Hong Kong every night,” Schwartzel says. “I tracked down this assistant director who worked on the film, who was from Hong Kong, and she says, ‘This is it, they’re starting, they’re trying to merge the province with the mainland, even in this Hollywood blockbuster that no one is watching for geopolitical messaging.’ It was an example of how this story is this very surreal blend of hilarious and disturbing.”

The Chinese have an economic leverage that allows them to censor movies shown anywhere around the world.

Meanwhile, Transformers: Age of Extinction pulled down a then-record $301 million at the Chinese box office. “Most important for those officials in the Forbidden City,” Schwartzel writes, “the movie’s global haul of $1.1 billion meant that millions of moviegoers around the world watched Beijing’s heroism.”

He says that “it quickly becomes a question of values. A lot of values that American audiences have almost universally agreed to be distinctly American values do not comport with the values of Chinese censors. Those values can get corrupted. And I think that makes a lot of Americans quite queasy.

“The other thing people should care about is the stories not being told, the movies, topics, and themes that are just completely off the table, the self-censoring that happens within American borders with no direct coercion from Beijing.”

Over the past few decades, Hollywood films have not explored China in any complexity. There haven’t been any more major films about Tibet, for instance—or the real situation in Hong Kong, when no Transformers are involved. Schwartzel says that China’s rise on the world stage has not really been interrogated by the most powerful medium in the world.

“That’s not to say Hollywood should be making a lot of movies that demonize China,” he adds, “but if we agree that the tension between the West and China is going to define this next century, then usually the movies would do some exploring of that—and because of the economic stranglehold that China has on Hollywood, they can’t.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.