Addressing the Ethical Issues at the Heart of the COVID-19 Pandemic

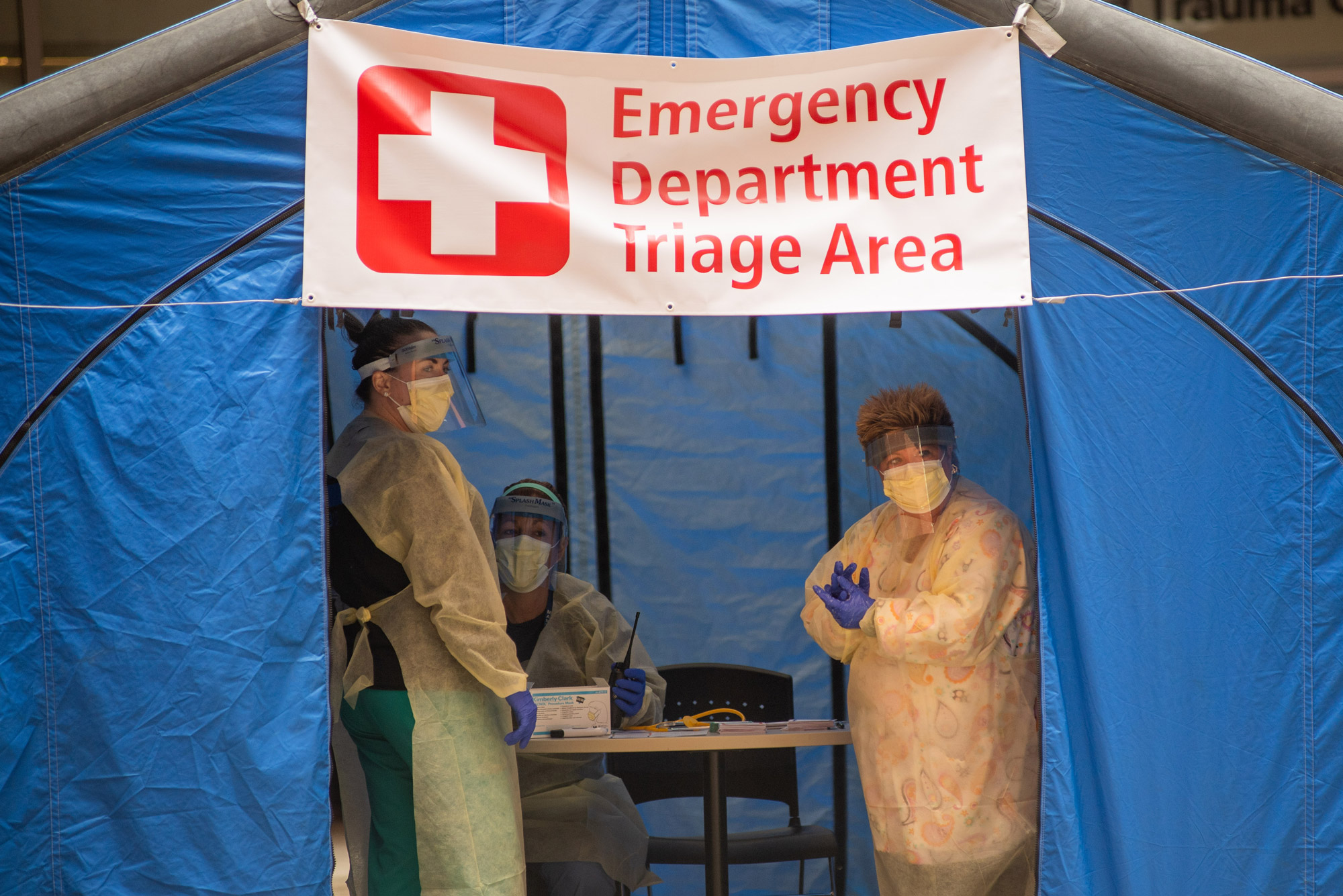

Nurses awaiting patients outside Boston Medical Center during the early days of the pandemic, March 20, 2020. The staff in the triage tent assessed patients’ symptoms and determined whether they could receive care through BMC’s influenza-like illness clinic (ILI) for more moderate symptoms, or if they needed to go to the Emergency Department for more serious conditions.

Addressing the Ethical Issues at the Heart of the COVID-19 Pandemic

At annual Alan and Sybil Edelstein Professionalism and Ethics in Medicine Lecture, Boston Medical Center experts discuss some of the ethical care challenges they faced during the pandemic

A panel of experts from Boston Medical Center (BMC), BU’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine teaching hospital and Boston’s safety net hospital, gathered recently to reflect on many of the ethical issues doctors were forced to confront during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The occasion was the second annual Alan and Sybil Edelstein Professionalism and Ethics in Medicine Lecture, held virtually November 30. The event was sponsored and moderated by David Edelstein (CAMED’80), a member of the school’s Dean’s Advisory Board and Northwell/Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital director of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery.

“As we thought about topics for this year’s lecture, what stood out was how the COVID crisis intensified the challenges of doctor-patient ethics, particularly in areas such as autonomy, equity, privacy and trust,” said Marcia Edelstein Herrmann (CAMED’78), in introducing the lecture.

At the height of the pandemic, David Edelstein served for two years as interim chair of otolaryngology at New York City’s Northwell/Lenox Hill Hospital, a period he called the most challenging time of his career.

“Nothing quite challenged us like the COVID crisis,” Edelstein said, and during a crisis, physicians and healthcare workers cannot just rely on their moral compass. “Ethical care changes in that the solidarity is with the group. It’s with not just one patient, but all your patients…in many patients and the patients you’re not treating.”

On the panel of experts were Ravin Davidoff, a BU professor of medicine and BMC executive medical director; Michael Ieong, a BU assistant professor of medicine and BMC medical intensive care unit medical director; Jessica Pisegna (Sargent’16), a BU assistant professor of otolaryngology and BMC speech and language pathology section chief; David Hamer, a BU professor of medicine, a School of Public Health professor of global health, and a BMC infectious diseases attending physician; and Jacob Bloom, a BMC fourth-year otolaryngology–head and neck surgery resident.

The COVID-positive patient census at BMC skyrocketed from 22 patients on March 24, 2020, to 121 patients in just eight days, and reached 219 by April 9. It marked a shift in focus from the individual to the overall public good and “maximizing survival at the community and societal level,” said Davidoff. At that time, central state coordination had not yet been established.

“We knew there were going to be bed shortages,” Ieong said, but “the overall system was very slow to respond and plan for that.”

Scarcity of medical and personal protection supplies, no vaccines or proven medications, and an inadequate system of testing exposed the social inequities in healthcare, said Davidoff, with Blacks and Hispanic/Latinx accounting for 76 percent of BMC’s inpatient admissions, double the number of inpatient admissions of people who were homeless compared to the previous year, and Blacks accounting for nearly half of COVID deaths at BMC.

Rationing of supplies, medicines, and medical equipment seemed inevitable, and hospital leaders and staff determined decisions would be made with the guiding principles of equity, accountability, and transparency. For example, to address a critical ventilator shortage, the hospital formed a response team that would take the decision-making on who would get a ventilator out of the hands of the primary care teams.

“We had a plan in place and thank God—thank God—we never had to deliver on that approach,” Davidoff said during the event.

Ieong noted that the medical teams felt there was a fundamental obligation to provide care for all people. “Fairness was a big issue,” he said, and communication was the key to transparency and accountability.

When vaccines became available, Davidoff said, the team had to decide which healthcare workers were prioritized. “We very publicly talked about how we were making the decisions about which employees would be in the first wave…and how we would roll that out,” he said.

Early on, BMC started training additional personnel of all specialties to deliver intensive care unit–level care. Bloom, a new intern when he was asked to help in the ICU, said he “thought if there was ever a time to stand in there and help out, not just the patients in front of me, but society as a whole, this was my time to contribute.”

Pisegna’s specialty, speech therapy, came with high risk. Her teams worked up close with COVID patients who had trouble speaking or swallowing or who had throat surgery and tracheotomies. They had to triage patients based on the severity of their malady, with more severe cases seen in person and others remotely. When the hospital needed beds, Pisegna said, a patient who needed only a swallow test to be discharged was prioritized.

A crowdsourcing approach helped BMC survive, Hamer said. They’d bulk-buy drugs they thought they’d need, and clinicians were on call 24 hours a day to consult with infectious diseases specialists on the wards about who should receive the limited amounts of certain drugs to help slow the COVID-19 progression. “There’s some really challenging ethical decision-making in this process,” he said. They developed a protocol for identifying patients who were most likely to benefit.

“It took a lot of effort to make sure the right patients received treatment,” Hamer said. “They did a great job.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.