A Bold New Plan to Reduce the University’s Waste

New waste bins in student residences are part of the Zero Waste Plan. Photo by Kaity Robbins

A Bold New Plan to Reduce the University’s Waste

Task force recommendations aim at mitigating climate change and building a more equitable society

By the end of this decade, life for BU students, staff, and faculty will have changed in many small ways, from how they buy furniture to the way they throw out candy wrappers. Those small changes, all part of BU’s new Zero Waste Plan, will add up to one enormous difference in the impact that the University has on the environment and on human health.

The plan, which was presented Wednesday at the Spring 2021 Management Town Hall Meeting by Dennis Carlberg, associate vice president for sustainability, is the product of more than four months of analysis and discussion by a 54-person task force, led by Carlberg and Paul Riel, associate vice president for auxiliary services, and including representatives from Campus Planning & Operations, Auxiliary Services, Sourcing & Procurement, Information Services & Technology, Environmental Health & Safety, Events & Conferences, and Sustainability, as well as faculty and students. It calls on the BU community to 1) reimagine the very notion of waste, and 2) to eliminate wasteful practices throughout the life cycle of materials—meaning from purchase to discard.

The plan’s measurable goal is as ambitious as its scope: it hopes to enable BU to attain an industry metric known as Zero Waste by 2030. And while Zero Waste is not quite as challenging as it sounds—it requires diverting at least 90 percent of an organization’s nonhazardous waste from the traditional routes like landfill or incineration to some form of reuse or recycling—Carlberg acknowledges that it’s a challenging target.

“Zero Waste will not be easy to reach,” he says. “But Zero Waste is definitely attainable. For BU, getting there starts with prioritizing strategies. We have to think about how all of our processes can be more efficient, and then we have to redesign them accordingly.”

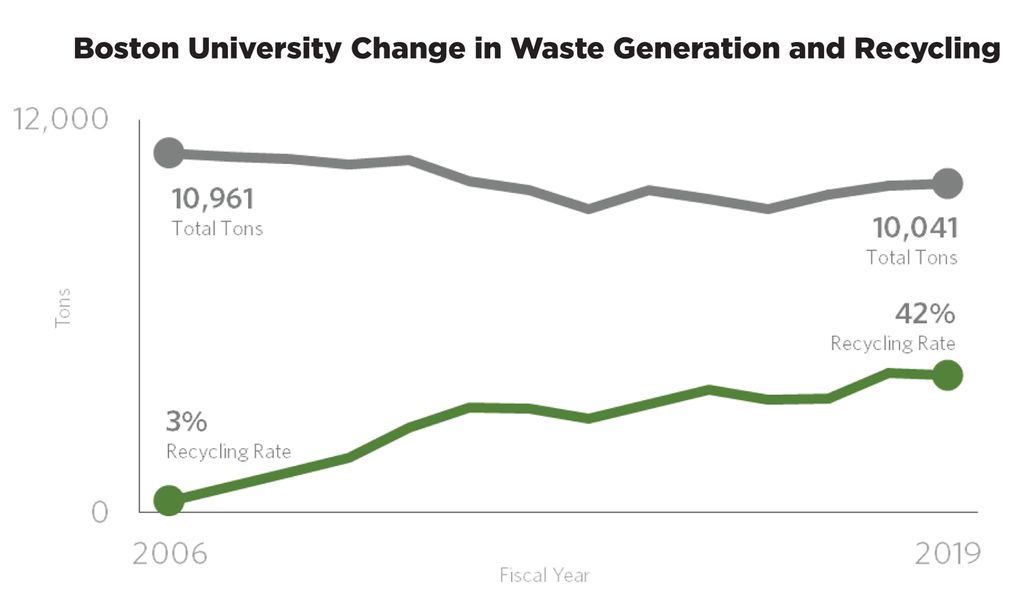

In fact, the University has been redesigning its processes for several years, and the result is impressive. In 2006, the diversion rate of BU’s nonhazardous waste was a paltry 3 percent. By 2019, it had climbed to 42 percent, meaning that almost half of BU’s waste was not contributing to the generation of greenhouse gases, such as methane (from landfills) or CO2 (from incinerators). And during that same period, the University reduced its overall generation of waste materials by 8 percent, from 10,961 tons to 10,041 tons, excluding construction waste.

“That’s very good progress,” says Carlberg. “We should all be proud of that, but we know that we can do better. To accelerate the speed of our progress in the next 10 years, we need the entire BU community to participate in transforming the system by taking action to reduce their individual impact and participating in the operational changes that are underway.”

Much of that redesigning is described in Zero Waste protocols that have been developed by the Zero Waste International Alliance, Zero Waste USA, Green Business Certification Inc., and Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives over the past two decades and have been put into practice at many corporations, among them General Motors, Walmart, and Sierra Nevada, as well as municipalities, including Boston, which adopted a Zero Waste plan two years ago.

The University’s plan, which includes many of the standardized practices, was first envisioned three years ago as part of BU’s 2017 comprehensive Climate Action Plan, with a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. BU’s waste stream contributes 8 to 10 percent of the University’s greenhouse gases, so reducing the volume of waste will help reduce BU’s contribution to climate change. Similarly, reusing materials should eliminate harmful emissions associated with the manufacturing processes for new materials. “Recycling an aluminum can,” Carlberg points out, “requires much less energy than mining and smelting the ore.”

In fact, the issues that the Zero Waste plan hopes to address extend beyond climate change. “It comes down to human health and equity,” says Carlberg. “Our discards, especially plastics that pollute the environment adversely, affect human health, and they affect it disproportionately for communities of color. We need to eliminate the whole concept of waste and think of the end product of one system as the resource for another system. We need to think about this as a cradle-to-cradle system that supports a circular economy. Remanufactured or repurposed furniture is an example of how a circular economy works. This goes well beyond BU. The more we can support a circular economy, the more successful it will be—and we will be.”

Like neighborhood swap websites

The Zero Waste Task Force met regularly to develop recommendations during fall 2019 and completed the final draft of their plan last March. They were preparing to present the plan to University leadership when COVID-19 brought everything to a halt.

“We are now reengaging everyone and moving toward implementation of the initiatives they developed,” says Kaity Robbins, BU Sustainability Zero Waste manager and a leader of the task force. “This is a very exciting time.”

Operationally, Robbins says, the task force has recommended dozens of changes and wrapped them up in 21 key initiatives. “We are incorporating Zero Waste guidelines into the way we approach building new spaces and renovating existing spaces,” she says. “We’re moving toward remanufactured furniture instead of buying new. There are also going to be some very visible changes across campus in terms of our collection infrastructure, like the waste bins in buildings.”

Finding ways to cut waste out of the University’s supply chain is an important first step. Robbins says Sourcing & Procurement will work with suppliers to help meet recommended sustainability standards. To help reduce BU’s carbon footprint, for example, vendors will be asked to minimize the number of times their delivery trucks visit campus. And to reduce the energy and resources invested in equipment and furnishings, faculty and staff will be encouraged to consult a community-wide surplus exchange not unlike neighborhood swap websites. To be sure that waste reduction is fully integrated into life at BU, the plan recommends spelling out expectations of employees’ commitment to Zero Waste in job descriptions and documenting supporting actions in performance evaluations.

Recycling an aluminum can requires much less energy than mining and smelting the ore.

Robbins and Carlberg expect to see many of the practical changes adopted more readily than what they consider a fundamental and required transition to a mindset that sees waste as a resource. “To lay the foundation for that change,” says Carlberg, “we need a simple and robust resource [waste] collection system, and we need data sharing so people can see the results of their actions. That will support the shift in our culture, which will be necessary for us to reach our Zero Waste goal. And that is going to require the participation of everyone. We all need to be part of the solution.”

Carlberg’s confidence in the plan stems largely from the depth of institutional knowledge that stakeholders brought to the table. “We had people on the task force from many different departments across BU,” he says, “and we also had excellent leadership from the top, particularly from President Brown. All of us worked together and developed this from the bottom up. It was shaped by people who really understand how the University works.”

While he acknowledges that the 2030 goal of 90 percent diversion will be challenging, Carlberg believes the plan’s recommended actions can divert an additional 2,800 tons per year from landfills and incinerators, enough to increase the University’s diversion rate from its current 42 percent to 70 percent. And when new efforts to minimize waste from construction debris are factored in, the potential diversion rate will jump to 84 percent.

The Zero Waste Plan will also save money. “Waste is an indicator of inefficiency,” Carlberg says. “Boston University now spends over $1.5 million on waste disposal each year, and while many of our Zero Waste initiatives will come at a cost, they will have significant triple bottom line benefits. They will reduce costs through avoided collection and disposal fees, and that savings can be used to offset the cost of other measures that may not have a financial payback.”

In addition to exploiting the task force’s inherent expertise, members solicited advice from Zero Waste Associates, a California-based consultancy that helped design the city of Boston’s Zero Waste Plan and has worked with several colleges and universities. Gary Liss, a principal of the firm, says BU’s plan stands out because of its focus on gathering more reliable data and making data-driven decisions. “It’s an ambitious plan,” says Liss, “at least compared to plans of other universities. Very few universities are farther ahead in terms of planning and goals.”

And yes, Liss says, BU’s goals are achievable. Definitely.

The Zero Waste Task Force asks the BU community to read the Zero Waste Plan and think about how you can help implement it in your department and/or daily life. Feedback can be provided in the Comment section below or via email to sustainability@bu.edu through April 5.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.