Undercover with Homegrown Terrorists

COM Prof Dick Lehr’s White Hot Hate tells the story of an unlikely hero in Kansas

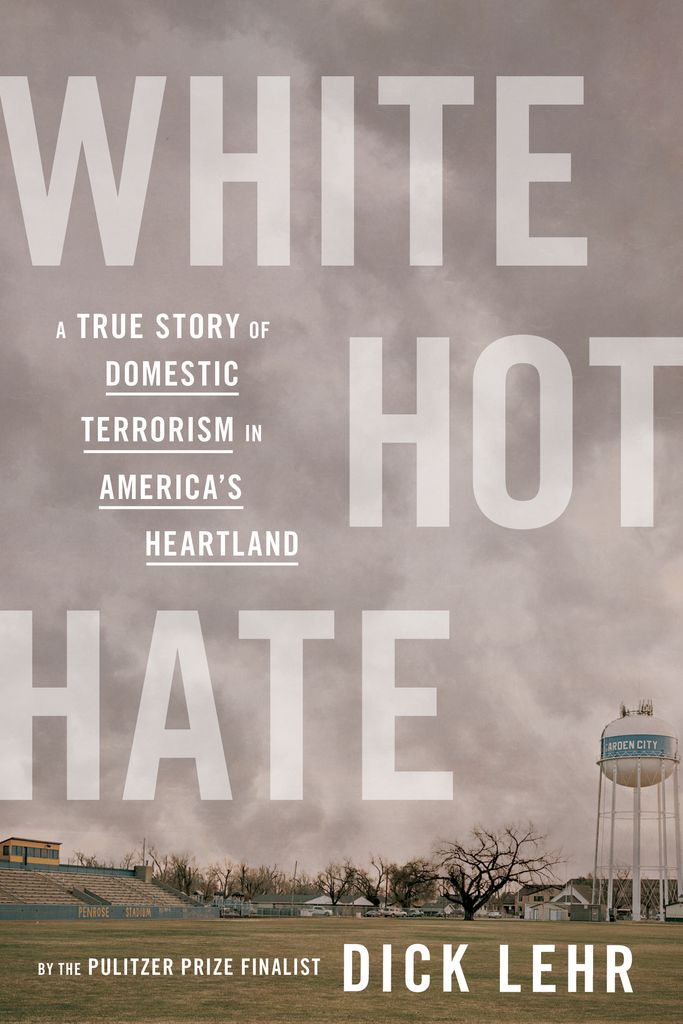

Dick Lehr, a COM journalism professor, has a new book out, White Hot Hate, examining a case of domestic terrorism and the improbable informant who stopped the plot. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Undercover with Homegrown Terrorists

COM Prof Dick Lehr’s White Hot Hate tells the story of an unlikely hero in Kansas

In a Boston suburb one afternoon in spring 2019, a neighbor knocked on Dick Lehr’s door and said he had some guests that Lehr ought to meet. The neighbor knew that Lehr was a former Boston Globe reporter who had worked on the paper’s investigative Spotlight Team and had published several true crime books. And his guests had a hell of a story to tell.

“Yeah, I think he was thinking: book,” chuckles Lehr, a College of Communication professor of journalism. “I’m just glad I was home!”

The three guests were returning home to tiny Garden City, Kans., from a panel on reconciliation at Dartmouth: Mursal Nayele, who was something of a leader in his Somali immigrant community; a hospital executive named Benjamin Anderson, who was trying to make the Somalis feel welcome (and was an old friend of Lehr’s neighbor); and an average-looking blue-collar guy named Dan Day.

Average-looking or not, Day had worked undercover for the FBI to stop homegrown terrorists who planned to blow up a Garden City apartment complex that many Somalis called home.

Lehr was captivated by their story, which he tells in his new book White Hot Hate (HMH Books, 2021), his eighth nonfiction book, subtitled A True Story of Domestic Terrorism in America’s Heartland. He will read from the book at Brookline Booksmith on Wednesday, December 1, at 6 pm (details below).

That afternoon, he “went over and spent about an hour with them and right away the story wheels started turning,” says Lehr, whose previous books include Black Mass: Whitey Bulger, the FBI and a Devil’s Deal, which became a Johnny Depp movie.

“I was in recovery from my prior book [the World War II tale Dead Reckoning] and was not looking to write another one right away,” he says. “I had handed in the manuscript five or six weeks earlier, and I was exhausted. Part of me was like, aaargh, but once those wheels start turning I can’t stop them. I had just the vaguest memory of the story. So I came home, jumped on the computer, and started reading about it…”

It was, for many Americans outside of Kansas, a one-day story, just another tale of a thwarted attack.

The June 2016 mass shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando by a Muslim pledging fealty to ISIS had enraged members of a Kansas militia splinter group who called themselves Crusaders. Their hatred for Muslims had been building as the Somali community grew in Garden City; now they decided to detonate bombs to slaughter people they believed were working for a jihadi takeover of the United States.

The militia had been trying to recruit Day, a conservative and a gun owner, who was not fond of Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, or big government. But the more angry his new friends became, the less comfortable Day grew. He remembered the horror that another homegrown terrorist’s bomb had inflicted on Oklahoma City, in 1995, not that far away. And he agreed to become an undercover informant for the FBI, infiltrating their wannabe terror cell and ultimately heading off their plot.

The three plotters were arrested in October 2016 and convicted and sentenced to long prison terms a few months before Lehr’s neighbor knocked on his door. Day was now free to talk.

“Right away, I felt this not only has real book potential, but also, this is the kind of story I love to do,” Lehr says. “At the heart of it, you have this true-crime quality to it, with a lot of action and drama, which is always hard to resist. I love the timeliness of it, with the rise of militias and white nationalism and Islamophobia. All that stuff just made it feel urgent in a way.”

He set to work immediately. “There was that courtship period, because it ain’t goin’ to go without Dan Day’s cooperation and access, and that took a while,” Lehr says. “My agent got excited, and there was a book proposal to do, but in the meantime, I needed to get to know Dan and present what I wanted to do. He’s not used to the press. There was a wariness from what little contact he’d had with the press, and then there’s the wariness from he’d just never done anything like this before.”

Day’s ordinariness was part of what made the story extraordinary. He was diffident, private, devoted to his family, struggling with health and financial challenges. His politics and his economic struggles made him appear a likely recruit to the militia group, but he was also very much his own man, serious about right and wrong. And he was stalwart; as a teenager he had jumped into a river to help save drowning children, even though he didn’t know how to swim.

For eight months, this quiet man did his best to convince the hatemongers that he was one of them, sitting through long tirades aimed at Muslims and violent threats credible enough to worry the FBI. He wore a wire to meeting after meeting, sometimes with little or no backup nearby, and joined in as they practiced with semiautomatic weapons and planned an attack that horrified him.

Lehr built his account from trial transcripts and recordings of meetings and phone calls where the plotters appear both terrifyingly unhinged and buffoonish.

“It’s jaw-dropping, the depths of their hate,” says Lehr, who tried to obtain jailhouse interviews with the men, without success. “After the Pulse shootings they announced their determination to ‘exterminate the cockroaches,’ but getting there is hardly a straight line in any kind of competent, efficient way. They have a meeting for three or four hours, and there is an agenda, but they go off sideways on some tangent that has nothing to do with anything, like the best brand of some tool.

“Then, lo and behold, at the end of July they’d made a blasting cap. At the end of the day, they were capable of pulling it off. Not in any kind of very organized way, but they were getting there.”

No question that Day was risking his life—and more. Keeping secrets was difficult in the family’s modest home, and mostly unbeknownst to the FBI, his wife and teenaged son and daughter knew what he was doing.

It’s jaw-dropping, the depths of their hate.

Lehr intercuts Day’s story with the struggles of the local Somali community, who were welcomed by some, ostracized by many others. Anderson, the hospital executive, tried to involve the Somalis more in the community with the help of Nayele, whose store was an unofficial community center for them. At the same time, the militia kept the store under periodic surveillance, believing, for no particular reason, that it was a hub of ISIS terrorist activity.

In the end, the plotters were exposed by one of Kansas’ own. Day’s heroics, and the way the community came together afterward, provide an optimistic note.

“I hope so! That’s what drew me to the story,” Lehr says. “Here’s a story where the bombs didn’t go off. It doesn’t end in horror and tragedy. For once, I was able to write something deeply dramatic and intense and timely—‘This is America now’—but I like the fact that in the end, the bombs did not go off. Garden City was tested, it bent but didn’t break, and there’s this sense of, maybe, hope at the end.”

Footnote: While in Kansas, Lehr also made a connection to one of literature’s most famous true crime tales. Day and his teenage son invited Lehr to go target shooting with them on a remote Kansas property owned by a relative. As they were driving out there, they passed a morbid Kansas landmark, and Lehr asked to stop so he could take a picture. It was the Clutter Farm, the scene of the murders in Truman Capote’s groundbreaking In Cold Blood.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.