Lee McIntyre: How to Talk to a Science Denier

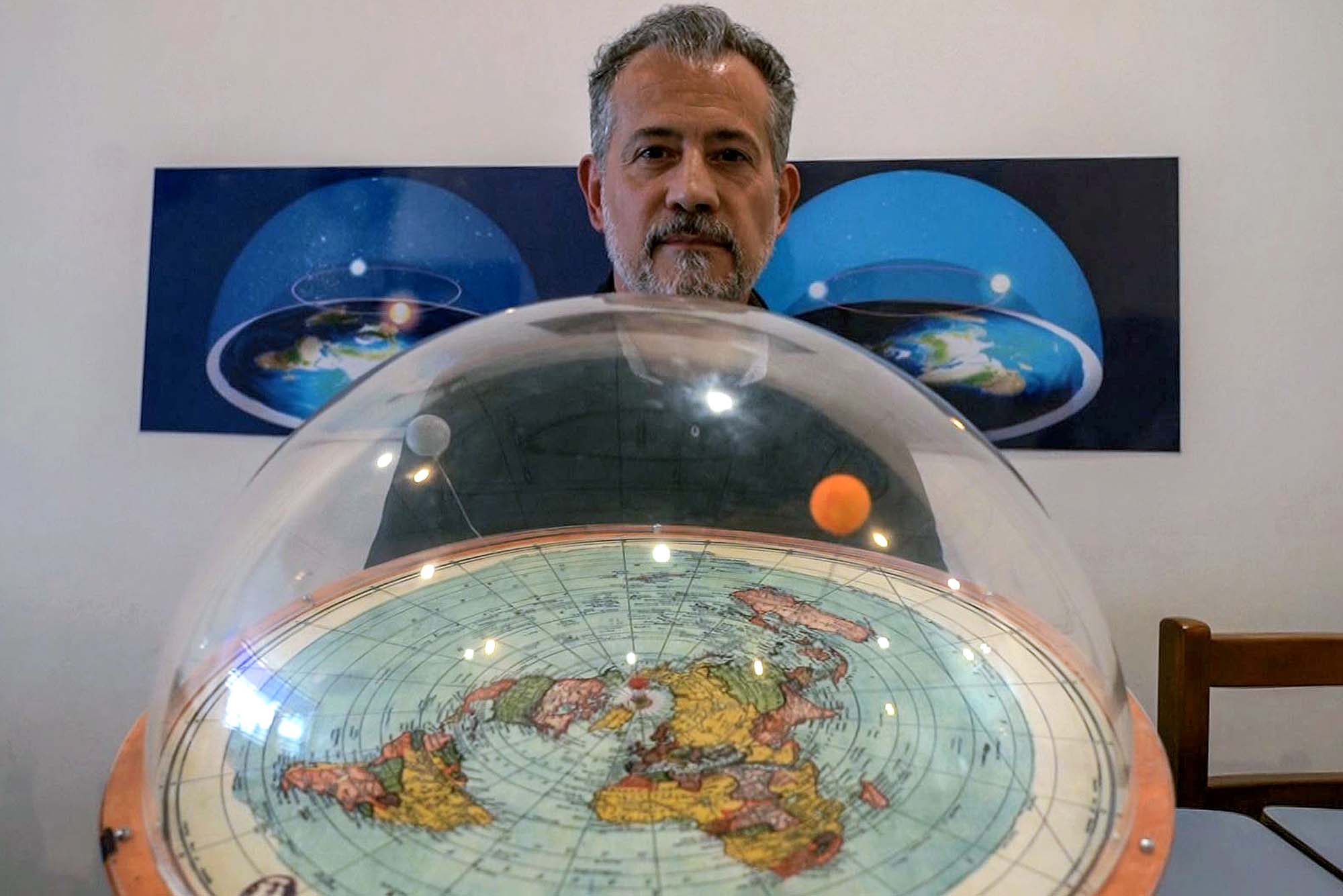

Brazilian flat-earth conspiracy theorist Anderson Neves displays a model of what he believes the planet really looks like, including a giant dome. Photo by Florence Goisnard/AFP via Getty Images

How to Talk to a Science Denier

In new book, BU’s Lee McIntyre says empathetic listening key for reasoning with flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, climate change deniers

Most field research doesn’t require “two days in an asylum.” That’s how Lee McIntyre describes the 2018 Flat Earth International Conference in Denver that opens his new book, How to Talk to a Science Denier (MIT Press, 2021). McIntyre, a visiting researcher at Boston University’s Center for Philosophy & History of Science, was seeking the best way to reason with science deniers, starting with “the worst of the worst” whom “even other science deniers would make fun of,” he writes.

The book roams beyond low-hanging, flat-earth fruit to ponder anti-vaxxers, climate change deniers, creationists, and the rare case involving otherwise progressive people: opponents of genetically modified organisms. (“There have been no credible studies that have shown any risk in consuming them,” McIntyre writes.) His book argues that with crises like climate change at a tipping point, weaning deniers from unreality is critical for our future.

BU Today spoke with McIntyre for tips on handling crazy Uncle Harry over the coming holiday dinner table.

BU Today: In a world beset with racism, inequality, authoritarianism, immigration crises, and COVID, how does science denial rate on the scale of problems?

McIntyre: If you scratch the surface, science denial is behind some of those issues. Think of where we are with climate change, with the pandemic. The reason we’re not making more progress on both is science denial—not just in the general population, but also in Congress. We live in a denialist culture, where people say things that they don’t have to be accountable for. Think of the “Stop the Steal” campaign, the January 6 insurrection. I cannot think of bigger threats to democracy. At their heart, those are denialist campaigns for which the blueprint is science denial.

There are five tropes of science denial reasoning. Those five were used in the Republican pushback against the Mueller report, in “Stop the Steal,” and the pushback about the January 6 insurrection: cherry-picking evidence, belief in conspiracy theories, illogical reasoning, reliance on fake experts, and belief that if your opponent isn’t perfect, then you’re right. That is the strategy used by COVID deniers or evolution deniers. There’s a good case that that’s the reasoning used by today’s Republican party.

BU Today: What percentage of responsibility do you assign religion for anti-science beliefs?

McIntyre: There isn’t any polling data. There’s no way to know. About 70 percent of flat-earthers are evangelical Christians, but most evangelical Christians are not flat-earthers. Flat-earthers that I met complained of getting kicked out of churches for their flat-earth beliefs. I did have one guy say that flat earth was the only thing that made it possible for Noah’s flood to happen, [as water would] fall off [a spherical Earth]. No! Because water is subject to gravitational pull, it could be a planet of complete water and still be [spherical]. Evolution denial is almost completely based on evangelical Christianity. Other than that, there are different motivations—religious, economic, political—for different types of science denial.

BU Today: Is science denial easier and more prevalent in our online, depersonalized world?

McIntyre: I do think that there is more science denial now than there used to be, and what I would chalk that up to is the internet. When I was a kid, there was the guy on the street corner handing out mimeographed sheets with conspiracy theories. Now you can get a website, and there are a hundred thousand followers. I see the internet as the accelerant for disinformation.

Human beings have cognitive bias built into us. But bias is only a piece of the story. For science denial to be rampant, we have to start pruning our friends and information sources according to whether they believe what we believe. Then we’re not getting pushback from anybody who disagrees with us, and in a time of political polarization, we’re seeing people on the other side as our enemy.

This is not the worst time in history for science. Think back to Galileo’s era; they burned Giordano Bruno [a friar who argued planets revolved around suns] at the stake. But is science denial worse today than 30 years ago? I think it is. Social media have allowed disinformation creators to spread their lies. There was a story on NPR that 65 percent of the anti-vax propaganda on Twitter comes from 12 people.

BU Today: How do you talk to a science denier? And will it actually work?

McIntyre: Science denial is not just about doubt, it’s about distrust. The way you overcome distrust is not through sharing accurate information, it’s through conversation, face to face, in which you’re calm and patient and show respect and listen. Having the right attitude is the only thing that gives hope of success.

That’s not to say that it usually works, because by the time somebody goes down this rabbit hole, they can be too far gone to reach. I think of it like a soccer field: by the time it gets to the goalie, it’s gotten through all those other people. When you’re questioning belief, you’re questioning their identity, and that’s a heavy lift.

It has been done. Jim Bridenstine, [former] member of Congress (R-Okla.), gave a speech on the floor of the House in which he said the things that climate deniers say. Of course, that meant Trump appointed him head of NASA. Bridenstine was head of NASA only a month or two, and he changed his mind. That happened because he met those scientists—the “Other,” the evil ones he didn’t trust—and he came to learn they were reliable, honest people. He began to trust them, and that’s what led him to change his mind.

BU Today: What do you say to those who might respond, “I don’t have time or responsibility to go down endless rabbit holes with science deniers?”

McIntyre: A study in 2019 took that five-trope strategy and showed—it’s called “technique rebuttal”—that that was effective for laypeople to talk science deniers out of their wrong beliefs. So, don’t tell me that it’s not possible. If people say, “I don’t have the time,” there’s nothing I can say. But if they say, “That’s not going to work,” they’re deniers. A study shows that it does work.

Look at COVID. Don’t we all bear some responsibility for talking to our uncle or cousin who doesn’t have the vaccine yet? It would be easier to avoid that conversation. But our best chance of convincing somebody is talking to somebody who already trusts us, loves us. If you can make progress, that’s terrific. If not, you at least tried. We need millions of oars in the water on this problem.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.