Biden’s Top Four Priorities, Explained by Leading BU Experts

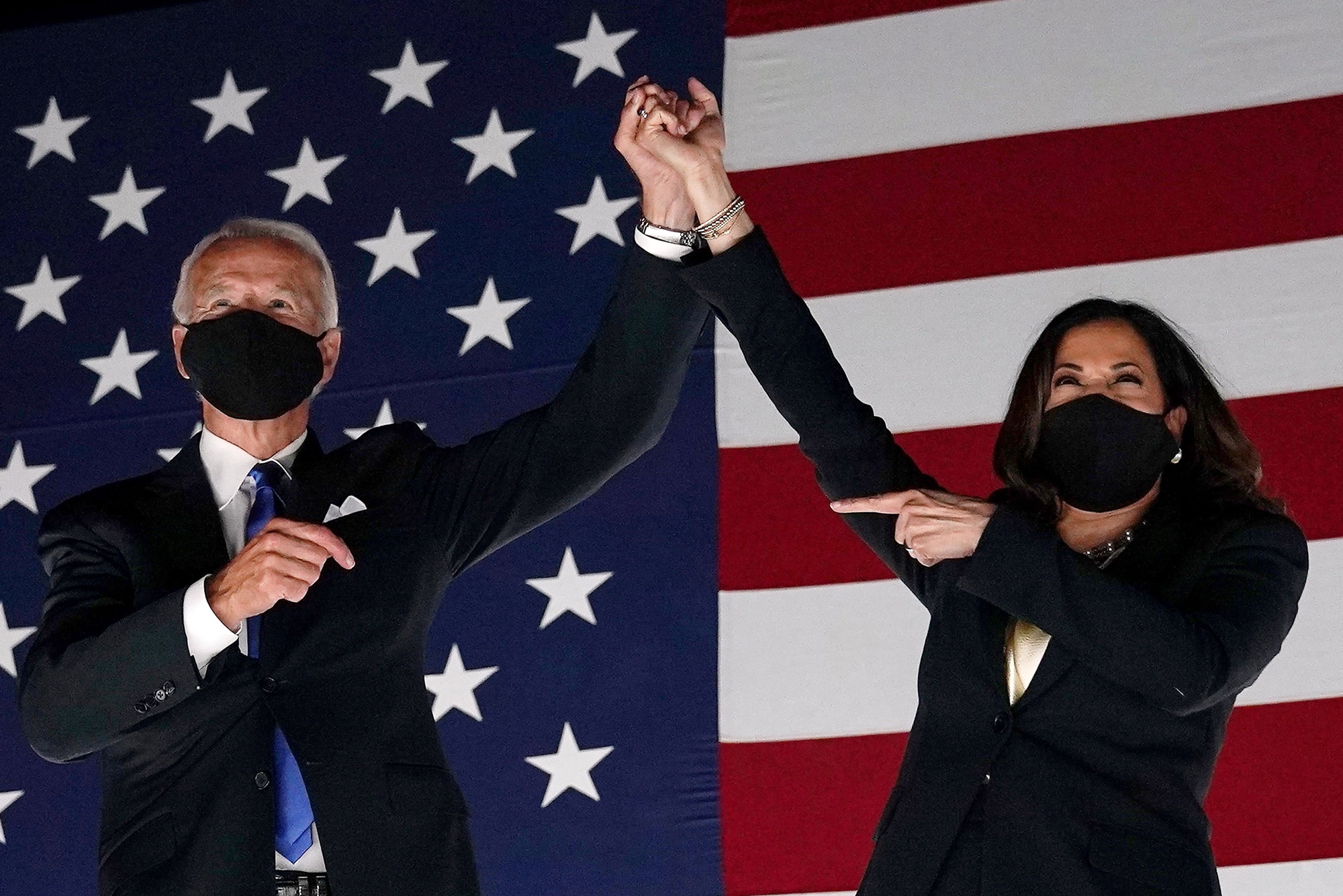

Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, celebrating after being nominated at last summer’s Democratic National Convention, have begun tackling the pandemic, racism, climate change, and economic recovery. Photo by Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

Biden’s Top Four Priorities, Explained by Leading BU Experts

The president-elect lists COVID-19, racism, climate change, and the economy as his most pressing issues

Shortly after their November election victory, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris signaled that there were four urgent, out-of-the-gate priorities their administration would address. Their pledges on each are expansive and ambitious. But achievable? Here is what they have said about each:

COVID-19: Free testing for Americans, ramped-up personal protective equipment (PPE) production while ensuring future American manufacturing of PPE, and “equitable” vaccination.

The economy: Aid to states, localities, and businesses; investing in education and healthcare; and making good on an infrastructure upgrade.

Racial equity: Ensuring access for people of color to jobs, homeownership, higher education, retirement savings, and other necessities.

Climate change: Spending on clean energy, building retrofits, and green infrastructure, while helping communities that bear the brunt of pollution.

An ambitious menu, certainly. But are Biden and Harris targeting the best step in addressing each problem? As their administration prepares to take office on January 20, BU Today asked University experts on each priority to evaluate the Biden-Harris approach and offer their thoughts on the issue.

Free vaccinations will halt COVID-19, says Paul Shafer, a School of Public Health assistant professor of health law, policy, and management.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been engaged with its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to prepare COVID-19 vaccine recommendations once the Food and Drug Administration has approved one or more vaccines for use in the United States. (Vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have been approved for emergency use authorization.) An ACIP recommendation is critical because it provides the mechanism for the COVID-19 vaccine to be free to patients with private health insurance through the Affordable Care Act’s preventive service coverage requirement, even after the public health emergency declaration ends.

This would not help those in Medicare or Medicaid, or the uninsured; however, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently pledged to make it cost-free to all, at least for the duration of the public health emergency. But it is going to take several months, if not longer, to near-universally vaccinate our population, and that may extend beyond the formal end of the emergency declaration. The incoming Biden administration has a plan to “ensure that every person, whether insured or uninsured, will not have to pay a dollar out-of-pocket for…any eventual vaccine,” and this is critical to successful and equitable distribution of the vaccine.

There is considerable work to do to overcome the mistrust and misinformation among many that may lead to hesitancy about getting vaccinated, particularly among people of color, so we cannot let the cost of the vaccine and health insurance coverage be additional barriers.

We need better data on victims of racial inequity, says Jasmine Gonzales Rose, a School of Law professor of law and BU Center for Antiracist Research associate director of policy.

Police violence, COVID-19, and climate change are all life-and-death issues which have a grave, disparate impact on people of color. There are undoubtedly racist policies which facilitate these racial impacts and that need to be replaced with antiracist policies. At the Center for Antiracist Research, we define a “racist policy” broadly as any measure that leads to, or maintains, racial inequity or injustice. By contrast, we define an “antiracist policy” as any measure that leads to, or maintains, racial equity or justice. There is an often overlooked pernicious and unifying policy behind police, health, and environmental problems that needs to be discontinued: the failure to collect racial data.

We cannot evaluate whether policies are racist or antiracist without knowing the race and ethnicity of victims. We need to know how many of the people who die in the grasp of police, from COVID-19, or from environmental degradation are people of color. This information needs to be collected using sound methodology and uniform standards.

For example, Latinxs are the largest racialized minority in the United iStates, but many federal and state entities and jurisdictions do not collect accurate racial data for them. To group Latinxs with whites in data collection is to obfuscate structural racism in two major ways. First, the impact of police violence, COVID-19, and climate change on Latinxs is not revealed. Second, it makes it look like these problems are more evenly distributed across racial groups when they aren’t. If Latinx victims are grouped with whites, then the disparities between white people and Black people appear less significant. The failure to collect racial data is a policy to perpetuate and hide racial injustice. This needs to end. Racial data needs to be collected and analyzed, so that antiracist policies can be crafted and implemented.

We must get women back to work, says Patricia Cortes, a Questrom School of Business associate professor of markets, public policy, and law and a Dean’s Research Scholar.

The pandemic has been especially devastating for the labor market outcomes of women. First, women were more likely to work in sectors that were most negatively affected by the pandemic, such as leisure and hospitality, health services, and retailing. Women represent 47 percent of the labor force, but made up 54 percent of initial coronavirus-related job losses. Second, as mothers still perform most of the childcare responsibilities, the pandemic-induced increase in the need to supervise and care for children drove approximately 2.2 million women out of the workforce between February and October of 2020 and many more to lower their hours worked. Female labor force participation is at a 32-year low, a huge setback to gender equality.

This setback does not only harm women and their families—it has a high cost in terms of economic growth and productivity, as the economy loses millions of talented workers. Additionally, being out of the job for a period of time, and in particular during a recession, can have long-lasting consequences in terms of future wages.

Bringing these women back into the workforce should be one of Biden’s main priorities. A major constraint to reach this goal is the crisis facing the childcare sector. Operating at lower capacities, even as costs rise, has led many centers to close permanently. Although the latest stimulus package approved $10 billion to support the industry, experts claim it is far from enough. The Biden administration should work with Congress to provide the aid necessary to avoid a permanent and dramatic contraction of this vital sector. Without a safe place to take their children, women will not go back to work.

In the longer run, the country needs structural reform of the childcare and early education sector. The United States lags behind other developed countries in the provision of high-quality, affordable early childhood education. Early childhood programs are not only key to allowing parents, mothers in particular, to participate in the labor force—more importantly, they contribute to the long-term success of children, the future productive members of our society.

Climate change is global and the United States must rejoin the Paris Agreement, says Gregory Wellenius, an SPH professor of environmental health.

With heat waves, hurricanes, wildfires, and other extreme weather events threatening ever-more people, climate change threatens our health and nearly every aspect of the way we live, work, and play. Climate action has never been more urgent. Accordingly, the Biden-Harris administration needs to act decisively on both the global and domestic scales.

On the global stage, the new administration has already signaled their intent to recommit to the Paris Agreement, which sets the ambitious goal of limiting global warming to well below two degrees centigrade.

The Biden team will need to implement substantial policies and regulations in order to limit our own greenhouse gas emissions and dramatically reduce our own dependence on fossil fuels. Doing so represents a formidable challenge, but also an unprecedented opportunity to help communities across the country become healthier and more equitable, sustainable, and resilient—better places to live. As the COVID-19 pandemic shows, we also need to dramatically improve our ability to respond to large-scale health emergencies and natural disasters through significant investments in public health, emergency management, and healthcare capacity.

It is in our own self-interest to act decisively to limit further warming and to better prepare for the unavoidable consequences of climate change. The Biden-Harris team has an unprecedented challenge ahead, but also an unprecedented opportunity to build a better tomorrow for us all.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.