A Yellow Rose Project Marks Centennial of 19th Amendment

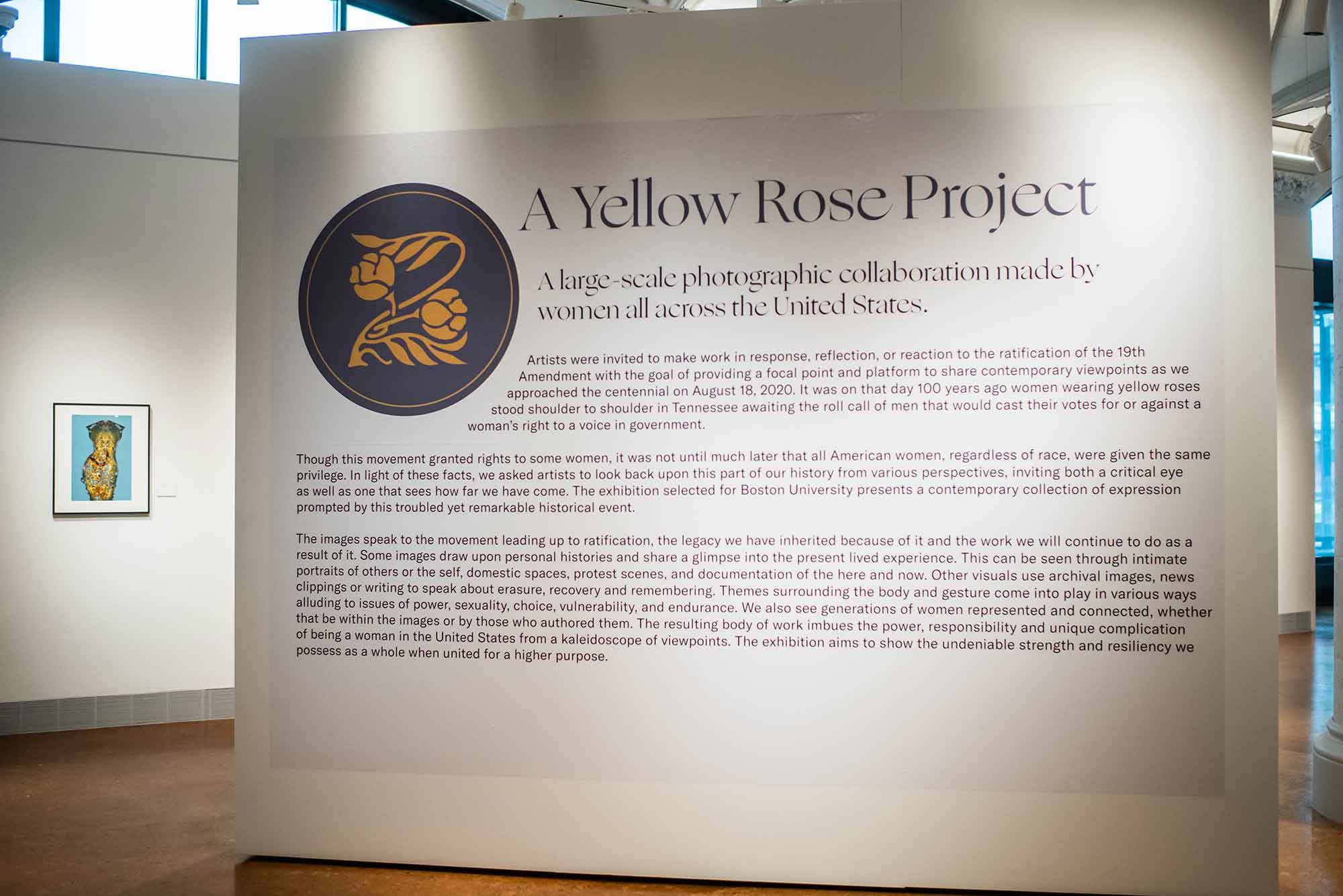

The title wall at the Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery displays the curatorial statement for the show, A Yellow Rose Project. The statement was written by Frances Jakubek, one of the cofounders of the show.

BU Art Galleries Exhibition Marks Centennial of 19th Amendment

For A Yellow Rose Project, women artists from around the US were asked to reflect on historic moment

Last August marked the centennial of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, which prohibited the country from denying citizens the right to vote based on their sex, thus paving the way for women to vote. A fascinating exhibition, A Yellow Rose Project, currently on view at the Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery at Boston University, explores how that historic moment continues to play out more than a century later.

The show, a large-scale, photographic collaboration by women artists from across the United States, uses the centennial to reflect on American womens’ past, present, and future.

Upon entering the gallery, one of the first works that draws the eye is an image by Toni Pepe, a College of Fine Arts assistant professor of photography who is responsible for bringing the exhibition to BU. Titled Mrs. Nixon, the work—a photo of a news clipping—recalls a meeting between President Nixon’s wife and members of the United Nations’ Commission on the Status of Women.

Pepe was one of more than 100 artists who were asked to contribute work for the original A Yellow Rose Project, which toured galleries across the country in 2020. The show’s name pays tribute to the women who stood shoulder to shoulder in Tennessee on August 18, 1920, wearing yellow roses, as they awaited the roll call by the men who would determine the fate of the 19th Amendment. After a final showing in New Mexico, the project was set to wrap up when Pepe brought it to the attention of Lissa Cramer, managing director of BU Art Galleries. As it turned out, Cramer had an available opening in the Stone Gallery’s calendar and decided to bring the show to Boston.

Since the show had already ended, all of the pieces had been returned to the artists. Recreating the exhibition in the Stone Gallery space took a lot of hard work, Cramer says. Along with the two cofounders of the show, Meg Griffiths and Frances Jakubek, Cramer got back in touch with all of the photographers. Realizing that it would be prohibitive financially to transport work from 100 artists around the country, she came up with a solution—choosing just 39 photographs from the original show and including images of the others on a screen in the gallery.

“Everyone still gets to participate, this is just our version of the show. And I have to say, I’m just so happy with how it turned out,” says Cramer. “I just wanted to make sure that all the women got their day in the sun, even if they couldn’t physically have a work on site.”

The resulting exhibition is as diverse as it is colorful. The collection includes traditional photographs, as well as images that have been manipulated with double exposure, ink, paint, or digital tools. The one thread that connects them is that they all address the presence of womanhood.

When Griffiths and Jakubek first approached Pepe about contributing to the original project, the artist had been experimenting with work based on discarded press photographs she found on eBay and at flea markets.

“These photographs are beautiful objects,” says Pepe. “They are littered with crop marks, and date stamps, and all sorts of caption and text information. What I was most interested in was the push and pull between the image and the text.”

For Mrs. Nixon, Pepe selected a press photograph from May 8, 1969, depicting women carrying banners, shouting, chanting, and marching in front of the White House. The photo’s caption reads: “Representatives of the National Organization for Women carry scarves and chant for equal rights for women as they protest outside the White House Wednesday. Inside the mansion, Mrs. Nixon was meeting with the Commission on the Status of Women. She said she doesn’t think there’s discrimination and neither does the President.”

The date is stamped across the image, and a pencil mark is scribbled on the page. By pinning up the newspaper clipping and backlighting it, both the front and back of the page are simultaneously visible in Pepe’s photo of the image. This technique prioritizes the text, which is darker and sharper than the background picture.

Pepe says that by photographing newspapers and not just the original press photographs, she’s able to show how issues like the National Organization of Women protest were presented to readers at the time.

“I was really honored to be included in this project, mainly because it wasn’t just this pure celebration, but was also kind of a critical evaluation of our history of this moment in history, so that we can view it in a more nuanced way,” says Pepe. “There were people who were celebrating this and who were in the fold as a part of this movement. And then there were people who were excluded.”

Other pieces in the exhibition include one by Houston-based photographer Keliy Anderson-Staley, who uses a wet plate collodion process to create tintype and ambrotype portraits. Daniella shows a woman staring at the camera with a slight smile and focused eyes. The image is from a series Anderson-Staley did that portrays, in her words, “images of women confident in who they are. Their strength and independence, apparent in their expressions, is emblematic of the power of their vote.” Another photo, by Cindy Hwang, Forgotten Suffragette No. 3 Tye Leung (New York Tribune, March 6, 1910), honors women activists of color who were overshadowed in the written history of the suffrage movement. Hwang, who immigrated to the US from Korea in 1975, is perhaps best known for her Kyopo project.

The exhibition includes numerous images that chronicle women’s lives today, including a portrait from Sara Bennett’s powerful series, LOOKING INSIDE: Portraits of Women Serving Life Sentences. Taken in 2018, the portrait shows a 35-year-old woman inmate named Assia at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in New York, photographed in the prison’s storeroom for baby clothes. Assia is a nursery aide and doula at the prison, where she is serving 18 years to life. Bennett, a former criminal defense attorney, turned to photography to tell the story of incarcerated women. The photographs for this series all feature women who have lost their right to vote due to incarceration.

Photographer Patty Carroll’s Flagged Down seems to jump off the wall. Known for her saturated photographs, this work shows a woman dressed in red, white, and blue lost in a room covered in American flags. It’s a disturbing, turbulent image. We don’t see the subject’s face, and the dozens of flags that surround her seem to engulf her.

An image titled Resistance, by Ileana Doble Hernandez, continues the exhibition’s theme of merging the past and present fight for women’s rights. It depicts pro-life and pro-choice protesters divided by a line of police. On one side, a sign reads, “Abortion is murder,” and, on the other side, a single figure holds a sign that says, “Keep abortion legal.” Superimposed next to this figure is a woman suffragist from an old photograph. The sign that she holds in solidarity reads, “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

A Yellow Rose Project invites us to reflect on how far we’ve come—and how much further we have left to go in the fight for equality.

Both Cramer and Pepe hope that members of the BU community get a chance to see the show before it closes on September 15. (Currently, the show is limited only to BU students, faculty, staff, and alumni due to the COVID pandemic, but the gallery will open to the general public beginning Monday, August 16.) Until then, there is a 3D, interactive tour of A Yellow Rose Project available free online. In addition, four School of Visual Arts graduate student interns at BU Art Galleries have created Instagram posts where viewers can get more information about the individual artists and their work.

“This show is about the 19th Amendment and celebrating women’s right to vote and emphasizing how important it is—especially in the past year that we had with the election—to remember that [voting] wasn’t a right we always had. A hundred years isn’t long ago,” Cramer says.

A Yellow Rose Project is on view at the Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery, 855 Commonwealth Ave., through September 15. The gallery is open Monday through Friday from 11 am until 5 pm. All visitors are required to wear masks. Admission is free.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.