Humor and Honesty Help Fix a Fractured Relationship with Mom and Dad

As a child, Deb had a fraught relationship with his parents, immigrants from India. They had an unhappy marriage and divorced when Deb was in high school; his father moved to Kolkata in 2007 without telling anyone. Photo by Amy Lombard

Humor and Honesty Help Fix a Fractured Relationship with Mom and Dad

In his new memoir, Missed Translations, New York Times writer and stand-up comedian Sopan Deb (COM’10) writes about building a relationship with his immigrant parents

When Sopan Deb isn’t writing about basketball and culture for the New York Times, he moonlights as a stand-up comedian. A few years ago at the Big Brown Comedy Hour, which showcases emerging comics of South Asian and Middle Eastern descent, Deb, who is Hindu American, told a joke that went like this:

My favorite Christmas tradition growing up was asking my mom what the meaning of Christmas was. Every year, we’d be like, “Hey Mom! What’s the meaning of Christmas?” She’d go, “Oh, it’s when Jesus died on the cross.” We’d say, “Oh, why did Jesus die on the cross?” She’d answer, “It’s because Jesus became a carpenter instead of a DOCTOR!”

Aside from the fact that it confuses Christmas and Easter, the joke plays into the stereotype that Indian moms want their children to become rich and powerful. The bigger issue was that the conversation never happened: Deb’s childhood in a New Jersey suburb with his brother and their immigrant parents didn’t have many traditions or warm, fuzzy moments. What Deb (COM’10) was unwilling to joke about that night was his fraught relationship with his parents, who had a miserable arranged marriage and divorced when Deb was in high school. He and his brother, Sattik, who was 10 years older, had a warm relationship, but because of the age difference, Sattik wasn’t around much during Deb’s formative high school years.

While his stage routine leaned on his South Asian culture, it ignored the instability and scars his upbringing left. Deb grew up angry and embarrassed by his mother and father and his family’s culture; he glorified whiteness, which he equated with happy homes (the kind his friends seemed to have) and close family ties.

When he was doing the stand-up routine, “sometimes it felt like I was playing the part of a brown guy onstage, but when I dropped the façade and delved into my actual life, the words deflected the guilt and vulnerability I wasn’t yet ready to face,” Deb writes in the first chapter of his debut book, Missed Translations: Meeting the Immigrant Parents Who Raised Me (Dey Street Books, 2020), a funny, poignant memoir about his attempts, as he neared his 30th birthday, to make amends with his parents and build the kind of relationship he never had with them growing up.

Throughout Deb’s decade-plus of reporting politics, culture, and sports, he has interviewed subjects like Bill Murray, President Donald Trump, and basketball stars Stephen Curry and Bill Russell (Hon.’02). It was during his wide-ranging Q&A with the cast of Arrested Development that actor Jessica Walter alleged that her costar Jeffrey Tambor had verbally harassed her during filming. The story went viral.

Those interviews weren’t nearly as complex as the ones he had with his parents. As Missed Translations opens in January 2018, Deb explains that he had barely spoken to his mother, Bishakha, and his father, Shyamal, in years. His father had moved to Kolkata in 2007 without telling anyone. Deb hadn’t thought much about their strained relationships until he started joking about his family onstage in 2013. But these bits were what made him realize that he knew close to nothing about their histories or what they had hoped their lives would be. And so when he was invited to a friend’s wedding in India in the summer of 2018, months after he first performed at the Big Brown Comedy Hour, he agreed to attend, along with his girlfriend (now fiancée). Maybe he could meet up with his dad and explore his parents’ native country. That Mother’s Day, he called his mom, who lived two hours away in a New Jersey suburb, and asked how she was doing.

“I felt like I was finally at a point in my life where I had space in my heart to make room for my parents,” Deb says. “So I decided to reach back out to them, and I thought of documenting it in a book, because I really wanted to capture everything as I was experiencing it. I had no idea how it was going to go because some parents can be very stubborn. A project like this required me to look inward.”

Some of the issues Deb writes about are common to immigrant families. He recalls moments of being embarrassed when his parents hosted Bengali family gatherings, wearing their saris and dhotis. Other struggles are more universal, such as his mother’s depression, which only became clear to him later in life, and the stress his parents’ troubled marriage caused him and his brother as children.

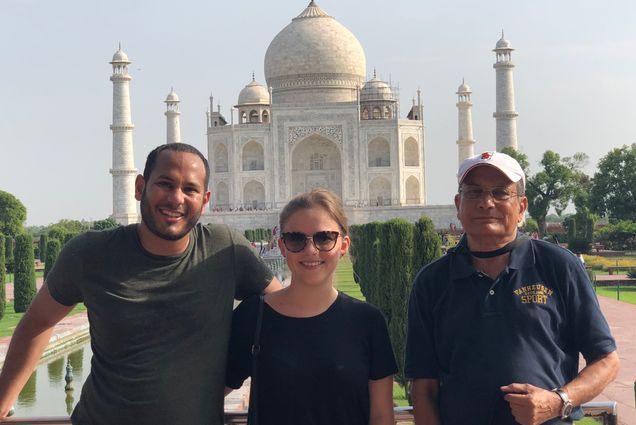

In 2018, Deb and his fiancée, Wesley Dietrich, traveled to India, where his father had moved years earlier. During their five-city tour, the three visited cultural sites like the Taj Mahal.

The book has received strong reviews, with the Library Journal writing that Deb’s “writing style is plain, confessional, and filled with laugh-out-loud passages about everything from memories of his childhood to learning to accept his insecurities as an adult. Perhaps most impressive of all, Deb addresses firsthand experiences of ignorant racism with wise humor.”

The accolades don’t surprise Susan Walker, a College of Communication associate professor of journalism, who taught Deb in two COM classes, and describes him as tenacious. She cites the time Deb was studying abroad in BU’s London program and covering the G20 protests in 2009. Nothing had happened for hours, so his fellow reporters gave up and went home. At Walker’s urging, Deb stuck it out. He got footage of the local British police clashing with protesters, and his tape was used by local lawyers to prove that their clients were peacefully protesting. “He just worked harder than anyone,” she says.

A Trump Bump

Growing up in the New Jersey suburbs, Deb remembers being the only “brown person” in his high school of 1,600. He found it tough to fit in, and the outsider mentality followed him to BU. “Because I had grown up in such a challenging household, I didn’t learn how to make meaningful connections with people, so I struggled making friends, I struggled keeping friends,” he says. “I was very much a loner throughout college. It took me until my mid-20s to start coming into my own and figuring out who I was. I’m sure a lot of people figured that out in college.”

After graduating from COM, Deb worked for news outlets like the Boston Globe and Al Jazeera America. In 2015, CBS hired him as one of its embedded reporters covering the early days of the Trump campaign, a stint that would put Deb’s reporting on the national stage. He soon gained a reputation for his ability to furiously transcribe Trump’s rambling speeches and interviews, and tweet them out in almost real time.

Growing up, we barely spoke. To me that wasn’t unusual, except when I would tell people about it, I’d say it casually and they’d tell me how weird that was.

“It was unlike anything I had ever seen before,” he says. “We went to more than 40 states, hundreds of rallies. I can’t even properly explain what that part of my life was like, because it was new for all of us, new for the world. The rallies were like political rock concerts. People would line up the night before, they would dress like Trump, they would bring signs. Trump would come up to the podium, point to people in the crowd, people would be in tears. I’m proud of my work covering the Trump campaign, but it was an exhausting year and a half, covering that news cycle every day.”

Deb’s reporting gave him what Columbia Journalism Review called a “Trump bump.” After the election, he fielded three job offers: for the CBS White House press corps, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, and the New York Times. He joined the Times in January 2017.

Working at the Times and about to turn 30, Deb found himself thinking more about his parents, then in their 70s, and their family histories. Why did they come to America? Why was his relationship with them so troubled? Even if their home life had been happier, he believes, things probably wouldn’t have been easy. After all, Deb, who was born in the United States, and his parents come from very different worlds. On top of that, he says, was his mother’s depression. No one in her family seemed to know how to help her, and there wasn’t a strong Indian community in their New Jersey town to support her. The four people living in his childhood home never asked about one another’s day, and they became more distant and bitter over time. “Growing up, we barely spoke,” Deb says. “To me that wasn’t unusual, except when I would tell people about it, I’d say it casually and they’d tell me how weird that was, that it wasn’t a normal thing to grow up with.” He knew then that he wanted to get to know his parents before it was too late.

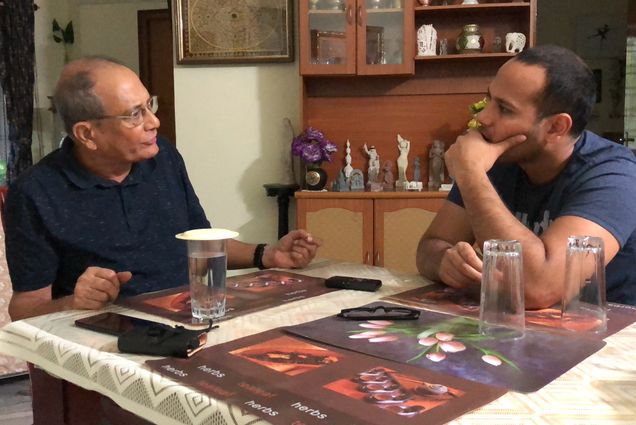

With the planning underway for the trip to India, Deb reached out to his father and mother. They seemed pleased to hear from him, although their initial conversations were awkward. By that point, Deb decided to chronicle their reuniting in book form. They were open to the idea, at least in the beginning. “I made it very clear to them the entire time what I was doing. I also made it clear that they were getting an unvarnished look, and that I wasn’t going to pull any punches,” Deb says. “But even when you agree to that, once you read it, that understanding goes out the window. So I think both of my parents had a difficult time reading the manuscript, but at the end of the day I think they understood what I was trying to do.”

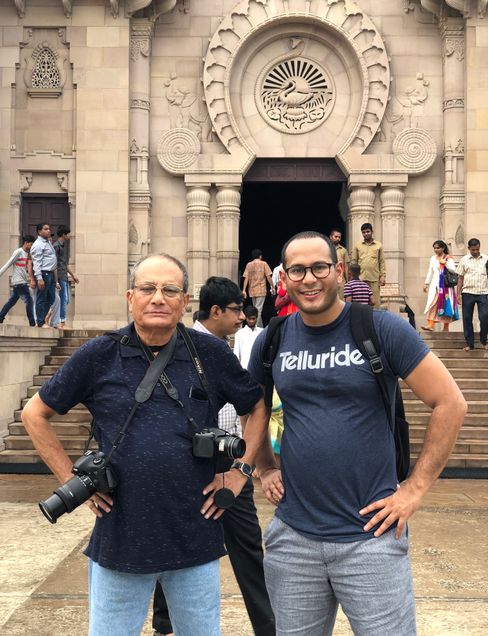

When Deb arrived in the city of Kolkata with his fiancée, Wesley Dietrich, he was prepared to meet the frail old man he remembered from the last time they were together. But he was in for a shock. His father looked “tan, rested, and healthy,” Deb writes in his memoir. “He didn’t have a Dad-Bod….He had the kind of glowing, confident tan of someone who had strolled onto a golf course smoking a Cohiba.” After greeting his son warmly, his father said it looked like his son had put on weight (Deb went out for a run the next morning). Through their five-city tour, they visited cultural sites like Belur Math and the Taj Mahal. Deb learned his father had nine siblings, and he met cousins. He asked his father about his troubled marriage, and spoke candidly about his unhappy childhood. Deb took responsibility for not reaching out more, and his father listened and did some apologizing of his own.

Back in the States, Deb met up with his mother, too. He learned that she had been placed in the arranged marriage by her mother and had never been encouraged to find a career. She’d had very little say in her own life.

“In the course of this journey of interviewing my parents and reconnecting with them, my parents became humans to me instead of just a footnote,” he says. “I found myself taking a lot more pride in where I came from. I’m not saying there aren’t parts of the culture that make me feel uncomfortable—there are. The cultural implications failed my parents in many ways. I am in large part who I am because I tried to break the mold in that respect. But there are many parts that I’m very proud of—I’m bilingual. And parts of my parents’ personalities are shaped by the culture. This journey was less about heritage, more about forgiveness. That to me was the most meaningful thing.”

He didn’t have a Dad-Bod. He had the kind of glowing, confident tan of someone who had strolled onto a golf course smoking a Cohiba.

One theme Deb revisits throughout the book is why he rejected his South Asian roots growing up. “I had this irrational thought in my head: being brown and being Bengali was what brought this unhappiness to my childhood,” he says. “Because my parents were arranged to get married, and my fiancée’s parents were not arranged to get married, I would like to be white, because all my white friends, they had better lives than I do.”

But through his visits, Deb was able to have some significant and meaningful conversations with his mom and dad and learn many of the reasons for their unhappiness. He better understands his Indian heritage now as well, and proudly touts it. And although their relationship is still a work in progress, his parents have become part of his daily life.

His stand-up material has improved, too; it’s become more nuanced, he says. And he no longer sees his parents as simply the punchlines of his jokes.

“In the grand scheme of things, they’re humans to me, and that is such a big change from where we were two or three years ago,” Deb says. “Are we as close as a lot of parents are with their kids? No, I’m not sure that gulf will ever be bridged, but it’s certainly much better than it used to be.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.