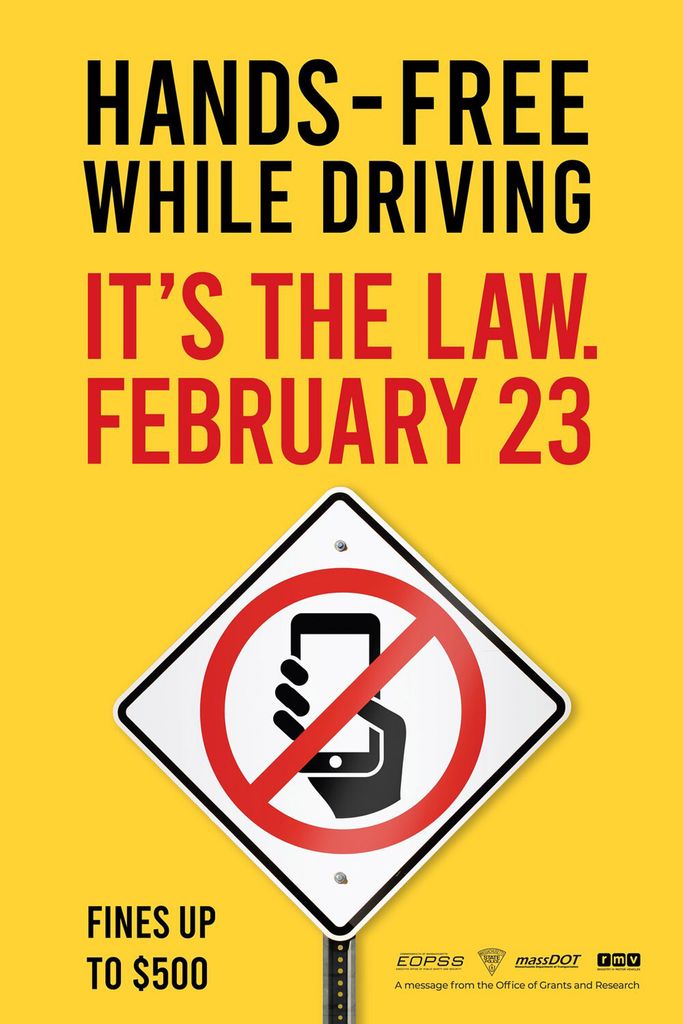

New Law Requires Drivers to Use Phone Hands-Free in Bid to Reduce Distracted Driving

A new Massachusetts law taking effect February 23 requires Bay State drivers to do the right thing and use a hands-free device for all cell phone use. Violators will face substantial fines—after a grace period that runs through March, during which everyone gets a warning. Photo by LPETTET/iStock

Listen Up: New Law Requires Massachusetts Drivers to Use Phones Hands-Free

Starting February 23, violators will face significant fines in push to reduce distracted driving

A new Massachusetts law bans hand-held cell phone use by drivers and backs it up with significant fines in an attempt to reduce distracted driving.

Beginning Sunday, February 23, drivers in the Bay State will be required to use Bluetooth or other hands-free technology if they want to talk on their phone while operating a motor vehicle.

“As a citizen, I think anything that gets people to put down their phones and pay attention to their driving is a step in the right direction,” says Kelly Nee, chief of the BU Police Department. “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, distracted driving caused an average of 9 deaths and 1,000 injuries a day in 2018. We see it constantly.”

Violators face fines of $100 for a first offense, $250 for a second offense, and $500 for a third. Second- and third-time offenders will also be required to take a distracted-driving class. A third offense can also result in an insurance surcharge. (Find details here.)

The BUPD doesn’t have authority to police routine traffic violations, but Boston, Brookline, and State Police do, as well as police in all other municipalities in the commonwealth. The law signed by Governor Charlie Baker in November expands on an existing prohibition against texting while driving, which has proven difficult to enforce. Now simply holding a phone to your ear while driving will be enough to get you pulled over.

There’s a grace period of just over a month to allow drivers to get with the program: through March 31, police will hand out only warnings—although texting can still get you fined during the grace period.

Under the new law, drivers can touch their phones once to activate hands-free mode, and they can use one earphone or earbud. They can also touch the phone to control GPS apps like Waze, as long as the phone is in a holder, such as on the dashboard or windshield, rather than in their hand. But touching the phone is banned for all other uses, including texting, emailing, video, games, and the internet.

You may use your phone normally while the vehicle is stopped and not in a travel lane—but not at red lights or stop signs.

And remember: drivers under 18 are not allowed to use electronic devices at all while behind the wheel, even in hands-free mode.

Massachusetts was ahead of the curve with its 2010 texting ban, but has fallen behind many states on the hands-free issue, says Sean Kealy, a School of Law clinical associate professor of law and director of the Legislative Policy and Drafting Clinic.

“Pretty quickly everybody figured out that the 2010 ban was too narrow,” Kealy says. “People were distracted in so many different ways, just holding the phone up to their ears to make a call, but also streaming a movie or typing in an address for their navigation system, as well as just texting.”

It’s going to be a hard habit to break.

People were rarely pulled over, Kealy says, because it was unlikely for a law enforcement officer to be able to see them texting, as opposed to all the other things not covered by that law. Massachusetts Senate Majority Leader Cynthia Creem (Questrom’64, LAW’66) (D-1st Middlesex & Norfolk) was among legislators who began to propose wider hands-free laws. But for several years those bills were held up, Kealy says, by various things, from inertia on Beacon Hill to concerns about how the laws would be enforced.

“Governor Baker expressed this; he was worried that this was going to favor people in higher-income brackets and really discriminate against people in lower-income brackets,” Kealy says. “If you’ve got a really nice car, you can afford that Bluetooth setup, and you can do almost anything by just telling your car what to do. People in lower brackets just didn’t have that.

“I think what changed is that now every car seems to have this type of technology, and if not, you can buy a $20 gizmo at Best Buy and effectively do the same thing,” he says.

The other thing that held up the change was concern about racial profiling. The version of the bill that passed, Kealy says, included a requirement for reporting those statistics that will allow advocates to track whether police are targeting minorities or others in enforcing the law.

He says the grace period until March 31 is actually a recognition of how many people across all social strata use their phones while driving.

“Even law-abiding people like myself,” Kealy says. “I find myself doing it all the time, and it’s going to be a hard habit to break. And I think it’s a recognition of that—that it’s so pervasive. But we’ve got to change behavior sometime.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.