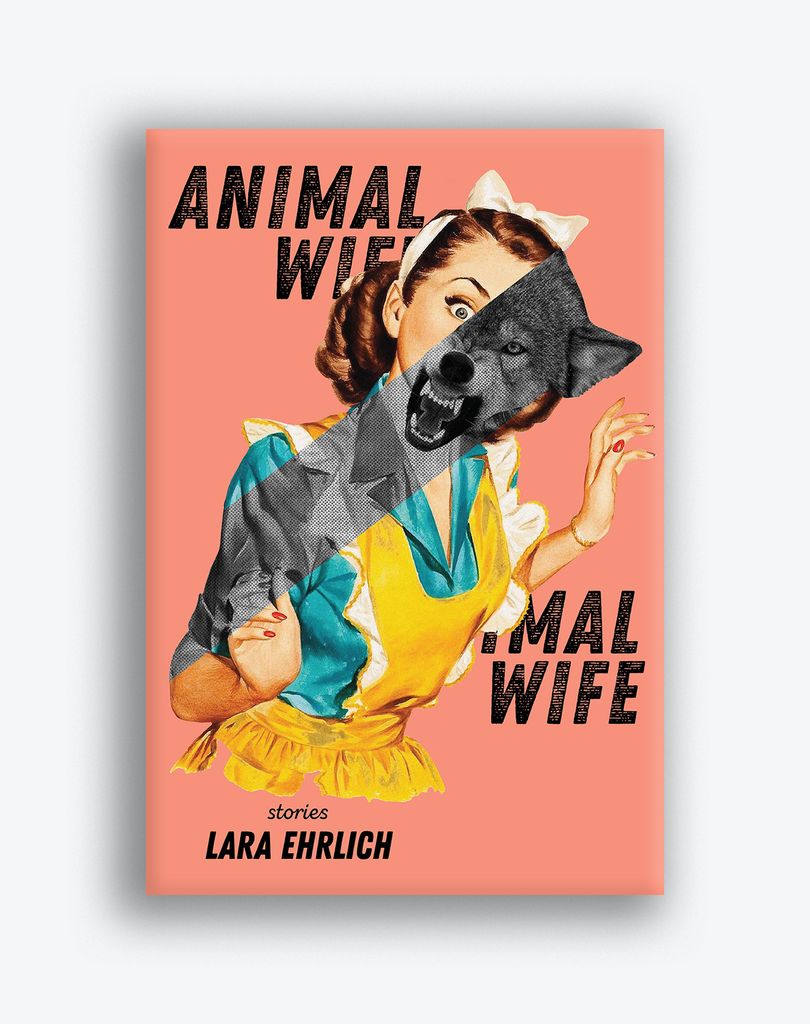

Lara Ehrlich Finds Inspiration in Fairy Tales in Her Debut Collection, Animal Wife

Photo by Janice Checchio

Lara Ehrlich Finds Inspiration in Fairy Tales in Her Debut Collection, Animal Wife

Prize-winning short stories explore the inner lives of girls and women

Lara Ehrlich had a busy spring as director of marketing for June’s International Festival of Arts & Ideas in New Haven, Conn. The 250-event schedule had to be completely reimagined as a scaled-down, virtual festival due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Now Ehrlich (UNI’03), previously a senior editor-writer for BU Marketing & Communications and an associate editor for Bostonia, has something else to think about: the September launch of her short story collection, Animal Wife (Red Hen Press). Ehrlich writes about teenagers finding their way in an alluring yet frightening world and women whose discontent manifests in mind-boggling ways. One goes feral after donning an elaborate deer suit (inspired by a medical exosuit developed at Sargent College). Another shares her house with a bear.

Publication came with winning the Red Hen Press Fiction Award, chosen by New York Times best-selling author Ann Hood, who says of the collection, “It made me dizzy with its exploration and illumination of the inner and outer lives of girls and women.”

Ehrlich, who lives in Connecticut with her husband and four-year-old daughter, spoke to Bostonia about transformations, her obsession with language, and learning to swim like a mermaid.

Q&A

With Lara Ehrlich

Bostonia: The first stories in the book focus on girls. Why?

Ehrlich: My obsession with nostalgia, and that time when you don’t yet understand the things you’re starting to see leaking into your childhood from the adult world, like sexuality, and your body changing, and all these things you have to grapple with. And it can be incredibly scary. It’s like hearing a dirty joke and knowing that it’s dirty, but not knowing why because you don’t have the experience to understand it yet. That’s unsettling and terrifying.

How much of these stories is autobiographical?

Even the stories that are more wildly fantastical have kernels of my own experience. I did have chickens growing up, including one who met me at the bus stop. A weasel did kill them in the middle of the night. I did attend a middle school birthday party at a hotel, where one of the girls went off in a carful of boys she didn’t know. I did work at an office in a suburb of Chicago that was so boring I just drove around aimlessly in my car during lunchtime. I pushed these moments and others together in unexpected ways to see what would happen, and what they would illuminate about each other.

The kinds of transformation your characters experience change through the book.

Yes, the focus shifts to adult women who are questioning their identities and their desires, especially motherhood. And the final third of the book is composed of stories about mothers who are questioning who they are now. That evolution naturally follows my own trajectory as I wrote those stories. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a mother because I was terrified of giving up my passions and independence, of losing every part of myself that makes me who I am. The final third of the book deals with this fear of having lost yourself—some of them are worst-case scenarios in which I used my most desperate fears as the foundation for stories, like “Burn Rubber.”

I’ve always loved fairy tales, not

for the princesses, but for the

creepiness.”

The changes are externalized in wild ways.

I’ve always loved fairy tales, not for the princesses, but for the creepiness. My favorites were Hans Christian Andersen’s works and Italo Calvino’s huge volume, Italian Folktales, both of which are incredibly creepy and full of bizarre transformations: brothers into swans and princesses into statues and women into fish. I’m drawn to these mystic transformations because they often reveal human truths. Fairy tales often emerged from real-life anxieties. Like all the stories about changelings. They came out of parents’ anxiety about a child who wouldn’t stop crying or acting out, and the explanation was that the fairies had taken your child and replaced it with a demon—that got at the existential horror of new parenthood. This soaked into my writing when working on stories about the often-terrifying transformations of puberty and motherhood.

Your prose often takes lyrical flight.

I’ve always been obsessed with language on the level of words and sentences, which is why I’m a very slow writer. In college, I took every poetry class I could. Although I’ve never wanted to write poetry, I love its specificity; how each word, each space between words, each punctuation mark is intentional. I try to bring that intentionality to my writing—which is why it takes me forever to finish a story!

That style serves this kind of magical realism…

I’m really interested in capturing a sense of fuzziness between reality and fantasy. I want to give the reader room to interpret the reality or unreality of a situation—but there’s a fine line between intentional uncertainty and unintentional confusion. I need the reader to know that I’ve intended them to question reality. In “Animal Wife,” for example, I don’t want to answer the question, “Is the mother really a swan or is it all in her daughter’s head?” My intention is that it could be either—and both—and that duality can allow for different interpretations.

You’re working on a novel, and you went to Sirens of the Deep Mermaid Camp in Weeki Wachee Springs State Park in Florida for research. Explain.

It’s about a restless siren who becomes human and has a daughter. When she realizes that her life is still unfulfilling, she takes her daughter and runs off to the coast where she finds a defunct mermaid burlesque—sort of a tank built into the side of a cliff, like Weeki Wachee. And she performs as a siren in this tank and attracts a group of other women who want to perform—and live—as mermaids. But as her daughter matures, she begins pushing back against this world that she has created. Women have been performing as mermaids at Weeki Wachee since the 1950s. I went to siren camp for the specific experience of learning how to swim—as a human—in a tail.

Sounds like it addresses some familiar themes?

Exactly. It’s playing with transformation and motherhood and dissatisfaction. [Laughs] Probably after this one, I’ll shift to something different.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.