Learning on the Front Lines of the Pandemic

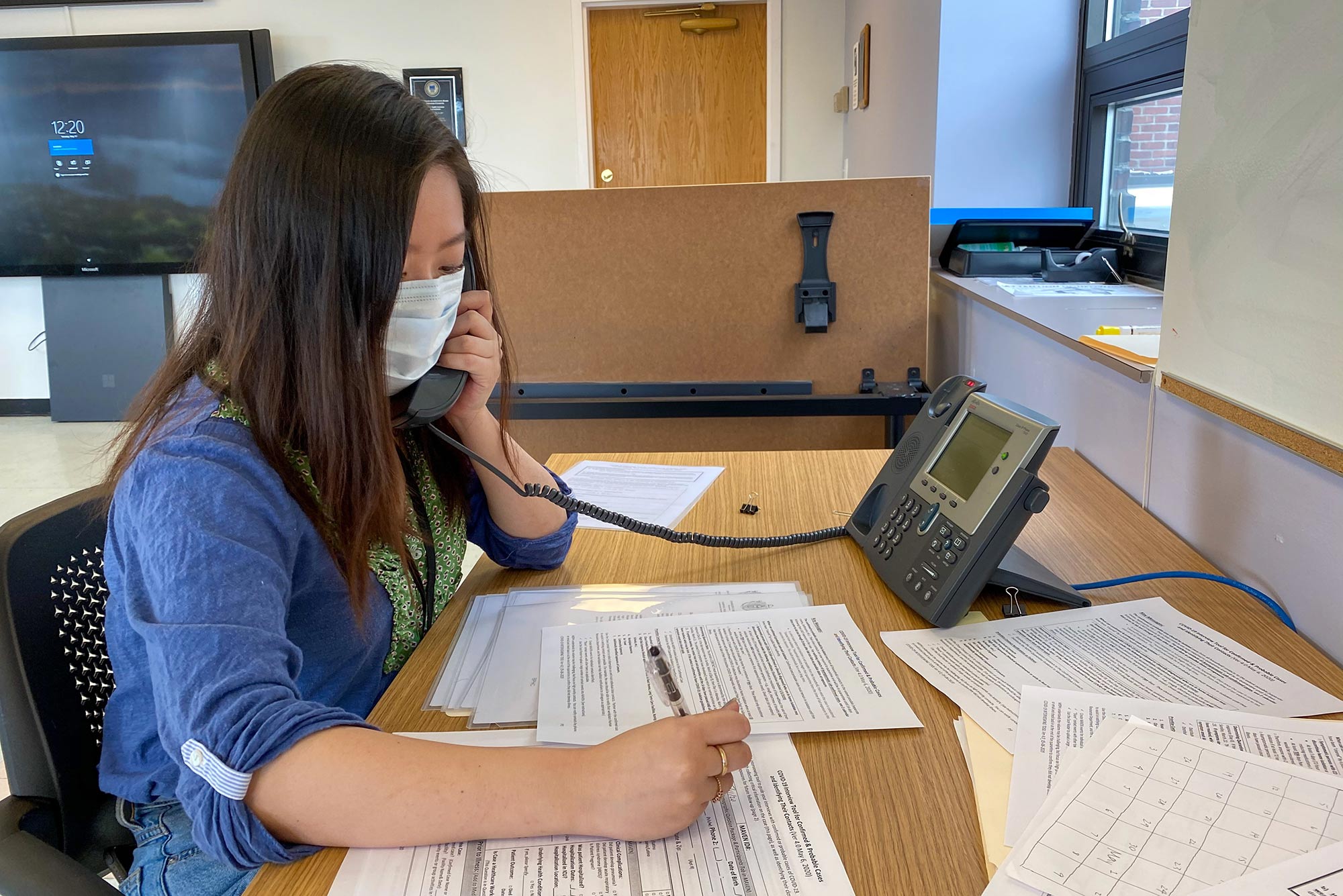

Rinka Murakami (Sargent’20, SPH’21) studied the public health response to Ebola before volunteering as a contact tracer for the city of Boston. Photo courtesy of Murakami

Learning on the Front Lines of the Pandemic

Sargent students volunteer as contact tracers at the Boston Public Health Commission

At the height of the pandemic, when most people were hunkered down in their homes and apartments, a group of 10 Boston University health science students ventured out beyond the confines of four walls to better understand the biggest public health crisis in a century.

The group took a front-row seat by working as contact tracers at the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC), reaching out by phone to hundreds of COVID-19–positive individuals to better understand their symptoms and exposure and to help with the effort to slow the spread of the virus.

Suddenly students were propelled into the private lives of infected individuals—asymptomatic people struggling to quarantine in crowded apartments, families trying to raise children while infected or continuing to go to work out of necessity. And they saw up close the way the disease disproportionately affects people of color and exacerbates healthcare system inequities.

“You feel worse at the end of the day than when you started, because you realize how much is wrong,” says McKenzie Beaton (Sargent’20, SPH’21). “It’s definitely something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

Contact tracing has been a key tool in the effort to stop the spread of the novel coronavirus, breaking the chains of transmission, preventing surges of infections by identifying and helping those closest to the disease. It’s also one of the oldest public health tactics around—the contact tracing program through the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) Infectious Disease Bureau is one of the oldest in the nation and is usually staffed by nurses. When the volume of cases from the COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed the small office, officials reached out to Boston’s higher ed community for help.

Shelley Brown (SPH’07), a Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences clinical assistant professor of health science, thought the opportunity could offer pivotal on-the-ground field experience for students. She emailed a group of students who’d lost internships because of the pandemic or had expressed a desire to help when stay-at-home orders were invoked. Within two hours, more than 30 students volunteered.

“The response was overwhelming,” Brown says. “It was an amazing opportunity for them in a pandemic. And they’re giving back way more than their internship requires.”

The outreach was intensive: the BU volunteers were asked to make calls from a conference room at BPHC’s Dorchester offices for six-hour shifts, three or more days a week. Volunteers were not paid, unlike other contact tracing programs, and the work was draining but rewarding.

Thomas Lane, BPHC Infectious Disease Bureau associate director, says the city works in partnership with the larger commonwealth of Massachusetts Community Tracing Collaborative, operated by the nonprofit Partners In Health and the commonwealth, sending them cases and keeping others for its own staff to trace. That includes nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and high-risk populations, such as the homeless.

“Given the volume of cases coming in, we needed to expand our opportunities to reach people,” Lane says. “A lot of them showed competency in issues around health equality, reaching people, and meeting them where they’re at. We thought they’d be a great asset, and they are.”

Beaton, who is working on a master’s degree, says when the offer came from Brown, she leaped at it.

“I was going crazy not doing anything because I know this is what I want to do with my life,” she says. “I was dying to get to work.”

Her bilingual skills were especially useful. Some of her calls were to Spanish-speaking immigrants—many of whom were not getting needed healthcare services before the coronavirus and and who benefited from advice and fact-based information about how to manage it. Despite that, Beaton says, many people living in small or crowded apartments still struggled to avoid contaminating others.

“This systemic inequality—I’ve been studying it for four years,” she says. “It’s a really hard pill to swallow.”

The contact tracing effort also helps record the demographics of Boston’s infected population, which contributes to broader information nationally about who is infected. A study by the Pew Research Center recently found that while black Americans comprise 13 percent of the US population, they represent 24 percent of the deaths from COVID-19.

Natalia Kelley (Sargent’22), who is fluent in Portuguese, says she tried to let her calls unfold like conversations to build a sense of trust before asking people intimate questions. And she found more often than not that people weren’t hesitant to share their symptoms, and that much of her job was about listening as people shared the details of their lives.

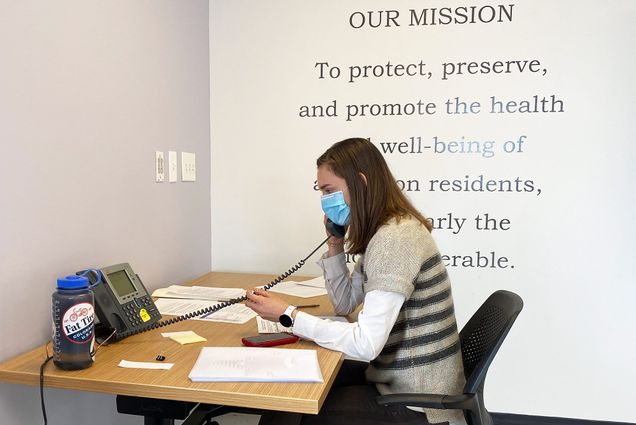

Jessica Schueler (Sargent’21) and Natalia Kelley (Sargent’22) volunteered as contact tracers as part of the city of Boston’s coronavirus pandemic response (left). Kelley appreciates the on-the-ground experience contact tracing gave her (right). “It felt good to do something useful,” she says. Photos courtesy of Rinka Murakami

But it wasn’t always easy. One woman was angry that the city received information about her positive diagnosis. Kelley says many of the calls she made were to healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, and healthcare aides, to ask about their symptoms and remind them of protocols, including that they needed two negative tests for the virus before they would be allowed to return to work. Others shared their symptoms in graphic detail.

“It’s all [laid] right out before us,” she says.

Rinka Murakami (Sargent’20, SPH’21), who is pursuing a master’s degree and is studying epidemiology and biostatistics, says she was surprised by the sheer number of asymptomatic people she spoke to.

One woman she called happened to be on her way to work at a group home. “She said, ‘I’m about to go in today.’ I was like, ‘Please do not go in,’” Murakami says.

Another woman tearfully pondered what would happen to her children if she died from the virus.

Such are the hard realities of the coronavirus up close, where infected people are making difficult choices between exposure and economic survival. Although the coronavirus will be the subject of classroom and academic study for years to come, Murakami says hearing the stories firsthand gave her a new sense of urgency about healthcare injustices.

This systemic inequality—I’ve been studying it for four years. It’s a really hard pill to swallow.

“For me, it was eye-opening, the socioeconomic differences,” she says. “People don’t always have primary care providers to ask all these questions. So, it really highlights the social disparities.”

Kelley, who hoped to work as a nanny this summer, says that on a personal level the work made her feel productive during a bleak time. Off-campus students faced their own isolation after many students left campus, restaurants and businesses closed, and human interactions were mostly limited to Zoom chats.

“I definitely liked talking to people and it’s a good way to feel like I’m doing something useful,” she says. “Everybody feels so stuck, like there’s not much we can do.”

The city offered scripts to the contact tracers, but most participants say their real-life conversations took freewheeling twists and turns. Gillian King (Sargent’20) says delving into a person’s contacts had to be handled tactfully and in a nondemanding manner.

“It got a lot more personal and intense. Asking people, ‘Can you give me your spouse’s date of birth and phone number?’ was odd,” says King, who has since returned to her family’s home in Palo Alto, Calif. “The conversations are definitely not linear. But I found that people actually want to talk.”

Like the other volunteers, King made 25 to 30 calls during her 9 am to 3 pm shift, riding a borrowed bike to get there. Typically, 15 to 20 people answered the calls, she says. Some were desperate for conversation. A firefighter who was under strict quarantine in a hotel room told her he had not left his 10-by-10-foot room for nearly two weeks and that King was one of his few human interactions.

In fact, many were comfortable right away talking about their health symptoms, whether diarrhea, excess phlegm or mucus, or other less-than-pleasant topics, because they wanted to help. While such information is highly personal, King says it also helped that the coronavirus doesn’t hold a stigma like a sexually transmitted disease or HIV might.

“I think everyone feels a personal responsibility to do what they can,” she says. The enthusiasm to discuss the symptoms sometimes even bordered on eagerness and excitement, as the pandemic spread. “It was like the new purse: if you don’t have it, who are you?”

Murakami, who had been an intern working on HIV services with the city health department since January, says the experience only reaffirmed her desire to work in healthcare among the most vulnerable populations. She had previously worked on a research project for the World Health Organization, studying the response to Ebola and how one African burial ritual involved leaving corpses outside for mourners. It was later discovered that the time right after death was one of the disease’s most infectious periods.

On the cusp of a career in public health, she also wonders what missteps are being made in addressing the current pandemic, especially when so little is known about the disease and symptoms are so varied.

“It’s interesting having that perspective,” she says, “and I wonder what we’ll look back on in a few years.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.