BU Spark! Hacking COVID-19

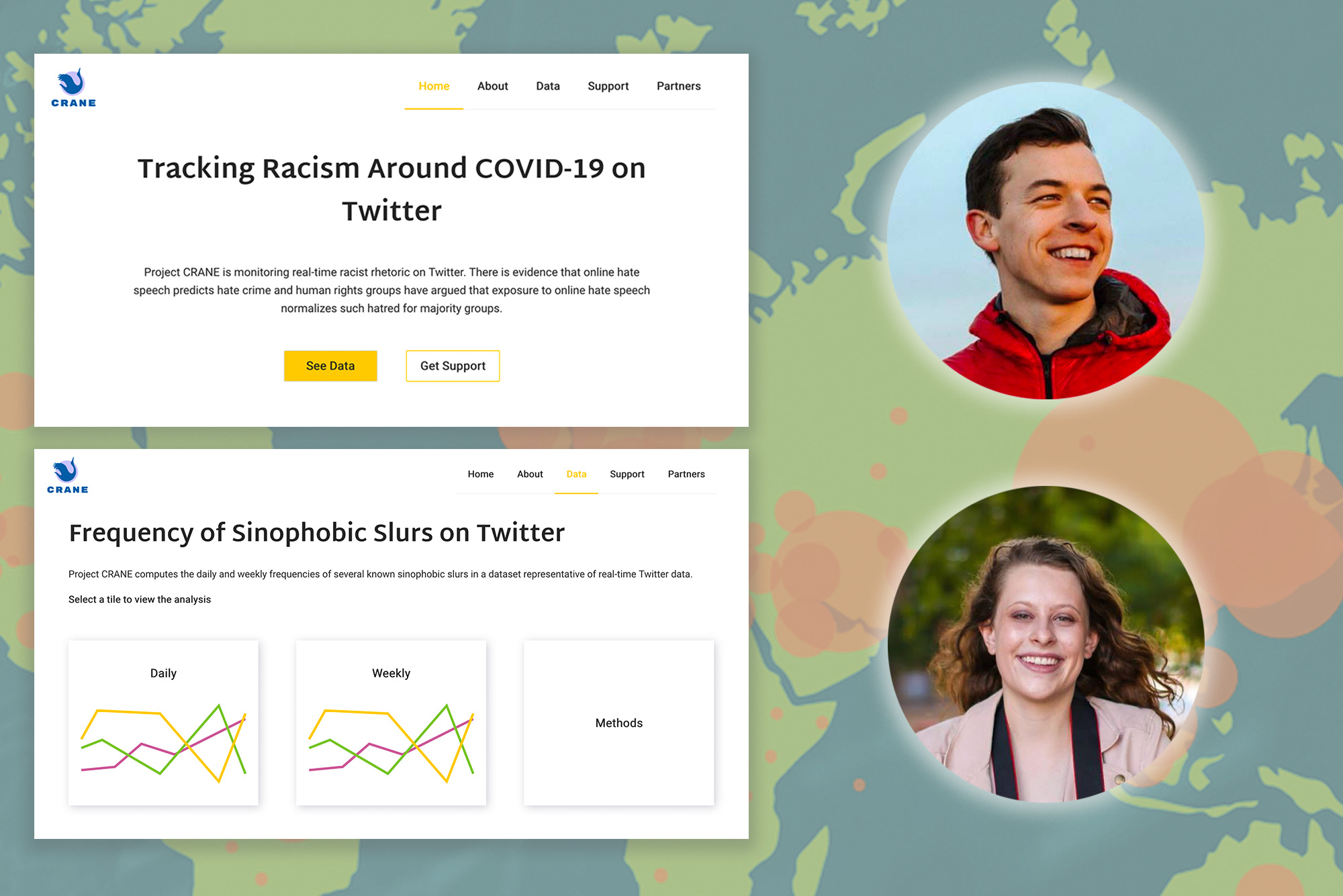

Project Crane team members Ian Saucy (CAS’21) and Rachael Dier (COM’20), with a screen shot from their project. Photos courtesy of BU Spark!

BU Spark! Hacking COVID-19

Students, others join Resiliency Challenge to find innovative solutions in coronavirus crisis

One group of students made an app to track anti-Chinese bigotry on social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Another built a chatbot to make it easier for immigrants to get information about COVID symptoms. Others worked on contact tracing, 3D printing to produce personal protective equipment, and turning high school students into remote teacher’s assistants on Zoom.

These projects and many more were part of The Resiliency Challenge, a nine-week virtual hackathon organized by the entrepreneur incubator program BU Spark! under the hashtag #HackCOVID19. The goal, according to the challenge website: “Catalyzing student innovation in response to the unprecedented situation facing colleges and communities in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.” The bonus: feeling useful in a situation that has left many feeling powerless to address the crisis.

The event, which began in April and ended in early June, drew more than 90 projects from BU students and many others over three separate development “sprints,” all conducted remotely due to the pandemic.

“One of the amazing things about computer scientists, no matter what level you’re at, is that you have skills other people don’t have, and we also have a culture of doing, of acting, and of rapid prototyping,” says Ziba Cranmer, BU Spark! director; BU Spark! is now under the BU Faculty of Computing & Data Sciences. “That’s what hackathons are all about, building things quickly and being useful.”

Early in the COVID-19 crisis, Cranmer was “hearing from a lot of folks in the city trying to make sense of the data, whether it was a city councilor trying to get info out to their community, or whatever.” It seemed logical to put up the bat signal for hackers who could apply their capabilities to the new problems so many were facing.

Most hackathons are 24 hours or a weekend long. But between having real problems to solve on one hand, and the difficulties of quarantine and remote collaboration on the other, organizers decided to stretch it out.

The hackathon was opened up to BU students, students from other schools, and even nonstudents at the suggestion of student Spark! employees, Cranmer says, attracting entrants from all over the world, in part with the help of other schools that, like BU, are members of the Public Interest Technology University Network.

It felt good to make an active effort to combat what was going on instead of just hearing about it and saying, ‘Oh, that’s awful,’ and moving on.

Gianluca Stringhini, a College of Engineering assistant professor of electrical & computer engineering, originally suggested a project that would look at xenophobia under COVID-19. “In the early days of the pandemic, especially before it hit America, we were seeing a lot of xenophobia, people saying pretty insensitive things to Chinese members of our community,” Cranmer says.

The problem resonated in various ways with the students who jumped in and developed different iterations of the project. In the final sprint, teammates Ian Saucy (CAS’21), Rachael Dier (COM’20), and five non-BU students produced Project CRANE (Crisis Racism and Narrative Evaluation). The goal: monitoring real-time sinophobic rhetoric on Twitter—racism targeting the Chinese because the coronavirus is believed to have begun there.

“I’ve seen how, especially in the beginning, around March, there was a big difference in how COVID affected me and how it affected a lot of my classmates who are international students,” says Dier, a graduate student in emerging media. “While I was worried about a virus, they were worried about people, people were much more of a threat to them. That didn’t seem fair at all to me.”

Combing through Twitter and seeing the slurs and other language people used was disheartening and at times jarring, in part because the people tweeting the slurs didn’t all fit the stereotype of bigots, Dier says. “This research really showed it is rampant everywhere. It sheds a light that this isn’t just a southern problem, this isn’t a certain area’s problem, this is all over the United States, all over the world, people of all different jobs and all different calibers are spreading these things. That was hard to see, but it was important to see.”

“I was surprised by the amount and what it really looked like,” says Saucy, a computer science student looking to make a tangible impact on the world around him. “I’ve never had to deal with racism or hate speech. I didn’t have any idea what people might be experiencing. And to see that for real in a tweet somebody sent or that was retweeted multiple times made me more aware than I was before.”

The other Project CRANE team members were students Emma Barme of the Center for Research and Interdisciplinarity and Université de Paris, in France, Kelly Ly of UMass Lowell, and Camelia Betancourt of Iowa State University, along with design professionals Lina Hayek and Svetlana Moldavskaya. The seven had a complex task in building algorithms to define, find, identify, and map that form of hate speech, obvious or subtle. Their CRANE web app displays their data in easy-to-grasp visualizations and serves to raise awareness of how the pandemic has influenced hate speech. The app took third place overall in the hackathon.

By providing hours of work to lose himself in every day, while at the same time offering a chance to make an impact, Saucy says, “it turned out to be super-helpful for my everyday mental health.”

“It felt good to make an active effort to combat what was going on instead of just hearing about it and saying, ‘Oh, that’s awful,’ and moving on,” Dier says.

“They were an amazing group to witness,” says Cranmer. “And as the killing of George Floyd just raised the sensitivity about racism, I think the tools they are building are going to have a wider application.”

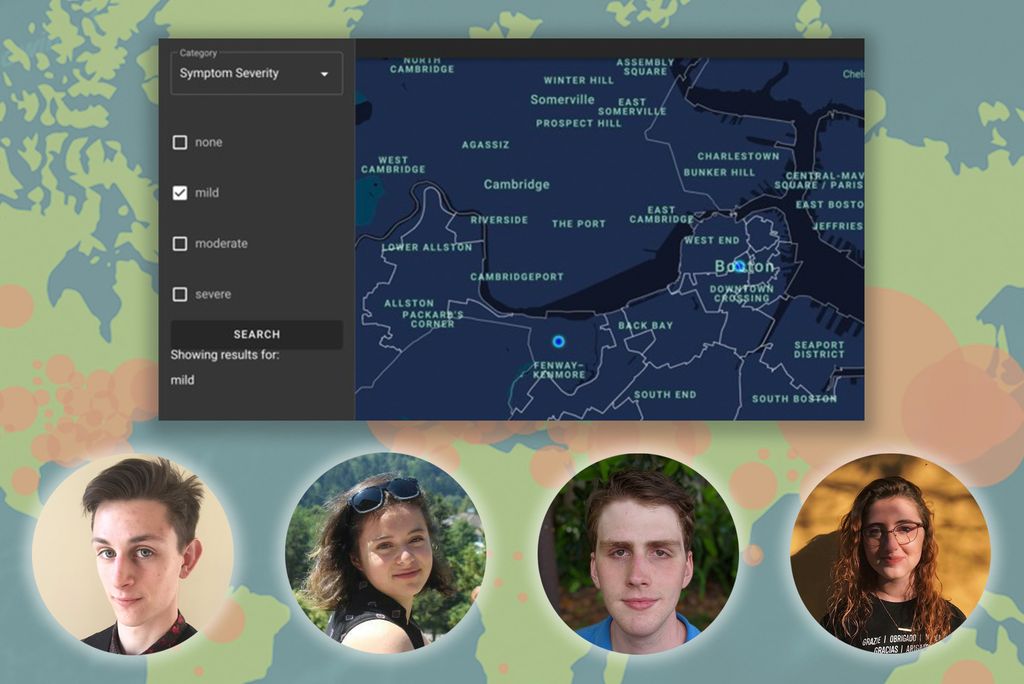

The Symptom Chatbot group consisted of Sheila Jimenez Morejon (CAS’22), Jessica Weber (Sargent’22, Pardee’22), Frank Pacini (CAS’23), and Guthrie Kuckes (Pardee’22). Their project brings symptom Q&As and case mapping to low-resource areas of Boston, finding immigrant communities via various texting apps, communities that might have otherwise flown below health officials’ radar, and it reaches the users in their own languages. It evolved from a census-outreach challenge by the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, and took an honorable mention in the third sprint.

“Basically I noticed that there were a lot of COVID-19 symptom tracking apps out there,” says Weber. “But the issue with that is, people living in poverty, and especially immigrants and refugees and elderly people, are much less likely to have smartphones they can use, so I thought it might be interesting to use SMS [text] messaging services. So often in data collection, the most marginalized communities are ignored, so we wanted to focus on that.”

What’s the pitch to users? “It has information available in your language, it’s easily accessible without an internet connection, it’s super-easy to use,” Kuckes says. “You just get the number, text it, and it will walk you through a questionnaire assessing your symptoms. It will tell you if you should get a test, if you should go to a doctor. It will give you a little peace of mind, and if the user consents to give their information, it would help figure out which neighborhoods are being hit hardest, in order to make decisions about where resources should be allocated.”

While the chatbot has not been widely deployed, it offers a route for reaching underserved populations and locating overlooked COVID-19 hotspots.

“It’s an example of how computer students have the skills to work on something and get a prototype quickly that could really make an impact,” Cranmer says. “It doesn’t have to be overdesigned or overdeveloped, it’s just—how do you get in touch with people quickly?”

BU students whose projects were among the 10 winners have been offered stipends to keep their work going this summer, while non-BU winners received Visa gift cards that could be used for continued work or be donated to a charity of their choice.

A lot of students in the hackathon were seniors, “and it just amazes me,” Cranmer says. “They had no small amount of work and probably no small amount of disappointment at the way the year was finished, and yet they’re giving back and producing something of real value.”

“I definitely felt empowered working on the project, doing something to try to help the situation in our area,” Kuckes says.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.