From the Great Boston Fire to the Depression to Coronavirus: A Short History of BU’s Biggest Campus Disruptions

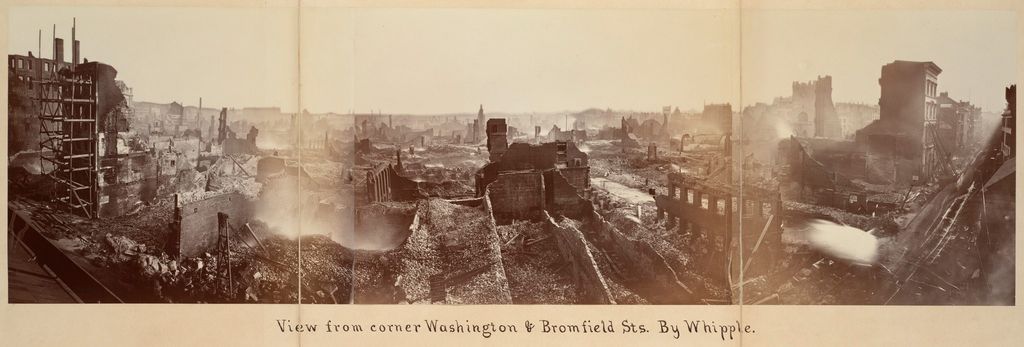

Federal Street Post Office in the wake of the Great Boston Fire of 1872. Photo courtesy of Monovisions

From the Great Boston Fire to the Depression to Coronavirus: A Short History of BU’s Biggest Campus Disruptions

In the beginning, Boston University had it all—a thriving new home in a bustling metropolis, the visionary leadership of its first president, William Fairfield Warren, and thanks to one of its founders, Isaac Rich, an immense $1.5 million bequest that made it one of the most well-endowed higher education institutions in the country.

Its academic nucleus included schools of theology, law, music, and medicine as well as new land for a campus atop Aspinwall Hill in Brookline. And BU had a bold mission: to make its education accessible to all people, regardless of race, class, gender, or creed.

But it all nearly ended on Saturday evening, November 9, 1872, when the Great Boston Fire consumed much of downtown Boston, including the Isaac Rich fortune that consisted almost entirely of real estate in the Financial District. The Brookline campus was sold to keep the University afloat, and for more than 100 years, BU struggled to find its financial footing.

From the Great Boston Fire to the current coronavirus pandemic, BU has experienced its share of major disruptions. But from the somber losses of each story emerged periods of persistence and triumph. The ashes of the Great Boston Fire soon gave way to the establishment of the College of Liberal Arts (now the College of Arts & Sciences) in 1873 and the School of All Sciences (now the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences) in 1874.

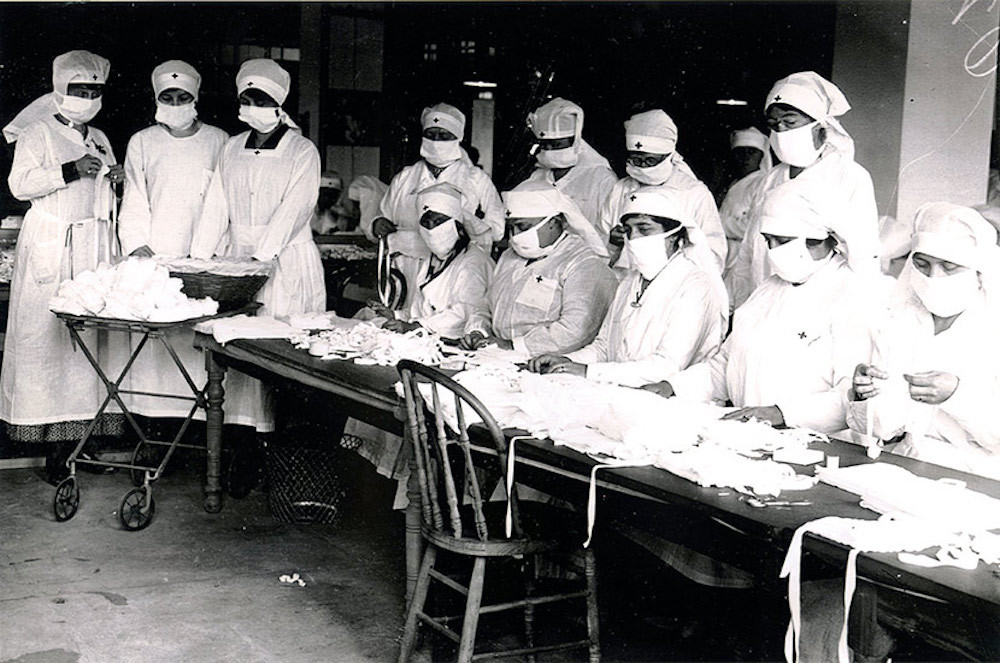

1918

Many have likened today’s coronavirus pandemic to that of the 1918 flu pandemic, which hit BU at the same moment it was training military officers for World War I. Registration was postponed three times that fall, and faculty resorted to sending reading assignments by postal mail. Classes finally began in late October on an abbreviated nine-week schedule, with early morning meetings, mess halls, and hundreds of students in army uniforms. After the pandemic, the University took advantage of burgeoning enrollments, and with much foresight, purchased 15 acres of land between the Charles River and Commonwealth Avenue for a future campus.

1929

Until this point, BU had survived fire, war, and a flu pandemic, but the Great Depression was almost too much. It dragged on cruelly for almost a decade, dropping enrollments by 35 percent and contributing to the largest deficit in University history. Salaries were cut, layoffs were implemented, and the Board of Trustees even tried to sell the land along the Charles River. Luckily for us, they were unsuccessful.

After many cumulative years of fiscal frustrations, Daniel L. Marsh (STH’08, Hon.’53), BU’s fourth president, nailed down the University’s commitment to the Charles River Campus. Up to this time, University buildings and units were scattered all over the region, from Beacon Hill to Copley Square to Cambridge to the South End, and even to Weston, site of BU’s athletic fields. But on the eve of the 1938 Commencement, Marsh obtained a $586,000 donation that assured construction of the University’s first building on the new campus. The Great Depression had finally ended for BU.

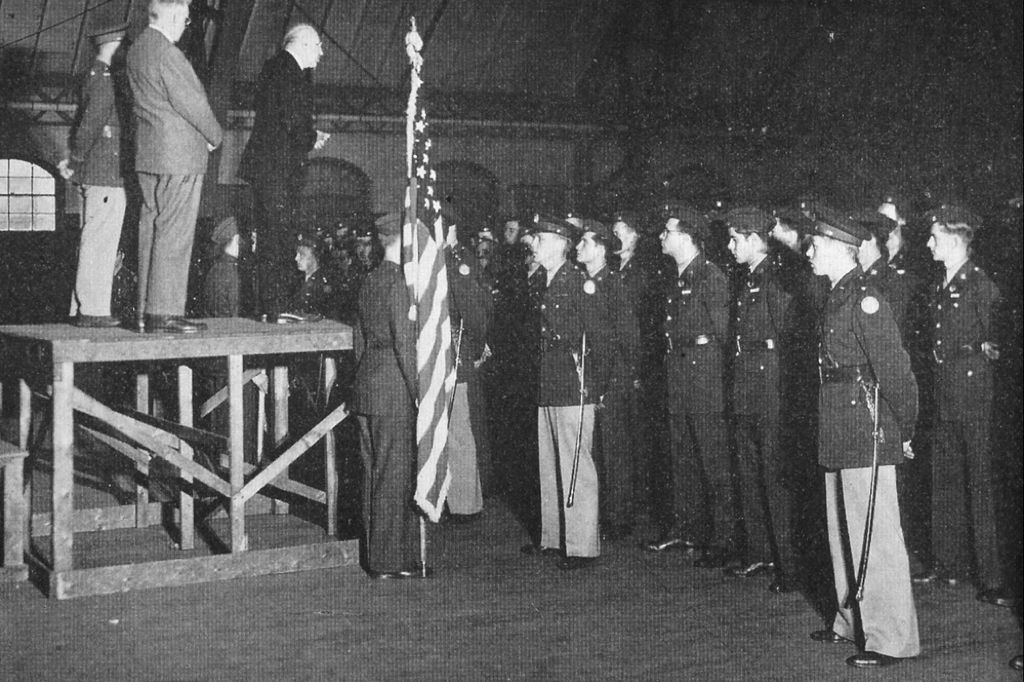

1939

In September 1939, eager students flocked to the steps leading to the College of Business Administration (now Questrom School of Business) brand-new Charles Hayden Memorial Building at 685 Commonwealth Ave. The University community was ecstatic and hungered for more construction. It was not yet to be. Nazi Germany invaded Poland that same month, and World War II forestalled all new construction for nearly a decade.

After four straight post-Depression years of growth, BU enrollments plummeted by 14 percent from 1941 to 1942. In keeping with the nation’s war effort, the University implemented an accelerated academic calendar, with undergrads completing their degrees in just three years. Marsh later insisted that students of Japanese heritage be admitted to BU after their disgraceful internment on the Pacific coast during the war, and the University openly welcomed Jewish students, while neighboring colleges applied surreptitious quotas on Jewish applicants. When the deadliest conflict in human history ended in 1945, a total of 8,253 BU alumni and students had served their country and 202 had paid with their lives.

1970

By 1970, the United States had escalated its forays in the Vietnam War, invading Cambodia and provoking ever more protests across the nation. The University experienced building evacuations, violent protests, and daily bomb scares. In the wake of the Kent State University shootings, the 1970 University Commencement was canceled (a heartbreaking decision that would not happen again until this year). Those graduates were invited to return to campus forty years after missing out on their moment to finally take part in a well-earned academic procession at BU’s 2010 Commencement.

Amid the current coronavirus crisis, a grave weight of uncertainty burdens many in the University community who are attempting to learn, teach, and work amid this new normal. But perhaps there is a lesson of hope in this history. As President Marsh said in 1933, “the Depression may baffle us for a while, but it cannot beat us.”

For those interested in reading more about these and other events in the history of Boston University, see the institutional histories this article is based on: Warren O. Ault’s Boston University: The College of Liberal Arts, 1873-1973 (1973), Kathleen Kilgore’s Transformations: A History of Boston University (1991), and 70 Stories about Boston University, 1923-1993: A Memoir (1999), by George Makechnie (Wheelock’29,’31, Hon.’79).

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.