BU Engineers Are Taking on the Coronavirus Pandemic

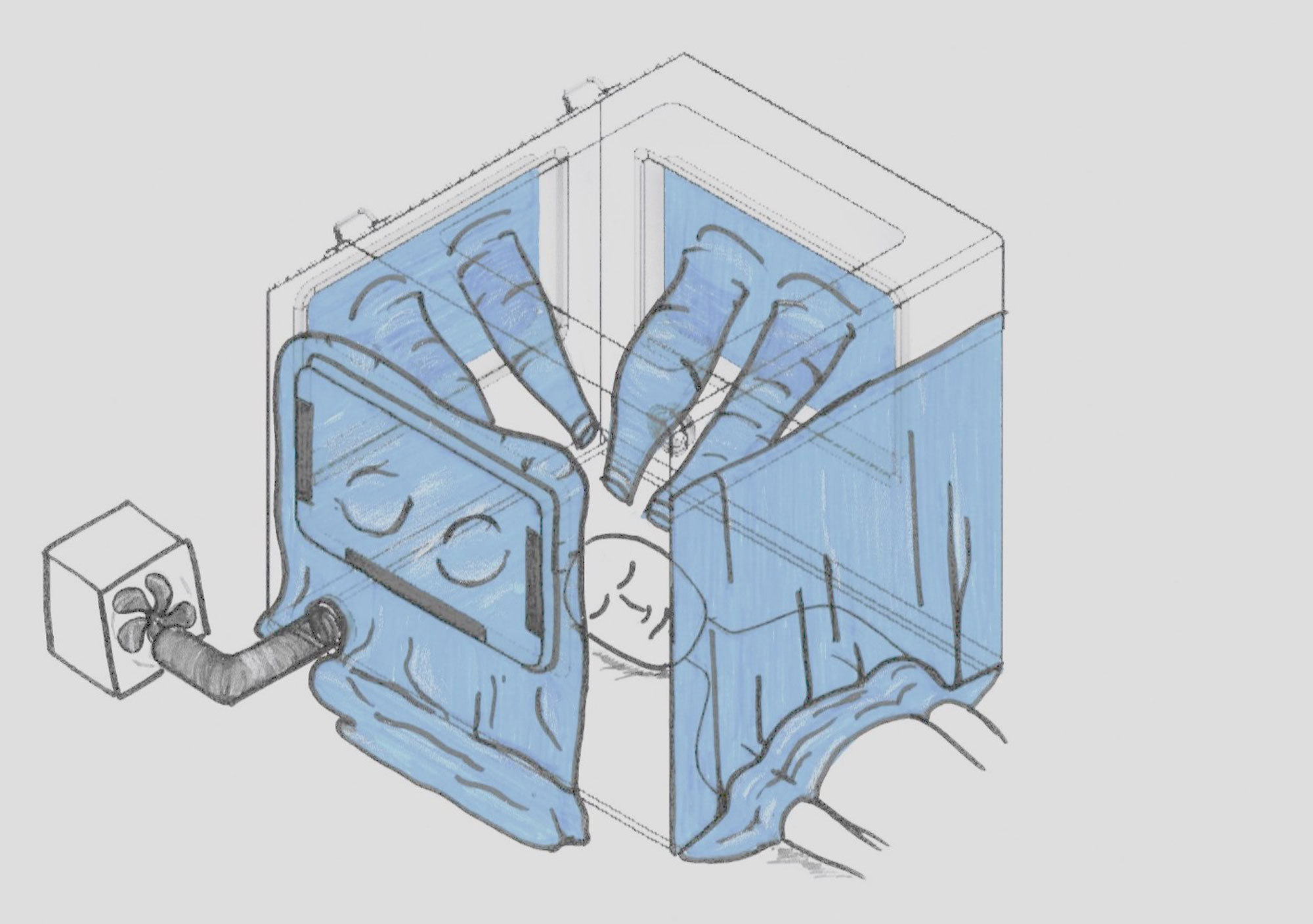

Among other projects, BU engineers are collaborating with clinicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center to develop a respiratory isolation box, sketched here. Courtesy of Joyce Wong

BU Engineers Are Taking on the Coronavirus Pandemic

Researchers are mobilizing to develop better, faster COVID-19 testing and improved medical equipment

Across Boston University’s School of Engineering, researchers are pivoting their work to tackle the many engineering problems associated with the global coronavirus pandemic.

“I’m glad I’m an engineer right now,” says Joyce Wong, a professor of biomedical and materials science engineering. “There are so many problems that need to be solved in this crisis and I can actually use my expertise to help.”

Wong, like many other engineers and researchers, is diving in to do what she can to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. These efforts are in addition to the first wave of help, across BU’s Charles River and Medical Campuses, that gathered personal protective equipment (PPE) from labs—shuttered by Governor Charlie Baker’s stay-at-home advisory—to donate to healthcare workers in Massachusetts. Here are four ways that BU engineers are using technology to tackle the coronavirus pandemic:

1. New medical equipment

Wong started working on two projects after talking to her cousin, Steven Horng, an emergency medicine physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC).

“I started hearing about the PPE shortages from Steven, and then he started to tell me about more of the challenges healthcare workers are facing,” she says. “We’re getting close to the predicted peak of cases in Massachusetts, so I want to help out any way I can.”

Wong is now collaborating with BU engineers Enrique Gutierrez Wing and J. Gregory McDaniel on medical equipment designed to help contain the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for causing COVID-19 infections.

The first device is inspired by a photo Horng saw of an intubation box built by a Taiwanese doctor. Together, Horng and Wong teamed up with Gutierrez Wing and McDaniel to expand on that idea and make a negative pressure chamber, meant to safely isolate patients sickened by the virus and prevent their respiratory droplets from dissipating in the air outside the chamber. They also enlisted the help of Emily Whiting, a BU computer scientist and art technologist, and Patricia Fabian, a BU environmental health expert and infectious disease systems scientist.

The team has designed their so-called “respiratory isolation box” with features to allow doctors to maintain the same standard of care, but with an added layer of protection. In addition to being a negative pressure chamber—meaning air doesn’t escape the box, but can flow in—it’s also designed so that up to three clinicians can work on one patient at a time. And the team is testing the box’s internal dimensions to make sure healthcare workers can still use the specialized equipment they may need when intubating a COVID-19 patient. The box is in the prototyping phase, but the team is collaborating with clinicians at BIDMC and planning to test the prototype in a medical simulation lab.

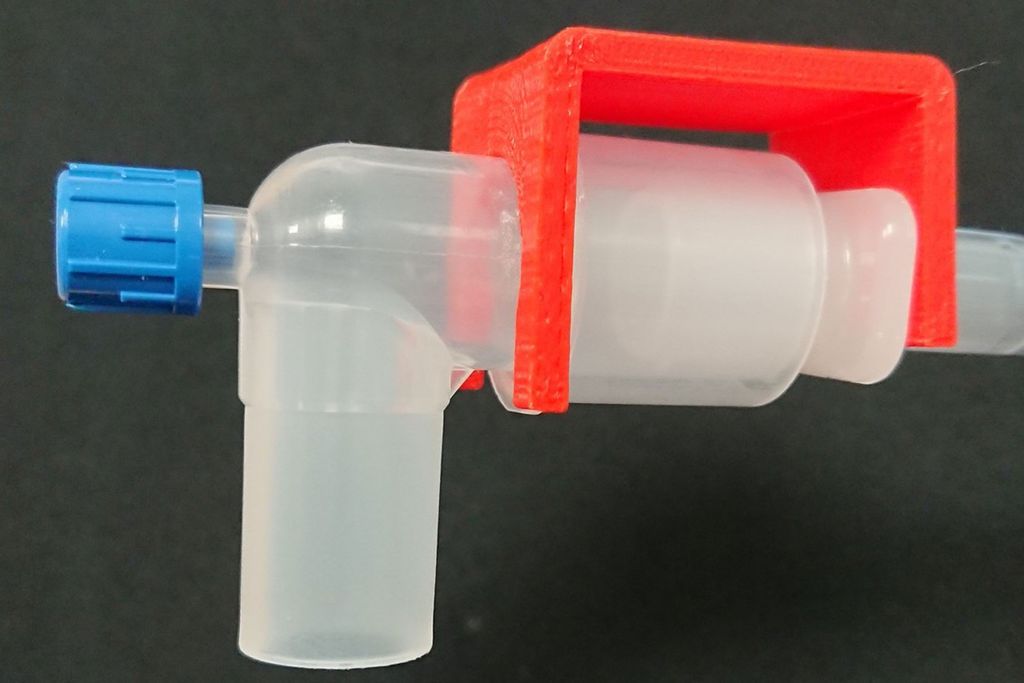

The second medical device that Wong, Gutierrez-Wing, and McDaniel are developing is a 3D-printed bracket designed to hold together an endotracheal tube and the respirator circuit it’s attached to. In normal use, these connections between the ventilator machine and the tube that’s inserted down the patient’s throat are loose, intentionally made so that they can easily be disconnected in case the patient needs to be suddenly moved in an emergency situation. Sometimes, however, the loose connection comes apart randomly, disrupting ventilating and triggering an alarm that sends clinicians scrambling to reconnect it.

But in the case of patients receiving respiratory support due to COVID-19, when that disconnection happens, the air coming out of the tube and into the room is full of droplets containing the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leaving others at unnecessarily high risk of exposure and infection. In contrast, the bracket that Wong’s team is developing easily clips into place to hold the tube and respirator hookup together to prevent this from happening. The 3D-printed bracket is made of a material that can be easily sterilized, and the prototype is designed with rounded edges so that it won’t tear clinicians’ latex gloves (which are now in especially short supply).

2. A novel (and more rapid) COVID-19 test

Selim Ünlü, a BU professor of electrical, computer, materials science, and biomedical engineering, is teaming up with longtime collaborator John Connor, a BU School of Medicine associate professor of microbiology, from the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories. Together with Mehmet Toner of Massachusetts General Hospital, the trio is working to develop a rapid and reliable test for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The currently available tests look for the presence of SARS-CoV-2’s viral RNA, a unique and identifying genetic code. Building on his previous research, Ünlü’s test is fundamentally different: it detects and counts individual SARS-CoV-2 viruses by capturing them with antibodies.

The primary benefit of this approach is that its testing mechanism doesn’t require extensive sample preparation. It also reduces the chance of false negative results. Viruses can mutate, but the currently available tests rely on knowing specific genetic sequences of the virus to detect it. So, if the coronavirus mutates within one of those sequences, a current test could report a false negative—which happened during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, making it difficult to accurately diagnose who was sick and contain the outbreak.

Ünlü also says that his test uses a different set of supplies than the existing test, leaving it less prone to supply chain shortages than the current method.

3. Speeding up test validation

Catherine Klapperich, director of the BU Precision Diagnostics Center and a professor of biomedical and materials science engineering, is spearheading a team to validate new types of SARS-CoV-2 tests. To contain the current COVID-19 pandemic, and prevent future relapses, an extreme ramp-up of testing is needed across the United States. But there are currently roadblocks and shortages of supplies barring that from being possible. To increase testing capabilities, new tests, like Ünlü’s, must be evaluated and validated through FDA regulatory procedures. Those validations take time—so, Klapperich’s team is trying to speed up that process.

The Precision Diagnostics Center is taking on the task of preclinical lab validation of newly developed COVID-19 tests. First up, they’re working with one developed by Michael Springer’s systems biology group at Harvard Medical School.

Klapperich’s team has already validated a version of his test by seeing how well the method can be used to positively detect flu from a bank of H1N1 patient samples from the 2009-2010 pandemic. Now with that proof of concept in hand, Springer is adapting the test to make it work for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In the meantime, Klapperich is securing COVID-19 patient samples from collaborators at Boston Children’s Hospital to validate the next iteration of Springer’s assay as well as COVID-19 tests developed by other research groups.

4. Improving nasal swabs

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the supply chain for the nasopharyngeal swabs used to collect patient samples for testing has not been able to keep up with demand. Seeking to find an alternative, pathologist Joel Henderson of BU’s School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center (BMC) reached out to BU’s College of Engineering for help. Jessie Song, a graduate student pursuing a PhD in biomedical engineering, answered the call.

Song, who does research with BU engineering faculty members Alice White and Mark Grinstaff, is an expert at using nanoscale 3D printing to create tissue scaffolds. She immediately saw the potential of using 3D printing to fabricate nasopharyngeal swabs. Working from prototype designs of nasopharyngeal swabs from the University of South Florida and Northwell Health in New York, Song selected a safe and sterilizable resin—often used to fabricate FDA-approved dental medical devices—and assembled the tools necessary to make several different prototypes. Within one week of receiving Henderson’s call for help, the first batch of nasopharyngeal swabs was printed overnight at BU’s Multiscale Laser Lithography laboratory.

“Jessie is a prime example of what makes BU a great place—it is the students,” Grinstaff says.

Henderson and his team are now evaluating the swabs Song fabricated to decide which designs they prefer and why, as well as how best to sterilize and package the swabs into kits.

Not only would this 3D printing approach, using new materials, skirt the supply chain issue that prompted Henderson’s call for help, it could also reduce the likelihood of false negative COVID-19 test results. Nasal swabs used for coronavirus tests must be pushed up a patient’s nose to collect a mucus sample from where the throat meets the back of the nose, which requires training and can be prone to user error. A swab made of a material that more easily collects mucus, increasing the chance of capturing a high-quality sample, would help reduce false negatives, the researchers say. Once an optimal swab design is identified, the team plans to conduct a clinical trial at BMC.

Story adapted for The Brink by Kat J. McAlpine.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.