Giving Gone Bad

CAS prof, colleagues study how corporations disguise lobbying as philanthropy

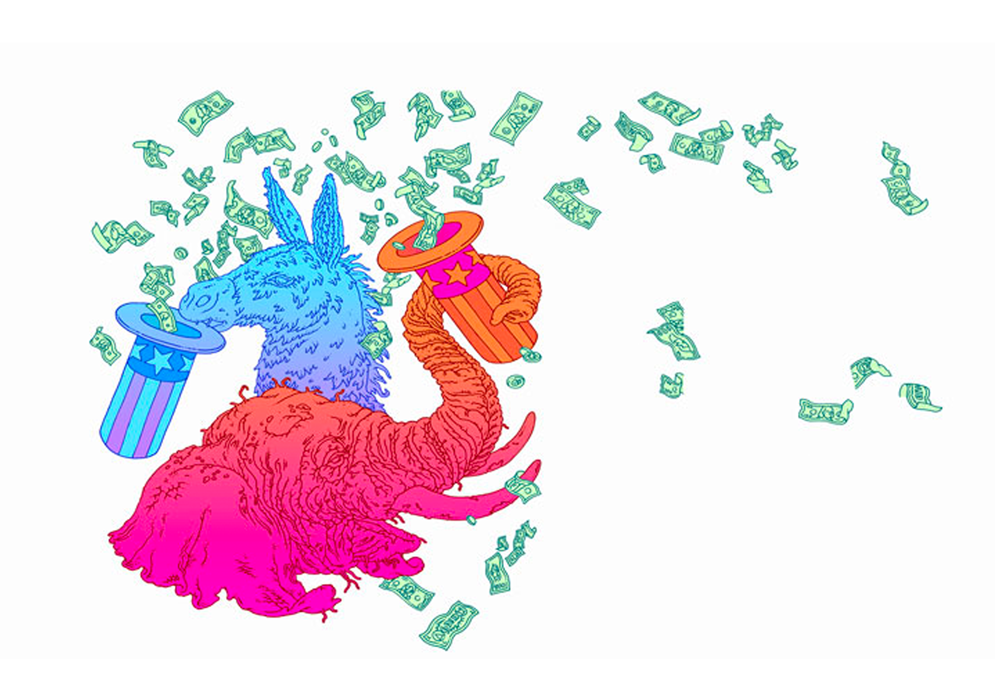

Corporations have been spending money, tax free, to influence politicians. We had no idea. Illustrations by Eric Nyquist

What’s wrong with this scenario?

In 2014, a charitable foundation established by the agriculture company Monsanto gave $1,350 to a nonprofit arm of the University of Northern Iowa, whose trustees included Iowa Republican Senator Charles Grassley. Monsanto was one of 11 corporate foundations that gave to charities with ties to Grassley.

This sounds like a win-win-win. A senator volunteers for charities. Corporate foundations give to those charities. The charities help those in need. But corporate philanthropy is not as straightforward—or as philanthropic—as it might seem, says BU College of Arts & Sciences ecomomist Raymond Fisman.

In their 2018 study “Tax-Exempt Lobbying: Corporate Philanthropy as a Tool for Political Influence” (circulated as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper), Fisman and three colleagues investigated the business-oriented motivations of philanthropic foundations established by companies. They looked specifically at Fortune 500 and S&P 500 corporations and discovered that their foundations have been donating to politicians’ pet charities.

Their evidence: when a member of Congress joins a committee that makes decisions on policies important to a corporation in their district, charitable donations to nonprofits headquartered in that district increase. And when a politician leaves Congress, charitable giving into their district declines.

“Our analysis suggests that firms deploy their charitable foundations as a form of tax-exempt influence seeking,” the researchers write; they estimate that “7.1 percent of total US corporate charitable giving is politically motivated…. Given the lack of formal electoral or regulatory disclosure requirements, charitable giving may be a form of political influence that goes mostly undetected by voters and shareholders, and which is directly subsidized by taxpayers.”

In effect, corporations have been spending money, tax free, to influence politicians—and we had no idea.

Cardboard Checks

Fisman’s research on corporate charitable donations began with a conversation. A former student who’d taken a job at a large corporation observed that the firm’s government relations team seemed to have a strong hand in its foundation’s giving decisions.

“They were in the business of handing out oversized cardboard checks to charities that would be appealing for whatever set of reasons to legislators that mattered to the company rather than thinking about the social purpose of the foundation,” says Fisman, Slater Family Professor in Behavioral Economics. “I have gone back to that conversation many times over the years. It really stuck with me.” In his research, Fisman followed up on his student’s observation that there were clear ties between corporate giving and its political interests. “You can think about this paper as a formal test of that proposition,” he says.

Before Fisman started digging, no one had looked systematically into charitable giving as a form of political lobbying; there’s no central clearinghouse of data that shows what charities members of Congress are actively involved in and who donates to them. In fact, the information connecting donors to their donations is so hard to find that it took Fisman and his colleagues from the University of Chicago and the University of British Columbia several years of detective work.

They assembled tax returns filed by the foundations, which list charitable donations. They examined corporate lobbying records that indicate which issues a company cares about. They tracked Congressional committee assignments during these years. They studied the personal financial disclosure forms filed by members of Congress, which require them to list some (not all) positions held with nongovernmental organizations such as nonprofits. In all, they combed through 17 years’ worth of data hunting for correlations among corporate charity reports by philanthropic foundations and the charitable affiliations of members of Congress.

The researchers identified contributions to 1,087 nonprofits linked to 451 members of Congress between 1998 and 2015. Based on foundations’ contributions in the 2014 campaign cycle, the researchers estimated that 7.1 percent of total US charitable giving—amounting to $1.3 billion—is politically motivated. That’s 280 percent more than all political action committees raised and spent in the same period. Imagine how much influence that could buy.

While Fisman’s research seems to draw a clear line between charitable contributions and members of Congress, his paper does not prove that the money has influenced the politicians’ decision-making.

You give someone a little gift and you get something from the goodwill in return.

— RAYMOND FISMAN

“That’s a really fundamental problem with money in politics,” says Maxwell Palmer, a CAS assistant professor of political science and a junior faculty fellow at the Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering. “Let’s say I’m a member of Congress and a company helps raise money for my campaign; then, later when I get elected to Congress, I vote in line with what that company wants. How can you tell if my vote was bought or influenced by that company, or if that company supported me because they knew I already agreed with them? We really can’t get at that actual direct effect of contributions.”

That said, Fisman’s finding that charitable donations fluctuate depending on whether a politician holds a certain congressional appointment suggests that corporations “clearly think what they’re doing makes a difference,” Palmer says. “And so maybe we should, too. It’s a ‘where there’s smoke, there’s fire’ sort of thing.”

King Louis XVI’s SnuffBox

Our Constitution maintains that every citizen should have the same size megaphone to make their voice heard on issues that come before elected leaders. Fisman’s research shows that politically motivated contributions could be a way for corporations to buy a louder megaphone—and make taxpayers fund it.

While there are limits on campaign contributions, no such restrictions apply to charitable giving, which is tax-deductible to encourage greater beneficence. But Fisman wonders if corporate foundations should be afforded the same tax break—which, after all, comes at the expense of government coffers—when those donations are to politicians’ pet organizations. By contrast, the money companies use for paying lobbyists to express their concerns on Capitol Hill is not tax-deductible.

“We’ve decided that lobbying shouldn’t lower my tax bill. So, that’s the sense in which a politically motivated charitable donation advantages the voice of corporations,” says Fisman, who’s started a new project examining whether it’s better to prevent companies from misbehaving or provide incentives for acting positively.

And if you doubt that gifts to public servants matter, the Founding Fathers had a different view. They included a clause in the Constitution stating that Congress has to approve presents “of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.” That clause is why Benjamin Franklin, on his return from a diplomatic term in Paris in 1785, had to get permission to accept a diamond-encrusted snuffbox gifted to him by King Louis XVI of France.

That famous story characterizes the problem: a gift creates a sense of indebtedness. “Salespeople have exploited this weakness from time immemorial,” Fisman says. “You give someone a little gift and you get something from the goodwill in return.” And that’s not great for democracy.

Palmer adds, “We might worry as citizens that our representatives hear companies speak louder and have their views expressed more directly in ways that we can’t see, rather than listening to their constituents.”

But what can we do about it? Fisman says he’s a strong advocate of old-fashioned calls to Congress. Voicing one’s opinion as a citizen, at every opportunity, is a proven way to be heard. Voting is another.

On a systemic level, Fisman says, he would favor a law that makes donations to charities with Congressional ties public, like individuals’ contributions to candidates.

“I’m not a ‘the truth will set you free’ type of person,” says Fisman, the author of Corruption: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2017), “but I do happen to think that making these things transparent can be a big, big step in the right direction.” It’s not a cure-all, however.

“Our broader point is that this is one channel, one hidden channel, by which companies influence politicians,” he says. “We’re certainly not saying it’s the only one. The point is that there is an array of hidden channels that are potentially as big as the ones that we observe easily and over which there is already a great deal of hand-wringing. The hand-wringing about lobbying is just because we see it. It’s that stuff that we don’t see that troubles us more.”

Michael S. Goldberg can be reached at goldmich@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.