Taking His Time

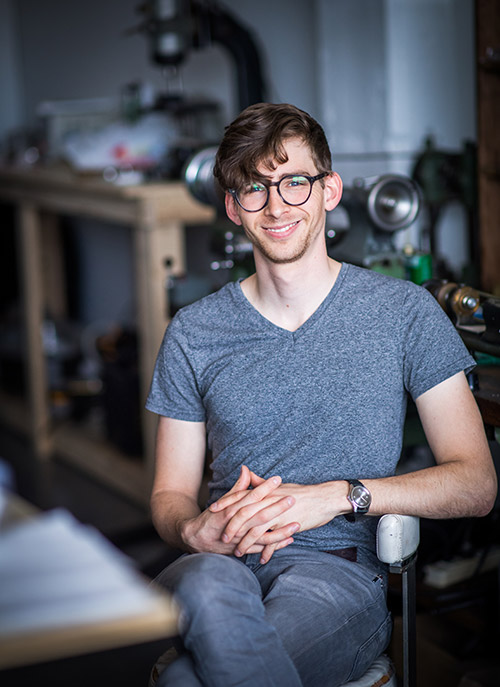

Ian Schon (ENG’12) makes analog watches in a digital world

Ian Schon (ENG’12) hunches over his workbench in his Allston studio holding the tiny hour hand of a wristwatch with tweezers.

Shaping the delicate part, just a fraction of a millimeter wide, takes hours of painstaking labor. And the sliver of stainless steel is just one small piece of a mechanical watch that will take 100 hours of finger-aching work before the finished product can be worn on someone’s wrist.

Fortunately, Schon’s in no rush. In fact, he seems to relish the tediousness of the job, transfixed for hours as he buffs the face of a watch or refurbishes the movement.

“I take my sweet time,” he says.

A young watchmaker is a rarity in this era where iWatches offer up-to-the-minute headlines, text messages, and heart rate information with the flick of the wrist. For every 10 watch repairmen retiring in the US, just one enters the business, according to the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute, an industry group. And the institute doesn’t even track the number of people who actually practice the ancient craft of making watches in the US because they are so few and far between.

But Schon, just 28, is from another time zone, a millennial clinging to an analog tradition the way some people still collect vinyl records or ride fixed-gear bicycles. His one-man company, Schon Horology, which he launched earlier this year, creates old-fashioned, wind-up wrist watches. They are not powered by quartz, they do not offer a calendar or a chronograph, and they perform one function: telling time. They also sell for $5,200 each.

A former corporate product designer, Schon says he has already sold a dozen of his unique creations this year by word of mouth alone.

“I think in business school, they use watchmaking as a case study to talk about what not to do, what industry not to enter,” says Schon (pronounced like “loan”). “I believe there is space for people who are willing to do watchmaking differently. And if you’re willing to do it differently, people will take notice.”

He began tinkering with watches in 2013, after purchasing a watch online that was not as advertised. He took it apart and decided to use the metalworking and machining skills he had developed as a mechanical engineering student at BU to build a new case for it.

He soon started making other parts too, and found that he was hooked, spending hours lost in his newfound hobby.

While he would engineer sound systems and medical devices by day, at night he made watch parts in his Brookline apartment, slowly acquiring the highly specialized tools he needed, like vintage lathes from the 1940s and drill bits to make holes no wider than an eyelash.

But turning his new hobby into a small business required help. Watchmaking can be a very closed, even secretive business, and Schon needed a mentor. He sought out Nicholas P. Trahadias II, a Swiss-trained high-end men’s watch repair specialist who works in Downtown Crossing in Boston’s Jewelers Building.

Trahadias says he will never forget the day Schon arrived at his office by bike and showed him his work.

“Ian brought product in and showed me what he had done,” says Trahadias, recalling how surprised he was by the quality of Schon’s work. “The minute he did, I knew he would be able to meet his objectives.”

The arcane world of watchmaking terminology can also be confusing. Trahadias is a watchmaker, an industry term describing a person who repairs and refurbishes watches. Schon, who makes watches, is a horologist, which is “quite rare,” Trahadias says.

Schon has met with Trahadias and worked at his side for the last five years. “Each time I described or explained something, you could see the gears moving in his head,” he says of Schon. “You could see his mind working.

Schon’s pens, which cost as much as $188 each, are sold throughout the world.

Schon says he has long been fascinated by tactile objects, whether the look and feel of a watch, a pen, or the frame of a bike. As a student at BU, he designed and manufactured a line of aluminum pens and raised nearly $70,000 on Kickstarter to finish and sell them in stores for $55 each.

That venture, called Schon DSGN, took off. His pens now fetch as much as $188 each and are sold in boutiques around the world. Feeling burnt-out in his full-time job, and making enough income from his pen business, Schon left his job as a product designer last year to devote himself to making pens and watches.

“I wanted people to appreciate me for what I can do,” he says. “Not just what I can do for them.”

Wearing old Sambas, his curly hair reminiscent of 1990s’ Lyle Lovett, Schon displays some of the elements from his current watch collection, The Dot, a reference to the hole in the watch face above the numeral 6 where a dot circles into view every 10 seconds to let the owner know the watch is keeping time. (There is no second hand.)

The watch contains expensive NOS Doxa Swiss-made movement, which Schon says he has obtained through industry connections, declining to elaborate. (Remember, this can be a secretive business.) He refurbishes the movement, the watch’s engine. He also designs and manufactures the face, hands, and case, which are machined in Massachusetts and then finished in excruciating detail at his studio workbench.

A single day can be spent on the watch bezel, the grooved ring holding the glass cover of the watch’s face. Or Schon will spend hours trying to get the hour hand to a specific thickness and weight so that it “presses on exactly correctly” to the watch’s movement.

“It’s physical, and emotionally exhausting,” Schon says. “You’re spending so much energy making sure it’s right and as you do it, the risk keeps going up that you might ruin it. You get a scratch or over-polish it and you have to start over. It’s painful.”

Mike Stone (ENG’12), Schon’s friend since their undergraduate days in the mechanical engineering program, says the intensity of the work suits Schon, a type who will leave “no conceptual stone unturned” in a project.

“I joke that the watch is the ultimate engineer nerd object, and Ian embodies that archetype,” Stone says. “His attention span seems infinite in a particular direction.”

Time at the Bench

Schon’s Allston workroom, in a building occupied mostly by artists, overlooks the Mass Pike. It’s quiet, except for the white noise from the traffic outside, and surprisingly dimly lit.

He is readying a shipment of pens before he goes to work on a watch face that will occupy him for the afternoon.

“Time at the bench is my favorite way to spend time,” he recently told his 943 Twitter followers.

Schon says he’s not antidigital or extremely sentimental about watchmaking, although it’s a line of work that’s fading fast. (Apple’s Tim Cook said this year that iWatch sales have outpaced the Swiss watchmaking industry’s.)

Schon wears his watches, and carries an iPhone. He also carries one of his pens and a notepad for sketching in his back pocket. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter help him get word out about his watchmaking process and prowess, but he says he is always mindful of the time he spends online, preferring the analog world.

He recently got married, and says he’s not trying to get rich or thinking about how to scale his operation to boost profits. It’s about spending his time the way he wants to spend it.

“People say I could make a hundred watches a year and slay it,” he says, “but that’s not the point.”

“I make these watches,” Schon says, “which will be a lifetime’s pursuit.”

Meg Woolhouse can be reached at megwj@bu.edu. Aaron Hwang can be reached at aahwang@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.