A Conversation with Zadie Smith

Tickets to author’s Q&A with students available today

Prize-winning author Zadie Smith will speak about her work during a breakfast with students on Tuesday, March 27. Tickets to the event are available through Eventbrite starting today. Photo by Dominique Nabokov

Zadie Smith was just 24 and fresh out of Cambridge University when her first book, White Teeth, catapulted her to fame in 2000. The satirical novel follows two families over several generations and earned Smith critical kudos and a slew of awards.

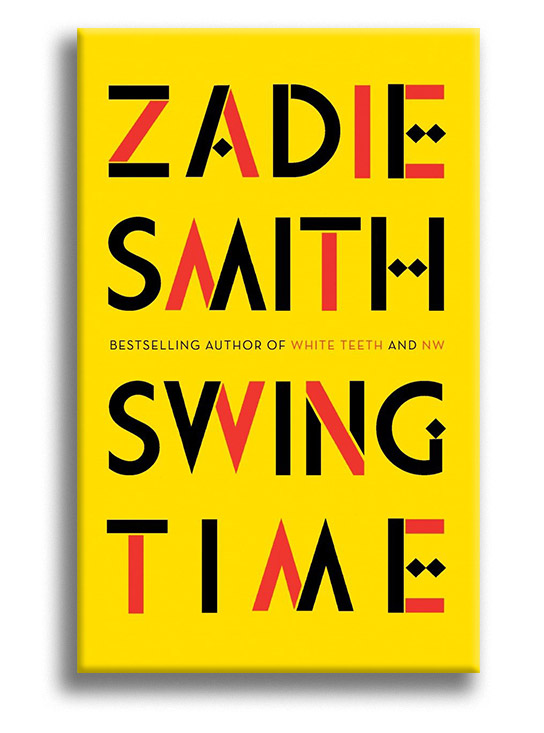

Several other novels, among them NW, On Beauty, and most recently, Swing Time, set in the author’s native England and in West Africa, cemented Smith’s reputation as one of the most original voices writing today.

In addition to writing fiction, Smith is an accomplished essayist, and her work frequently appears in the New Yorker and The New York Review of Books. The pieces in her latest collection of essays, Feel Free (Penguin, 2018), were written between 2008 and 2016 and cover topics from social media to pop culture and British politics to race relations in the United States, as well as moving portraits of her parents.

Smith, a New York University professor of creative writing, will be on campus on Monday, March 26, to speak with Christopher Lydon, host of WBUR’s Open Source, at the Tsai Performance Center. The conversation, titled On Writing, is sponsored by several BU schools and offices, and inaugurates a new speaker series, Conversations in the Arts and Ideas, highlighting the humanities at the University.

While tickets to the conversation are no longer available, Smith will meet with students for an informal Q&A over breakfast at 9 am on Tuesday, March 27, at the Photonics Center. Carrie Preston, Arvind and Chandan Nandlal Kilachand Professor and dean of Kilachand Honors College and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, will moderate. Students interested in attending can register for tickets through Eventbrite here.

All Kilachand Honors College freshmen, BU Trustee Scholars, and those enrolled in the CAS Core Curriculum have been assigned to read Swing Time. Those students and others across campus who’ve been reading the book on their own are participating in book club and other discussion groups before Smith’s conversation with Lydon and the breakfast Q&A.

“Zadie Smith writes with great urgency and understanding about growing up in a globalized world, where questions of roots, identity, and inherited or adopted cultures shape daily life,” says James Johnson, a CAS professor of history and one of the organizers of her visit. “Our students know especially vividly what’s at stake in such questions. The palpable excitement her visit has generated among them is an indication that the preoccupations of her writing are also theirs.”

BU Today spoke with Smith about writing, her move from England to the United States, and what she’s working on at the moment. Excerpts from the interview are below.

BU Today: You’re a novelist, a short story writer, and an essayist. Does one genre inform the other?

Smith: I guess one is a relief from the other. Short stories are unbelievably difficult. I really am not very good at them. I try hard, but I don’t try very often. It’s a completely separate skill. It’s very hard and I have no background in it. I maybe wrote three in my life before I published White Teeth, and none of them were very good. It’s just not something I thought about when I was younger. I thought about novels all the time. Americans are incredibly skilled in this area, so when I moved here, I realized where the bar was, which was very high.

Do you find writing a novel easier?

Yes. It’s much easier for me to expand and to think of things over many chapters. And it’s hard for me in a short story to be anything but preachy or dogmatic. It’s very hard for me to keep them open in the way they should be kept open. For me, it’s a difficult form. When I write short stories, they tend to be something more like fables. That’s the form I’m able to manage.

You’ve said writing a novel is like “embarking on a long run.” Can you expand on that idea?

When you start a very long run, you’re optimistic the first mile or two and then it becomes a bit of a slog. So I have to be quite sure in the idea of the novel. But I’m of the opinion that the idea usually comes quickly and it’s kind of unavoidable. My husband asked recently about this novel I’m trying to write, which is historical, “Are you sure you want to write this novel?” But there’s no way out once it presents itself. It’s a strange thing. It must be partly subconscious. And then your ego is submitted to this strange subconscious demand to write a particular thing.

I understand that the new novel you’re beginning is set in North London between 1830 and 1870 and is your first foray into historical fiction. Are you enjoying it?

Well, I haven’t written a word yet and probably won’t for a couple of years, but I love spending every day reading. I was talking to a friend, who wrote a historical novel, about when you should stop. You can’t read everything about the year you’re writing about. It could just go on infinitely. It really feels like being in college again, when you have a set task. For me, that was always an enjoyable thing, when you had a pile of books and you knew once you finished that pile of books that it was time to start. I respond very well to set tasks.

When you moved to the United States about nine years ago, did it change your writing?

Yes. I mean it’s under the influence of American magazines, American newspapers, American writers. There’s a prejudice towards plain speech here which is long-standing, and I see a lot of good in it. It made me a little less chintzy, if I can say that about language: it became simpler, more forthright, and that was all good. Also, I think Americans never give themselves credit for this, at least in this East Coast intellectual community we’re talking about—there is a great seriousness, which I think historically is like this Emersonian seriousness. But the funny thing about the British and the Americans is the Americans stayed serious and the British have no intention of being serious in that way. So I think here, there’s the freedom to write prose that is serious or intellectually concerned, and if you do that in England, you’re very likely to be put in what’s called “Pseud’s Corner,” which is kind of a comic column in Private Eye, where anything that’s considered over-wordy or over-intellectual winds up. So I quite enjoy the freedom of being a pseud in New York, where it’s not embarrassing to think and talk about thoughts in abstract ways or in extensive ways. That was a great freedom for me.

So the move has been liberating for you as a writer?

Yes, I think so. I think I would have been a very different writer if I’d stayed. I love England, but I needed to get out. I spent a lot of time under English aesthetics and English rules and English ideas. And it’s good to get out, it’s good to move around.

It’s been almost 20 years since White Teeth was first published. Has your writing changed over time?

It’s less funny and more austere, but I don’t think it’s a permanent change. What I’m thinking about writing now is funnier again. I think it just depends on your mood. I think the thing which changes for a young satirist, which I more or less was, is that the kind of satire in that novel is a lot of laughing at people. As you get older, it becomes a little harder to laugh at people in the same way, or at least, you become implicated. It’s so hard to understand when you’re 19 or 20 why middle-aged people are like they are or why marriages continue. You don’t understand any of it, you just wonder, what’s wrong with you people? And then, of course, you become middle-aged and go, ah, OK, I get it now.

You’re a tenured professor at New York University. When aspiring writers ask for advice, what do you tell them?

I’m not good at that. I can’t talk about writing in the abstract, and advice is not something I ever sought. The only advice I know is to read as much as you can, and they always look at me like, “Really? That’s it?” But I don’t know any other way to write. So if they’re asking for my personal experience, the only thing that I ever found useful was reading as much as possible and learning from each book I read.

What is the greatest satisfaction in writing?

When people write, when it’s going well, you see the best arrangement of your ideas. The reason most writers find interviews painful, for example, is that speech is so shoddy compared to writing. You can rarely say what you mean and you say it in all kinds of messed up ways, grammatically. That can be good for writers, too, because they’re control freaks and sometimes it’s important not to have complete control over your utterances. But for me, the satisfaction of writing is getting down something I felt or a memory of something or a certain way I think about the world and having it sort of preserved and pinned down. Once that’s done, though, I have absolutely no urge to revisit it.

Zadie Smith will meet with students for an informal breakfast discussion of her work on Tuesday, March 27, in the Photonics Center Colloquium Room, 8 St. Mary’s St., from 9 to 10:15 am. Those interested in attending should register through Eventbrite here.

John O’Rourke can be reached at orourkej@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.